Find out the history behind an ancient artefact unearthed along the Antonine Wall and rediscovered recently.

Discovering the Urn

When we think of discovering precious Roman artefacts, the mind is likely to conjure images of an archaeological team in the field, trowels in hand, tediously scouring the earth for evidence of times gone by. Recently, however, a magnificent piece of history regarding the Roman Empire’s northern frontier has been rediscovered within the collections at National Museums Scotland – a funerary urn of exotic provenance.

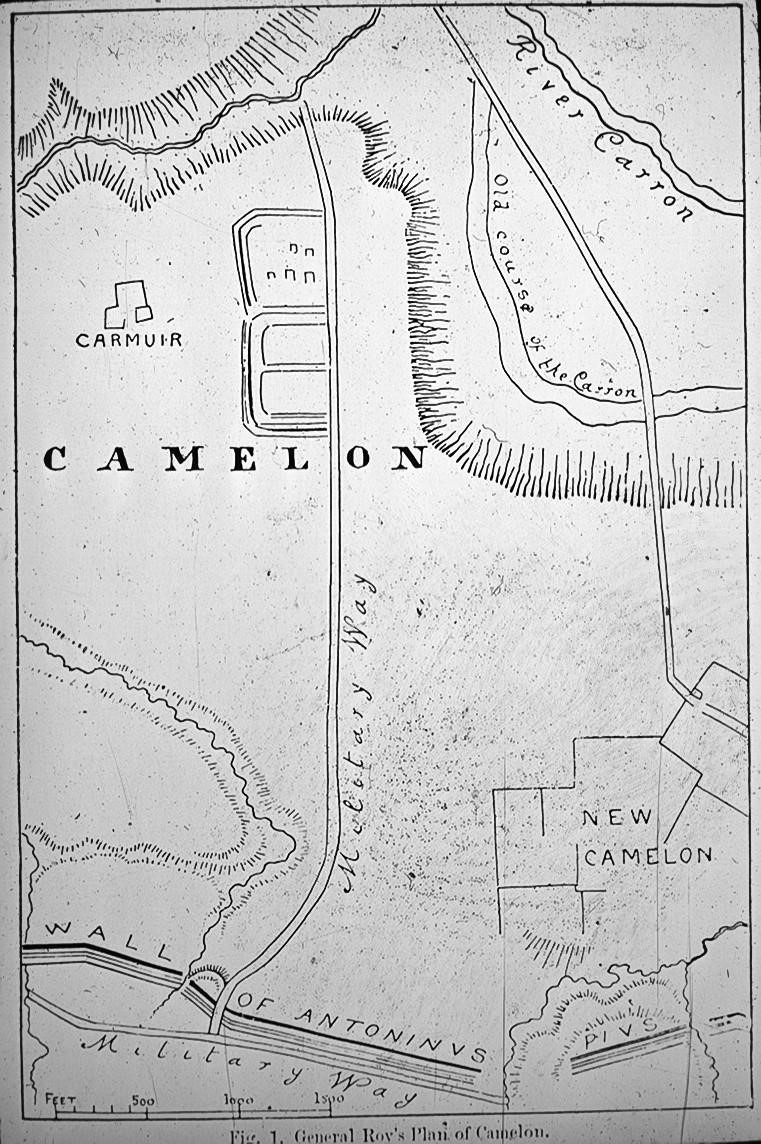

The urn was initially discovered in 1849 during the construction of a railway line in Camelon, which ultimately revealed a variety of treasures of Roman origin. Details of the urn first became public in an 1850 issue of the Stirling Observer:

“So late as July 1849, great quantities of relicts of antiquity were found by the workmen at the Midland Railway, among which was a very fine alabaster urn, containing a quantity of calcined bones. Unfortunately the urn was broken, and fragments fell into different hands” (Hunter 235-236).

