Find out about the turbulent history of the Roman fort at Castlecary.

The Roman Fort at Castlecary was a defensive site with a tumulutous history, as a result of the difficulty the Romans faced in holding what they called Caledonia, and the numerous decisions to abandon Scotland and return the frontier to Hadrian’s Wall. The first recorded excavation of the site was in 1902. Interest in Castlecary’s Roman military presence and its excavation was recorded in the 29th of April 1903 edition of the Falkirk Herald, with several further excavations occurring in the mid and later twentieth century.

Early Construction

The first Roman fort built at the site of Castlecary was constructed between 80 and 90CE by Gnaeus Julius Agricola (above), who fought in both England and Wales before attempting a conquest of Scotland (Canmore). Originally from Southern Gaul, Agricola was Governor of Britain from 77-85CE, first arriving a year after being granted the role (Beard p.521). According to the admittedly biased Tacitus, who wrote favourably of his father in law, Agricola was given command of the Twentieth Legion and set off for Scotland, exterminating a whole tribe upon his arrival (Tacitus). By 83CE, Agricola had built a legionary camp at Inchtutthill on the River Tay and defeated the Highland locals led by Calgacus at Mons Graupius (the location of this site is still subject to debate), effectively securing the region for Roman fortifications (Le Glay, Voison and le Bohec p.308).

Agricola’s fort at Castlecary was probably occupied between 82-83CE (Canmore) and possibly saw action during the revolt of the Caledonians during his sixth year in Britain. Tacitus mentions attempted attacks on fortresses but does not specify place names (Tacitus). Excavations of first century pottery proves Agricola’s forces occupied Castlecary, but his original fort and its defences have not been located (Canmore). After a few years, the Romans legion and auxiliary units were ordered out of the Falkirk area, and Scotland as a whole, due to events in the wider empire, with a war in Dacia (modern day Romania and its neighbouring countries) taking priority. As a result of switching military attentions to Dacia and the removal of 5,000 men from Scotland (or, if Tacitus can be believed, Emperor Domitian’s fear over Agricola’s extensive skills as a commander), Agricola was recalled. Castlecary was abandoned while Roman forces returned to Hadrian’s Wall (Canmore).

