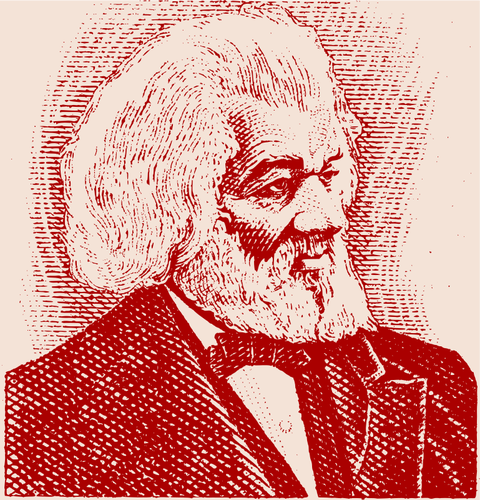

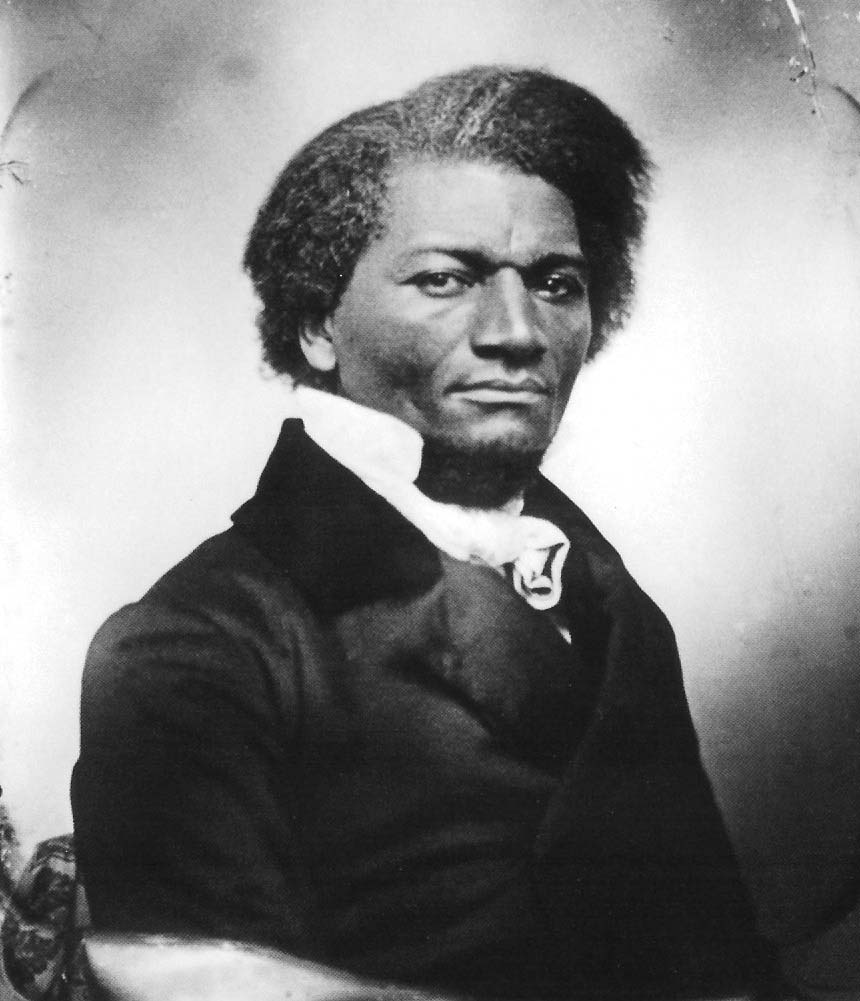

“Right is of no sex, truth is of no colour, God is the father of us all, and we are all Brethren.”

Frederick Douglass’ motto from his weekly publication the North Star.

On February 6th 1860, a “well known and popular advocate for the abolition of slavery” (Falkirk Herald, 1860) appeared before an audience in the Free Church on West Bridge Street, Falkirk.

