Delve into the history of one of the lost distilleries which one stood on the Forth and Clyde Canal and which exported whisky all over the world…

Uisge Beatha, the Water of Life, or Whisky, has been distilled, matured and enjoyed across Scotland for over 500 years.

The distillation of whisky has “officially” taken place in Falkirk since the 1790s and presumably “unofficially” for many years before that.

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

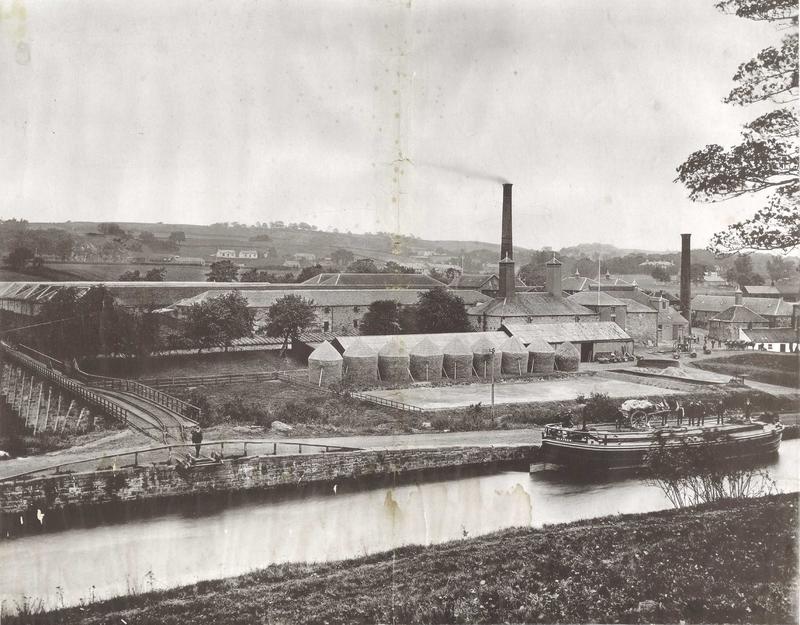

Initially a corn mill on the banks of the Forth and Clyde Canal, Bankier was converted into a malt whisky distillery in 1828 by Daniel MacFarlane. During the late-1830s the distillery began trading as the Bankier Distillery Company and kept this name until its closure in 1928. Bankier was one of six distilleries situated on the banks of the Forth and Clyde Canal. The others include Rosebank in Falkirk (which you can read about here), Port Dundas and Dundashill in Glasgow. The proximity to the Canal would have allowed the landing of raw materials onto a connecting wharf and tramway including barley from Aberdeen and Forfarshire, and coal.

Risk and Contamination

In 1897 the Distillery and Company were acquired by James Risk. During Risk's ownership, the distillery was visited by Alfred Barnard, during his tour of “The Whisky Distilleries of the United Kingdom.” Barnard described Bankier as a “busy scene” with the “appearance of a country Distillery” covering six acres of land near Denny. The buildings were made of stone, with the majority of production buildings including two Maltings; two Kilns and Malt Stores; Barley Stores; Marsh and Still Houses situated on the lower ground towards the Forth and Clyde Canal. Built uphill from the production buildings sat seven Bonded Warehouses with the capacity of storing 4,500 casks. In 1885 Bankier produced 150,000 gallons of a “pronounced and excellent Highland style of Whisky” (Barnard 1887 320) with the capacity to increase to 180,000 gallons if a sudden surge in demand occurred.

The water used in the distilling process and to power the distillery – in the days before electricity – would have come from the Doups stream. This water was said to be “pure and soft... fit for... the distillation of whisky” (Scottish Court of Session 1892). However, in the latter years of the James Risk ownership, the distillery had issues with its water supply when the Doups stream became contaminated with wastewater from one of the many mines in Banknock. The addition of the wastewater changed the chemical make-up thus, making the water “less suitable” for distilling.

In 1892 The Bankier Distillery Company took John Young & Company to court to gain an order to prevent John Young & Company pumping wastewater from their mine into the Doups stream. Additionally, The Bankier Distillery Company pursued damages to the value of £250 (around £22,000 today) to cover the costs of repairing the damage to distilling equipment. The case was settled when John Young and Company were restrained from pumping wastewater into the Doups stream and ordered to pay The Bankier Distillery Company £25 (£2,200) in damages. The Bankier Distillery Company returned to court again in October 1899, looking to transfer the restrictions placed on John Young & Company to Young’s Collieries Limited. Unfortunately, the court refused to transfer the restrictions as Young’s Collieries Limited had nothing to do with the original complaint in 1892. In Scots Law, the transfer of restrictions could only be placed on a person or company who had infringed or jeopardised rights that had been protected. This was not the case which is why restrictions could not be placed on Young Collieries Limited.

Empire and War: James Buchanan & Co. Ltd.

After the turn of the century in 1903, Bankier Distillery and Company were acquired by one of the giants of the industry – James Buchanan & Company Limited.

The acquisition of the distillery was as part of Buchanan’s plans to control the production of whisky from grain to glass.

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

The whisky produced by Bankier during this era would have been used in the blends produced by Buchanan, including the famous Buchanan’s Black and White Scotch Whisky. This blended whisky is famously represented by a black “Scottie” dog and a white “Westie” dog. Buchanan’s drew on the “black and white” theme in other ways. For example, an advert from the early 1900s showed a “white” woman walking in front of a “black” woman, hinting at a “colonial mistress and maid relationship” (Hands 2018 79), then considered natural, now rather problematic . The concept of the “black and white” theme ties in with the ideology of British Imperialism – with the opposing palette symbolising a contrasting yet harmonic relationship – implicitly similar to a good blended whisky (Hands 2018 78). The blends produced by Buchanan were exported all over the world to Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa, the Caribbean, North and Latin America, and the Far East, where Buchanan & Co. was appointed as the whisky supplier for the Emperor of Japan in 1907. The whisky was also used in the famous White Label blend produced by John Dewar & Sons.

When the nation entered its third year of fighting during World War One in 1917, Bankier distillery was forced to shut down production entirely; due to a Government ban on distilling in whisky distilleries that used Pot Stills (which Bankier did) or did not produce yeast as a by-product. This ban forced many small and independent distilleries out of business. It was during this period that James Buchanan & Company Limited merged with John Dewar & Sons, creating Buchanan-Dewar Limited. The merger allowed both companies to pull resources together and survive the wartime restrictions on distilling and trading of whisky and competition from other distilling firms.

The Lost Distillery

The final owner of Bankier Distillery was the Distillers Company Limited (DCL) who acquired the distillery in 1925 through a merger with Buchanan-Dewar Limited. The DCL spent most of the 1920s purchasing and closing down distilleries across Scotland to ensure the industries survival in the aftermath of World War One. It was with this in mind that Bankier Distillery produced its last drop of whisky in 1928, with its closure being accredited to the elevated cost of whisky due to high duties. All was not lost as the distilleries Maltings and Warehouses were still in use until the early 1970 and late 1980s, respectively.

The “handsome” stone buildings were finally demolished by the early 1990s. However, some remains of the Bankier Distillery can still be seen today, these include part of one of the Bonded Warehouses and a rusting gate post.

By Lorna Keddie, Great Place volunteer, Hidden Heritage: Industry and Empire project 2020.