The Antonine Wall

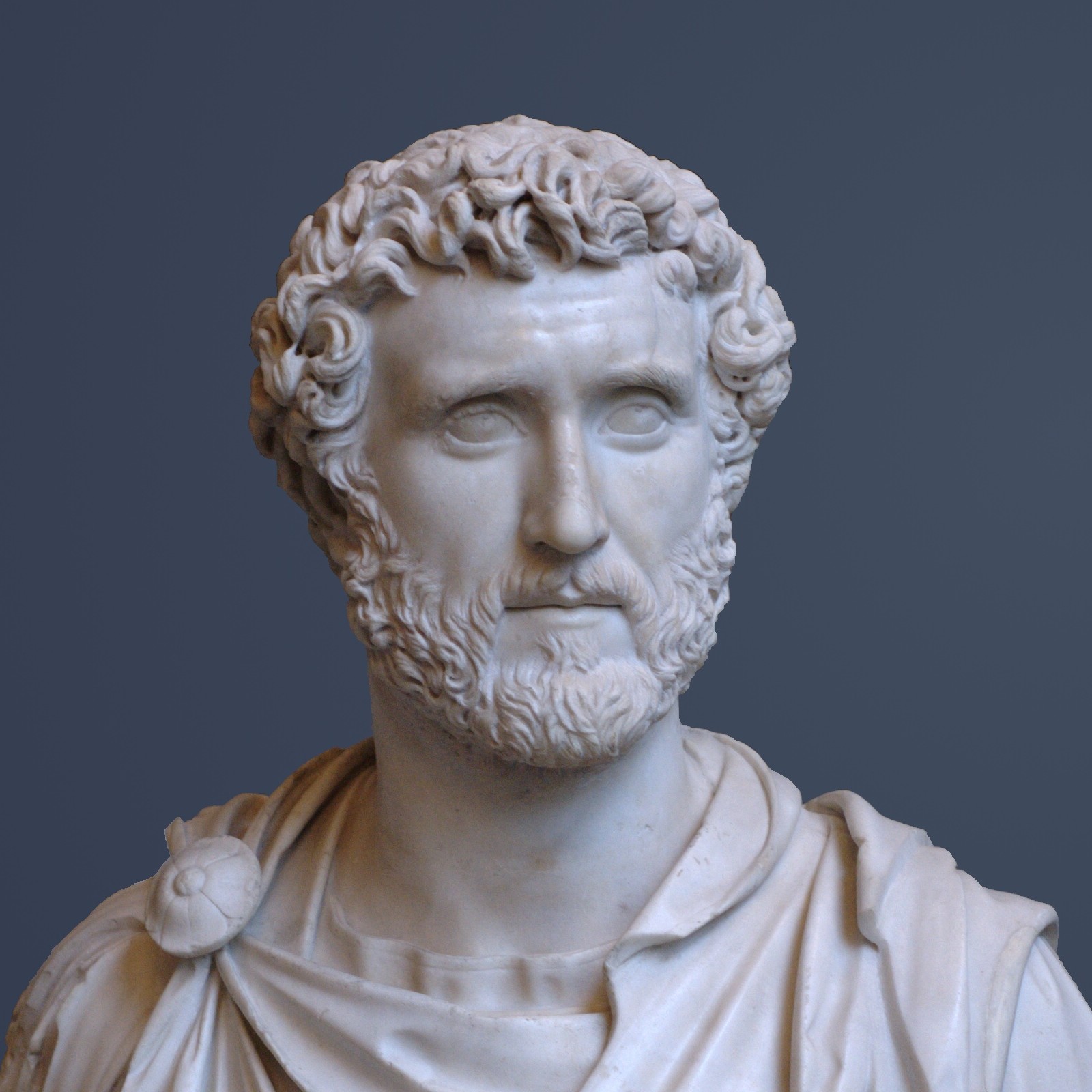

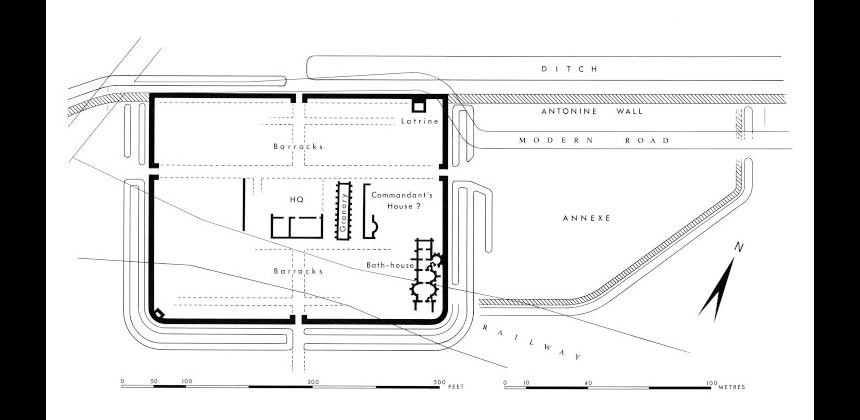

The fort was occupied once again around eighty years later during the reign and invasion of Antoninus Pius (above). It became one of a series of forts and fortlets on the Antonine Wall, of which only two, including Castlecary, were made of stone. The new fort contained a headquarters, bath house, commandants house and granary, alongside a latrine pit, drainage system and an eastern annex, also fortified (see fig. 3). The fort is also believed to have contained several workshops and was defended by stone walls on several sides with several ditches (Canmore).

As a fort that was part of the Antonine Wall, Castlecary became part of the Roman frontier defence system at the most northerly boundary of the Roman empire (Le Glay et al p.379). In addition to the wall and forts, the Antonine wall had watchtowers and outposts that reached up to 80km from the wall, which included camps and forts such as Ardoch in Braco, and Camelon (Le Glay et al p.379). These were all connected through communication systems such as smoke and torches, which were used to communicate to and from the wall, as well as across it. The defences also included guard posts, auxiliary forts, and legionnaire camps behind the lines, and were crucially connected by the Roman road network, which allowed for the movement of goods and troops (Le Glay et al p.380). In addition to these military constructions, the Romans also made use of diplomatic missions, trade, and the tactical use of the surrounding rivers and hills to make their new northern frontier in Scotland defensible (Le Glay et al p.380).

The Second Fort

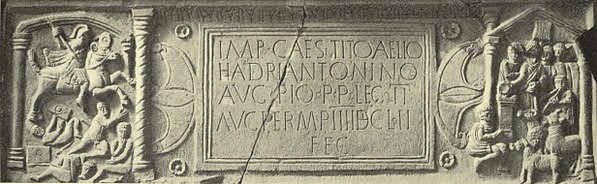

The second fort at Castlecary was built by the Second Legion and Sixth Legion Victrix, who dedicated an inscription to the Roman goddess Fortuna whilst at the site (“Legions and auxiliary units”). They were assisted in building the fort by the First Cohort of Tungrians, a Belgian Auxiliary unit who were also present at Crammond, and garrisoned both the forts. Other Auxiliary Units known to have been present at Castlecary include some of the First Cohort of Vardullions, recruited in Spain, and the First Cohort of Batavians, who would have helped build and garrison the fort once it was established (Canmore).

After the Romans

In its later years, Castlecary witnessed conflict between 155-156CE during the northern British revolts. But the fort, and the whole Antonine Wall, were eventually abandoned after the death of Antonius Pius in 160CE, and the Romans returned to Hadrian’s Wall which became the frontier once again (Canmore). Despite another attempt by Emperor Septimius Severus to conquer Scotland in 208CE, the Hadrian’s Wall border was again preferred by his son, the Emperor Caracalla, whom made peace with the Caledonians (Le Glay et al p.423). Today, only some stone and part of the Eastern rampart from the second fort can be seen (Canmore).

In addition to Castlecary’s ancient history, its location remains of interest in both medieval and modern history. It was at this site that Edward I called his forces in 1304 to lay siege to the Scots. The fort’s 17th century tower was burned by the Jacobites in the 1715 rebellion, and in the 19th century a railway was built directly over the site, significantly damaging the fort’s remains (Canmore).

By Laura McWhinnie, Hidden Heritage Online: Ancient Falkirk volunteer.