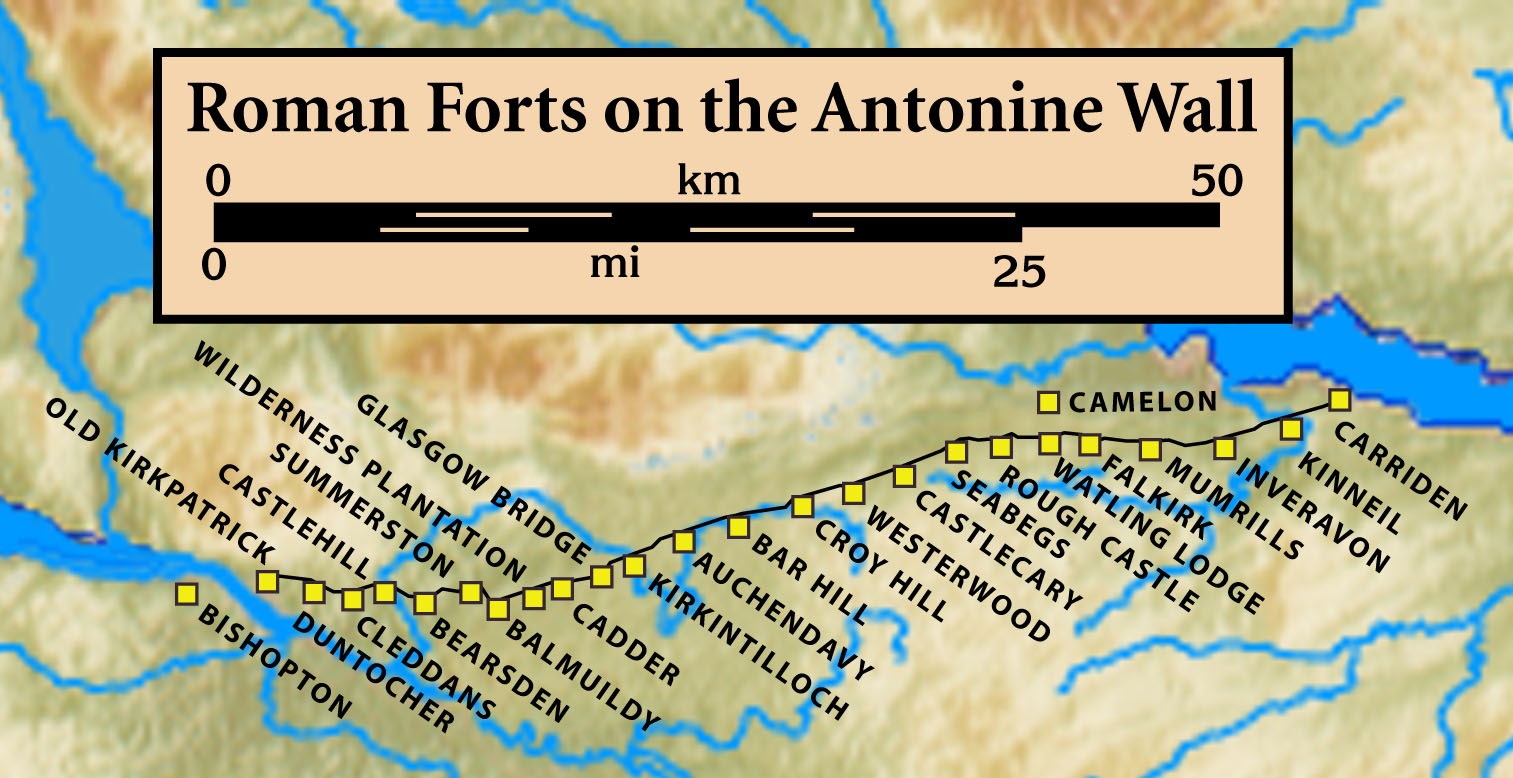

The urn was discovered in Camelon, just north of the Antonine Wall. Facing the unconquered northern tribes, Camelon is thought to have been one of the most important forts along the Roman Empire’s north-western frontier. Below you can see an 1899 photograph of excavations at the Roman fort in Camelon.