Early Life

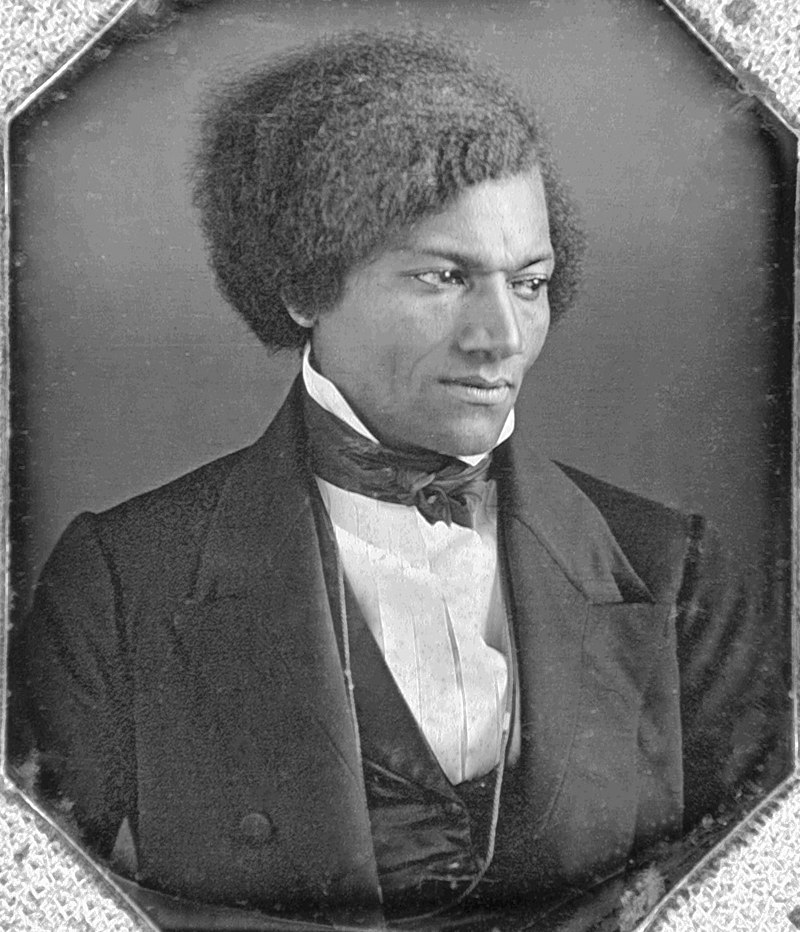

This advocate was Frederick Douglass, born into slavery as Frederick Augustus Washington Baily in 1817 or 1818 in Talbot Country, Maryland. At an early age, Douglass was separated from his mother, who was also enslaved. He was brought up by his Grandparents Betty and Isaac Baily. His father was believed to be “a white man, or nearly white” (Douglass, 1855) it was “whispered” that one of his “master’s” was his father (Douglass, 1855). At the tender age of seven Douglass was removed from the care of his grandparents and sent to live on the home plantation owned by Colonial governor Edward Lloyd, to live out his life enslaved.

Escape

Douglass made his successful escape from the horrors of slavery in 1838, by dressing as a sailor carrying the identification papers of a free black seaman. Douglass then made his way to New York where he sought protection in a safe house owned by abolitionist David Ruggels. He finally settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, with his new wife Anna, and changed his surname to Douglass. After escaping, Douglass was invited to tell his story of enslavement at abolitionist meetings. Consequently, he become a regular lecturer in the anti-slavery movement. Through the movement, he met William Lloyd Garrison, the founder of the abolitionist newspaper the Liberator. Garrison helped Douglass publish his autobiography, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, and advised him to “lie low abroad to avoid unwanted attention from [his] former owners” (Murray, 2015). Heeding this advice, Douglass undertook his first tour of Britain between 1846-1847.

