Enjoy the story of Sir John de Graeme’s tomb, which has undergone significant changes over time, and his role as William Wallace’s right-hand man.

The Tomb

For many years now, the Battle of Falkirk has held a special place in Falkirk’s collective memory, owing much to the efforts of local history societies. Each July, an organized gathering takes place in the town centre to pay homage to this infamous battle in the lengthy struggle for Scottish independence, in which English forces defeated the Scots, who were led by William Wallace.

One of the most noteworthy casualties from this battle was John de Graeme of Dundaff, Commander William Wallace’s right hand. de Graeme had helped lead the Scots to victory at Stirling Bridge, but at Falkirk he was fatally struck from behind through a gap in his armour; it is said that Wallace himself carried the body of his fallen brother in his arms for burial in the nearby Falkirk churchyard, now Falkirk Trinity Church, vowing to avenge his death (Williams).

Today, de Graeme’s tomb assumes a pivotal role within the annual commemoration activities, wherein people gather, some in period costume, to pay homage to this fallen knight by laying wreaths at the foot of the monument.

A Brief Timeline of the Monument

In the centuries since his death, Sir John de Graeme has garnered the illustrious legacy of Falkirk’s own medieval hero, with his final resting site becoming a unique place of pilgrimage for Scots and internationals alike.

Some might say the tomb’s visit by celebrated bard Robert Burns in the late eighteenth century, during his stay in Falkirk, marked the first in a series of events that drew public attention to the figure of John de Graeme, and his national significance. According to an article from the Falkirk Herald in 1903, when asked about his visit to the area, Burns allegedly replied, “Falkirk - nothing remarkable, except the tomb of Sir John de Graeme” (“Burns Anniversary: Falkirk Burns Club”). The convergence of these two Scottish icons was even considered momentous enough to elicit its own inscription on the monument many years later:

“This morning I knelt at the tomb of Sir John the Graham the Gallant friend of the immortal Wallace. – Robert Burns 26th August 1787.”

Despite this high profile visit, extensive renovations of the tomb did not commence until the mid-nineteenth century, coalescing with the conservation movement that had gained traction in the Victorian era (Jones, 185). Renovations of the tomb took place at the behest of the Sir John de Graeme Lodge of Oddfellows which had been formed in 1841 (“The Tomb of Sir John de Graeme: The Procession”). Societies such as this were designed with the aim of providing charitable activities to the community prior to the advent of the Welfare State (Gillon).

