This story explores the relationship between James Bruce esquire (1730-1794), of Kinnaird, and the Carron Company.

Travel Funds

The some twelve years traveller James Bruce spent on his adventures abroad, on which his international reputation are based, were dependent on certain important factors. Alongside a desire to prove himself to his peers, he was multi-lingual and had an explorer’s attitude to ideas about scientific discovery. Fortunately for him, he was able to fund his sense of adventure and interest in other cultures. This was largely due to Carron Company having opened in 1759, an iron foundry adjacent to his family land, which paid him to mine its coal. Bruce’s opportunity to exercise his desire for discovery was enabled by the funds from the Carron Company.

A study of some aspects of the relationship between Carron Co. and James Bruce offers an insight into the consequences of the arrival of the Industrial Revolution in Scotland. James Bruce made the most of this chance arrival of a source of funds. It is worth noting that James Bruce received no public honours for his cultural and geographical discoveries in Abyssinia (now Ethiopia), his only public recognition came from the publication of his adventures in his lifetime.

The account of his travel experiences was criticised as exaggerated by his contemporaries perhaps they were envious, perhaps they found the work more revealing than was then the fashion. But time has shown that his accounts are mostly accurate. Time has not obscured his achievements. Bruce provides an exceptional example of innovative thinking, combined with a determination to overcome all obstacles. His strength of character often got him into trouble, yet the application of his wits in a charming manner helped save his life on many occasions. It is Bruce’s relationship with Carron Co., however, which is the subject of this story.

Cultural Influences

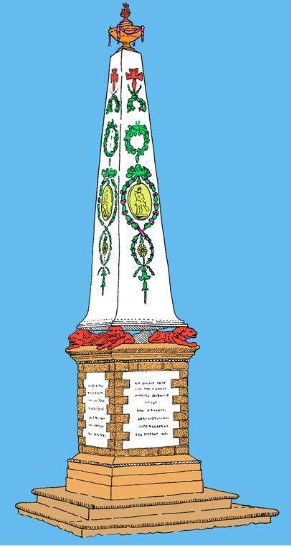

Geoff Bailey, of Falkirk Museum, has uncovered another attractive aspect of the obelisk – “it was brightly painted.” It was, with two other local later iron grave monuments, “a tribute to the engineering skills of the manufacturers – and therefore a source of wonderment to one and all!”

The exotic Eastern cultural influence on Bruce is not without evidence. On his travels in Abyssinia, Bruce made many discoveries, one of which was their fantastic grave memorials: tall, hollow, stone-built square “Stelae” towers with a door at the base, similar to Egyptian obelisks. Bruce’s tower is influenced by, yet different from to the Abyssinian and Egyptian styles; more decorative than either.

It is formed of two parts joined by well sculpted lions posted at each corner (a rare early example of the skills of the pattern-makers and moulders). The upper part is topped with a classical everlasting lamp, and set with elaborate plaques, symbolic depictions of classical Greece, and a representation of, at that time legendary animal, an elephant. The four lions guard the tower. On the lower base plinth are the words cut from iron plate to identify Mary and James along with other family members.

Having considered the emotional significance of the Bruce monument – a Falkirk version of the more famous love memorial the Taj Mahal – it is also worth considering why it was made of iron, and the relationship that James Bruce had with the Carron Company.

Iron

The founders of Carron Company were part of the wide-ranging Enlightenment movement of new ideas, inspired by a renewed interest in science and philosophy. The three founders of Carron Co. aimed to put science to use for making useful things profitably. There are many reasons behind how and why they ended up establishing a foundry on the banks of the River Carron, but this undoubtedly had profound consequences on the area and its population. Many, like James Bruce, seized the opportunity to explore their own potential and make a significant contribution to the Industrial Revolution.

The Bruce family were fortunate to have coal assets that the Carron Company required. So began a lifelong association between James Bruce and Carron Co., not always harmonious yet always productive. Bruce held Carron Co. to the letter of their contracts, often taking legal action to enforce his rights. Yet without their contribution, Bruce could not have been such an explorer.

It is not surprising, then, that James Bruce used iron in a new manner. It had provided the essential ingredient in transforming his life, why should iron not be the medium for commemorating his wife? In the 1770s, because of technical innovation, iron was the now an easily available metal, both for supplying basic needs (pots, pans and tools), and shaping a revolutionary change in how things were made. Carron Co.’s closest competitor, the Darby foundry in Coalbrookdale, and the source of its first skilled workers, had in 1779 just completed the Iron Bridge – the first bridge made of cast iron, and a technical wonder. Bruce’s iron tower was an opportunity for Carron Co. to show that it could also put iron to innovative use.

The other best-known iron grave memorial tower was an iron coffin made for John Wilkinson, the inventor of the boring machine, which allowed the Carronade and James Watt’s steam engine cylinder to be safer and more efficient. Embedded in the Carron Co. clock tower is a remnant of an early steam cylinder made for James Watt, at Carron works, whilst he worked at nearby Kinneil. Finally, it is worth connecting Bruce’s tower and other Carron Co. made iron towers, which would become some of the world’s best known mediums of communication – the Post Office letter box, and the public pay phone kiosk first made at Carron works in 1927.

This summary consideration of the relationship between James Bruce and the Carron Company will, I hope encourage further interest in the cultural legacy of Carron Company, the iron history of the Falkirk area, and the national and international significance of an area which could be described as the iron heart of Scotland.

Although James Bruce lived a dangerous and adventurous life abroad and in Scotland, he died from injuries after a simple fall at home, and was interred under his iron Taj Mahal. Uncovering Bruce’s story provides a cast iron example of the possible excitement in discovering new ideas, places and people in and beyond Falkirk.

By Dr. Duncan Comrie, Falkirk Made Friend, 2020.