Display, Obscurity, Rediscovery

Soon after its discovery, the two largest fragments of the urn were put on display at the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, as well as the National Museum, generating a great deal of excitement in the academic world as well as among the greater public. Unfortunately, this interest was short lived. On further examination of the urn, Joseph Anderson, Scottish antiquarian and keeper of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland at the time, dismissed the significance of the urn in a simple footnote:

“The alabaster vase is now in the Museum, but presents no features which suggest Roman workmanship.” (Hunter 237)

And so, with its provenance and authenticity in question, the urn was relegated to the collections shelves where it remained obscured for the next century.

Until, rather serendipitously, it was rediscovered by Dr. Fraser Hunter, Principal Curator of Iron Age and Roman Collections for National Museums Scotland (NMS). Just as the NMS collections were moving premises from Leith to Granton, Hunter stumbled upon an item like none he’d seen before. Upon further examination, he found that the artefact had been incorrectly identified as alabaster when it appeared instead to be travertine – a stone derived from Egypt (Hunter, “Egyptian luxury in Roman Scotland”).

Travertine

While Roman pottery sourced from Egyptian stone is not a wholly uncommon archaeological find, the Camelon urn represents just one of three travertine urns that have been found beyond the Mediterranean frontiers of the Roman Empire. So how did this artefact end up so far away from home?

The revelation that the urn was not made of alabaster but rather Egyptian travertine is significant for several reasons. Around the middle of the first century, items carved from Egyptian stone grew in popularity in Rome. Though easy to carve, travertine was also a particularly delicate and brittle material, and therefore costly to acquire – reserved for only the wealthiest of men. However, the stone was not only highly sought out for its perceived value and exclusivity, but also as a result of the growing admiration held by the Romans for the funerary practices and beliefs of Ancient Egypt. This yellow-hued stone was increasingly utilized in death and burial practices in Ancient Egypt due to its supposed purity and cleanliness, as well as the widely held belief that the stone had the power to regenerate life (Perna 78).