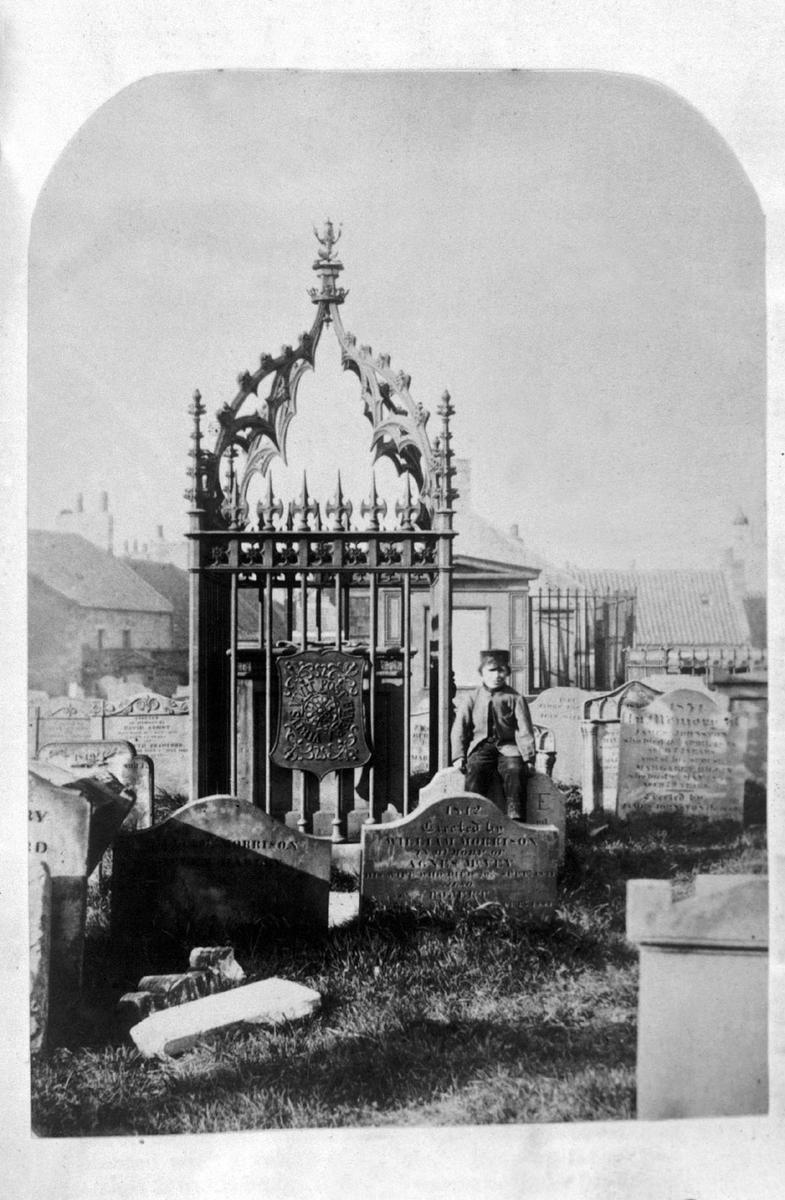

In 1860, the Oddfellows contracted Falkirk Ironworks to fully renovate de Graeme’s tomb in the Gothic style. Having raised the funding through public subscription, the tomb was to be fully enclosed with a stylized cast-iron railing and cupola surmounted by a gilded coronet and Scottish Lion (“The Tomb of Sir John de Graeme: The Procession”). Adding to the spectacle, a bronze replica of the two-handed sword alleged to have been wielded by de Graeme was fixed over the tomb in 1869 (“Visit of the British Archaeological Association To Falkirk”).

In the 1960s, the landscape of the graveyard was vastly altered, drawing further attention to this magnificent monument. A great deal of the cemetery’s memorials and tombs were removed and reburied in the nearby Camelon cemetery (The Society of John de Graeme), “leaving only a handful of memorials of historical significance” (“Falkirk Town Centre 1”). As a result, the space surrounding the main tomb has been further incorporated into the monument we see today, with various plaques and inscriptions.

As one might expect, the monument has not been immune to the trials of time or the occasional act of mischief. Though the iron railing has done much to protect the tomb’s distinct architectural features, large pieces of scroll work have been knocked from their place on the flat stone (“The Tomb of Sir. John de Graeme – Disgraceful Vandalism”), and throughout the years vandals have stolen de Graeme’s replica sword (Williams). Despite this, there remains a continued and vigilant effort to maintain the monument; and, most recently the Society of John de Graeme has requested that custodianship of the tomb be transferred into their hands (Reid).

Authenticity & Sites of Memory

As previously discussed, de Graeme’s tomb has become the central feature within the annual remembrance of the Battle of Falkirk. One might suggest that this is owing to a sense of authenticity attributed to the tomb. While the actual site of the Battle remains somewhat contested, de Graeme’s tomb serves as a direct link to history as one of the only knights from that era whose final resting place has been confirmed by historians (Williams). Perhaps solidifying this notion, the grave was opened in 1927 in order to build foundation pillars to support the combined weight of the tomb’s flat stones, heavy iron cupola and railings which had sunk considerably into the earth (“The Second Battle of Falkirk, 1746”). Coming across the tomb’s remains, the Falkirk Herald reported:

“Embedded in solid clay and about six feet from the surface were found what a local medical authority presumed to be the bones of the great warrior. There were no signs of a coffin, and from the nature of the soil, imperfect as the remains were, it seemed probable from the day on which the first battle of Falkirk was fought, in the year 1293, that the ground had never been disturbed. The thigh bones of the hero were still in perfect form; these measured seventeen inches in length and were above the average strength. The only remains of the skull was the impression on the clay. Needless to say, the remains were carefully deposited in the spot from which they had of necessity been removed. The late Mr Stewart M Watters, who was one of the leading spirits in renovating the monument, was present at the opening of the grave, and gave it as his opinion “that as the remains of only one person were found, and these seemingly never having been previously disturbed, they must have been those of Sir John de Graeme’” (“The Second Battle of Falkirk, 1746”).

John de Graeme’s Legacy

Some might argue that the preservation efforts and commemorative function of de Graeme’s tomb represents much more than the continued shared reverence for history. Over the years, de Graeme as an individual has become heavily associated with notions of heroism, bravery, and self-sacrifice in service of nation. Indeed, the renovation of the tomb as well as the erection of the National Wallace Memorial occurred during a time in which the modern Scottish Nationalist Movement was just beginning to plant its roots (Morgan, 376). It is therefore unsurprising that the memory of William Wallace, and John de Graeme by association, has oftentimes been wielded throughout history in discussions surrounding Scottish self-government (“Scottish Self-Government: Celebration of Battle of Falkirk Anniversary”).

Scholar Laurajane Smith has suggested that heritage is something that communities actively construct in the present, “in response to cultural, social and economic needs and aspirations” (Smith, 239). With this in mind, the massive changes undergone by de Graeme’s tomb can be taken as evidence that de Graeme’s cause continues to resonate in the hearts and minds of the community.

By Paige Foley, Great Place Digital Heritage Placement 2020. Hidden Heritage Online: Statues and Monuments project.