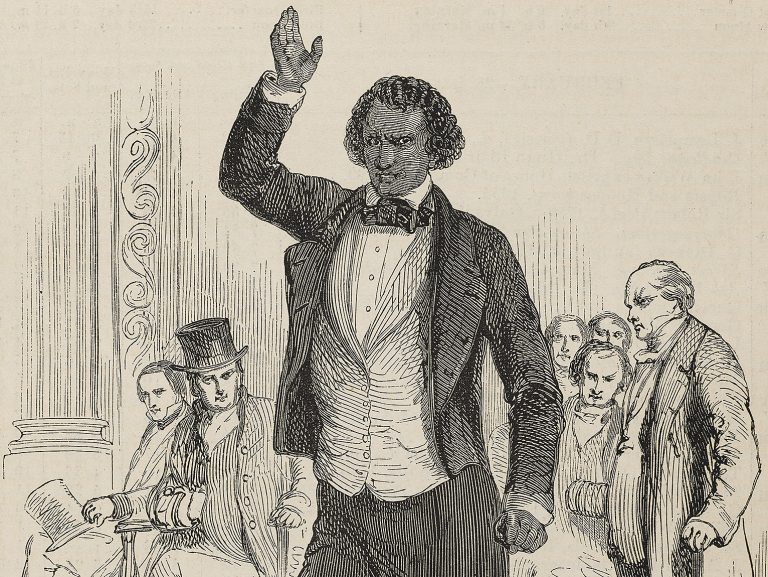

Douglass in Falkirk

The Falkirk Female Anti-Slavery Society invited Douglass to Falkirk during his second “mission tour on behalf of the case to which he is so zealously and earnestly devoted to” (Falkirk Herald, 1860). On the stage in the Free Church, Douglass was joined by several local figures including Mr Sheriff Robertson (the chairmen of the meeting), the Reverend James Muir of the South U.P. Church, Reverend James Mclean of Bank Street Chapel, John Wilson Esq. of South Bantaskine and Chas. Gould Esq, Banker. Seated within the body of the church were members of the Falkirk Anti-Slavery Association and several other local figures. After “an excellent and eloquent introductory speech” by the chairman, Douglass rose from his seat with a “great applause” (Falkirk Herald, 1860).

Douglass recounted to the audience that he was born into enslavement and lived 21 years of this life “in that degrading capacity” and “he had never enjoyed the benefits of a scholastic education” (Falkirk Herald, 1860). When enslaved, Douglass was not permitted to gain a formal education due to concerns that literate enslaved people could “forge passes or convince other slaves to revolt” (Sambol-Tosco, 2004). Around the age of 12, while enslaved on a plantation in Baltimore, the slaveholder’s wife taught Douglass the alphabet. The slaveholder, Hugh Auld, subsequently banned him from any further education. Despite this, Douglass continued to learn to read and write from the white children in the neighbourhood. As slaveholders and owners feared, Douglass was able to adopt an “ideological opposition to slavery” (Bibliography, 2020) through reading newspapers and seeking out political writings.

Explaining the System

The Falkirk Herald reported that Douglass provided a comparison between the slavery system in Brazil with the system in the Southern States of America. In Brazil, an enslaved person, “if enabled… could purchase his freedom in terms of the law of the country” (Falkirk Herald, 1860). Whereas, in America, an enslaved person could only purchase his freedom with the “consent of his master” - additionally, whatever little possessions or money an enslaved person had belonged to their master and could be taken at any time. Douglass highlighted there were 350,000 slaveholders, owning four million slaves who could be sold at markets “like cattle to the highest bidder” (Falkirk Herald, 1860). Douglass called for the “immediate abolition” of such an “atrocious and debasing system” (Falkirk Herald, 1860). Douglass provided a further comparison of the system to that of a highway robber demanding “Your money or your life” from unfortunate travellers; to a slaveholder demanding “Your labour or your life” from enslaved people.

Once Douglass had completed his comparisons he moved onto the principles of the slavery system. This principle of slavery he believed was to weaken the “chief purpose of man’s creation, was contrary to divine law and abhorrent to the best feelings of humanity” (Falkirk Herald, 1860). Further to this he discussed the work which had been undertaken to put an end to this system in the previous 15 years by abolitionists, and the work still to be done to end this abhorrent system.

Ways to Help

Fredrick Douglass received a payment of £5 (around £295 today) from the Falkirk Female Anti-Slavery Society for his “excellent lecture” (Falkirk Herald, 1860). The society additionally voted to give Douglass and further £5 for clothing for fugitives who had “escaped from slavery” (Falkirk Herald, 1860). This was in response to Douglass’ closing remarks on assistance Anti-Slavery Associations could provide to those who had escaped.

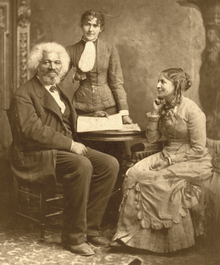

Across his two tours of Britain and Ireland between 1846-47 and 1859-60, Douglass delivered hundreds of “impassioned” (National Library of Scotland, Unknown) public lectures. Due to popular demand, he repeatedly gave speeches in major cities across Scotland including Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Aberdeen, plus towns and villages including Falkirk, Perth, Dundee, Kelso, Montrose, and Dalkeith.

End the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Haiti became the first country to abolish slavery in 1804, following the Haitian Revolution, the most successful revolution of enslaved people which led to Haitian independence from their French colonisers. The British 1807 Slave Trade Act banned the trading of enslaved people, however this continued illegally. The Slavery Abolition Act passed in 1833 and came into effect in most British colonies in 1834. But it wasn’t until the thirteenth amendment of 1865 that slavery was abolished in the USA.

By Lorna Keddie, Hidden Heritage Online: Industry and Empire volunteer 2020.