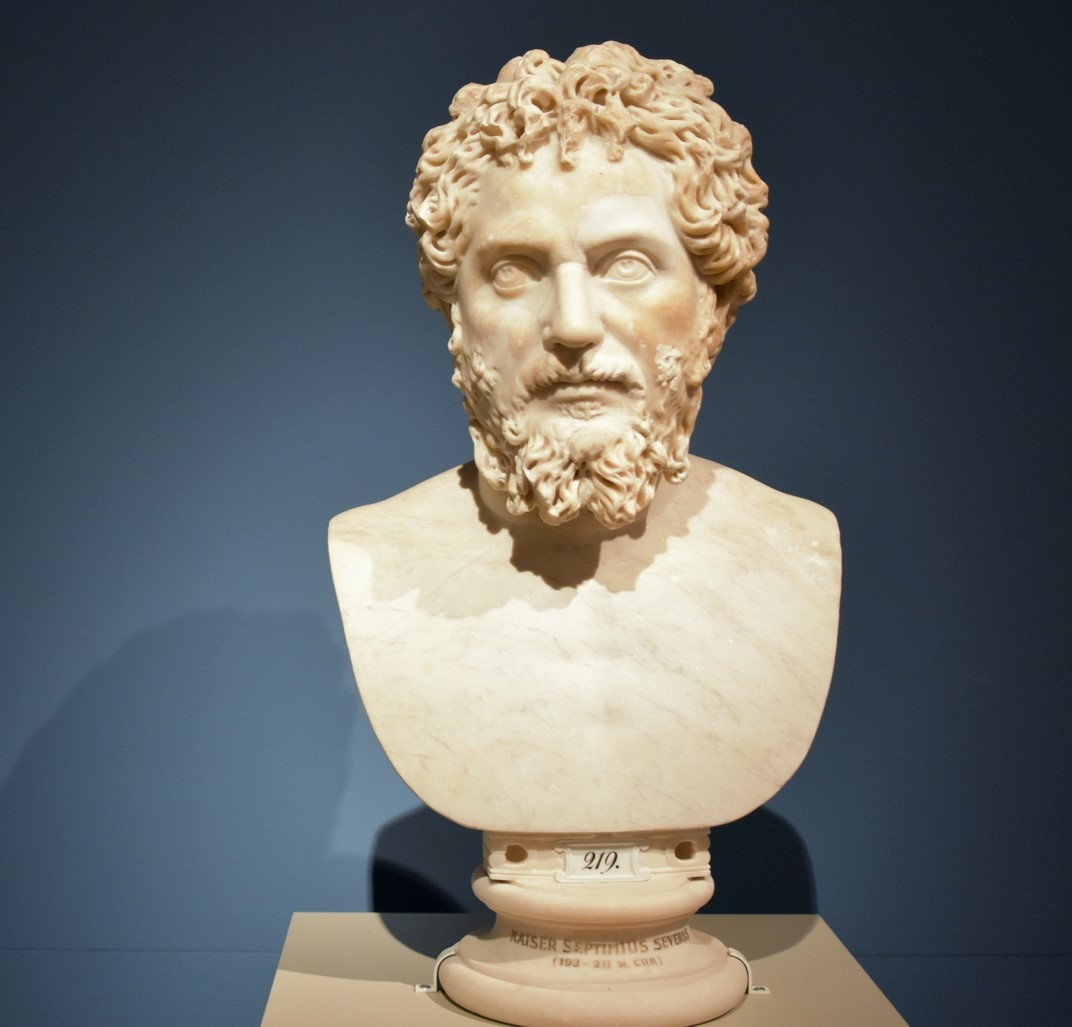

The distant origin of such an item is a clear indication that the urn’s former occupant was from the most elite social strata. Scholars are confident that, before his death, the previous occupant was brought to the Roman Empire’s northern frontier on a military campaign, urn in hand; much like the emperor Septimius Severus, who was known to have brought his own urn to Britain on a military campaign, with explicit instructions for the urn to be sent back to Rome following his death (Hunter 241). Here we can see the bust of Emperor Septimius Severus. Following his death in 211 AD, his remains were placed in an urn of alabaster stone and brought back to Rome from Eboracum (present-day York).

Burial Practises

The Camelon urn ultimately represents an incredible piece of the puzzle that is Ancient Falkirk. While there is significant material culture relating to burial rituals and funerary rights in mainland Europe, very few Roman burials have been documented within Scotland (Collard and Hunter 525). While Roman tombstones have been found along the Antonine Wall, most notably at Shirva (“Key Artefacts” Antonine wall), little evidence exists of the culture surrounding death and burial in Roman Scotland. Congruent with Roman law, it was forbidden to bury the dead within Roman settlements, and as such cemeteries were oftentimes located at a distance from the fort (Breeze 81). And, until recently, the archaeological focus within Scotland has focused primarily on excavating the forts themselves, rather than the surrounding areas (“Bodyguards, corpses, and cults”).

With little to go on – the precise location in which the urn was found, and the lack of other surviving contextual artefacts – scholars have struggled to date the Camelon urn thus far. While it is clear now that the urn dates to a time in which the Romans occupied the fort at Camelon, there were two separate and distinct periods in which the fort was occupied – the Flavian phase (circa 79-86 AD) and the Antonine phase (circa 140 – 158 AD) (Hunter 240-241).

The rediscovery of this artefact ultimately invites more questions than answers, it would seem. Based on the historical records of the urn’s initial discovery, it is clear that there were not only additional pieces of the urn, but also that it was found to have held calcined remains. The questions, then, are – where are they? Were they simply discarded in favour of elements thought to hold more value? Were they taken as a “souvenir” of a time long gone? Did they stumble into the personal collection of a local history buff?

Finally, and perhaps more broadly, with the notion that this precious piece of history had, until only recently, sat untouched within a museum collection for over a century, one is also tempted to ask – just how many other treasures are out there, hidden in collections across Scotland, awaiting a fresh set of eyes to realize their significance?

Perhaps, in time, our questions will be answered.

By Paige Foley, Hidden Heritage Online: Ancient Falkirk volunteer and Great Place Digital Heritage Placement.