Find out about Roman dogs and the mysterious paw print of the Antonine Wall!

From Italy to Falkirk

When I started to study Roman Archaeology at the university of Padua, in the north-east of Italy, almost twenty years ago, I never thought that I would end up living at the very northern frontier of the Roman Empire, but here I am. When I moved to Falkirk seven years ago and decided to volunteer at Callendar House, I was keen to learn as much as possible of the local history, particularly the Roman period and the Antonine Wall. I spent many days cataloguing and studying ancient artefacts with Geoff Bailey, the Keeper of Archaeology and Local History, and also took part to several of his digs. The aspect of the everyday life and the psychology that stands behind most of the ancient artefacts is the engine that pushed me to investigate more, to know more about how these people, who were here in this area 2,000 years before us, lived and interacted with the world around them.

The Paw Print

People from the past have left us massive fortifications and sculptures like the Bridgeness Distance Stone, but also more ordinary objects like a tile imprinted with a dog’s paw print. The artefact was found at Rough Castle and is now displayed in Callendar House. The exact moment of the discovery is unknown, but we know that the tile became part of the local heritage collections in 1926, when the Mungo Buchanan collection was acquired by the Falkirk Museum. The tile, made of clay, has an almost square shape and measures 9.4 x 8.4cm, with a thickness of 4.8cm. In modern times, to fix a fracture, the tile had been patched with plaster. On the upper side of the tile, we can see a dog’s paw print. Looking at the size of the paw, it is likely that the dog was a medium/large-sized dog. The breed, of course, is impossible to tell.

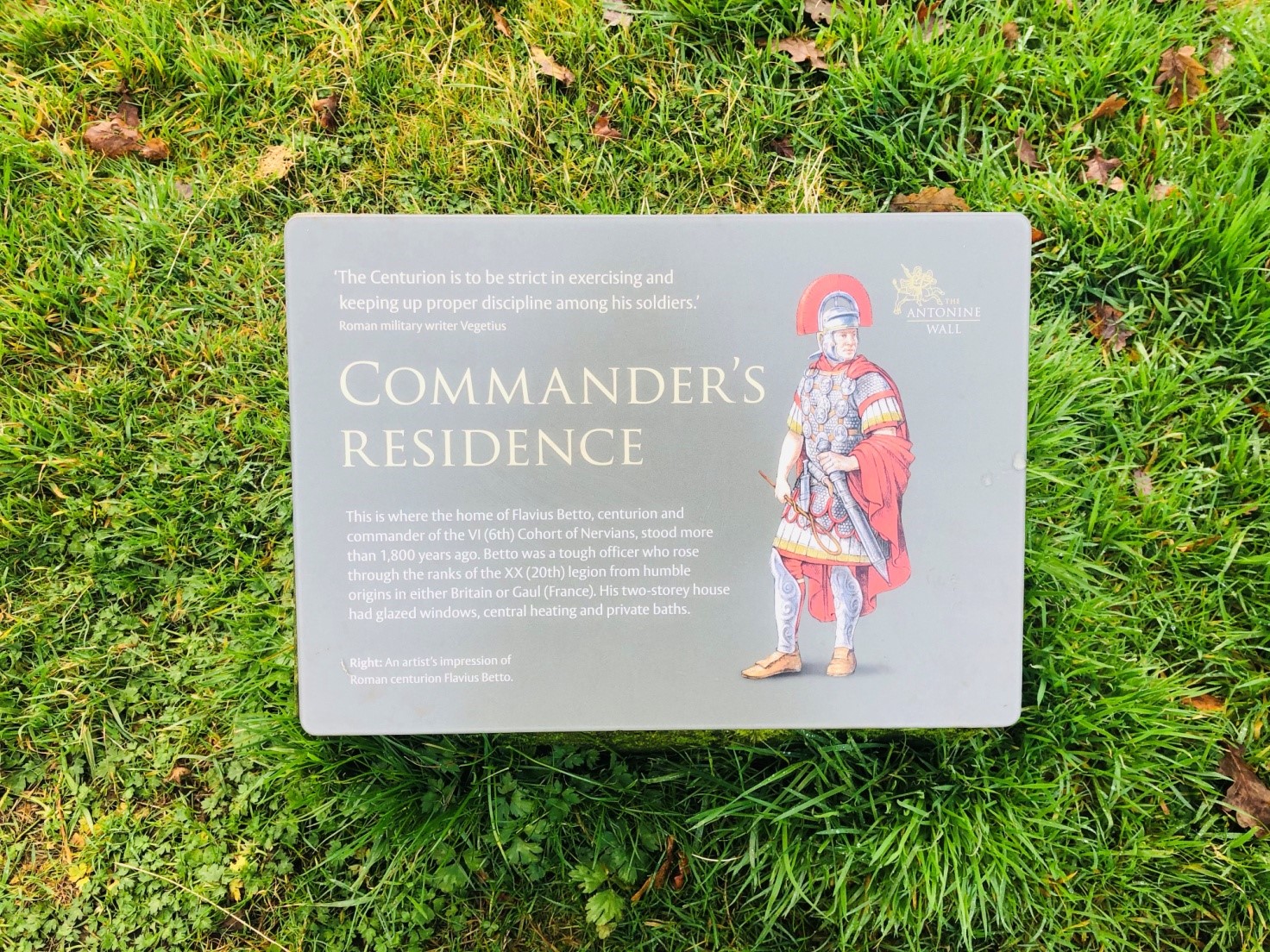

The Roman fort where the tile was found, Rough Castle, is the second smallest fort on the Antonine Wall but also the best-preserved. The site is accessible after a short walk from the Falkirk Wheel, through the woods. Once you arrive, it is hard to place the fort in the area and imagine what it looked like 2,000 years ago. Many heritage interpretation panels are available to assist us, depicting a map of the fort, descriptions of the buildings, and where these were erected.

Canine Questions

The fort was excavated in the early years of the 20th century and a report of the dig, mainly written by Mungo Buchanan, can be found in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (vol. 39). The description of the findings is very interesting and exhaustive, but unfortunately there is no mention of the tile with the paw print. That was when the wide knowledge of Geoff Bailey came to my aid. The questions to which I wanted answers were:

- What type of tile are we looking at?

- Was the paw printed intentionally or not?

Geoff explained to me that this was not a roof tile. Rather, its thickness suggests that it was part of the hypocaust, which was the heating system used in Roman buildings. More specifically, the tile comes from one of the underfloor columns (pilae). A heated house was not accessible to all people, only the wealthy. Considering our case and the type of settlement, a military fort, we can assume that the tile belonged to the officer’s house.

While, in my mind, I imagined a Roman soldier playing with a dog and impressing her paw on the raw tile, Geoff brought me back to reality: the paw was likely to have been impressed by a dog walking on the tiles while these were drying before being cooked in the furnace.

Roman Dogs

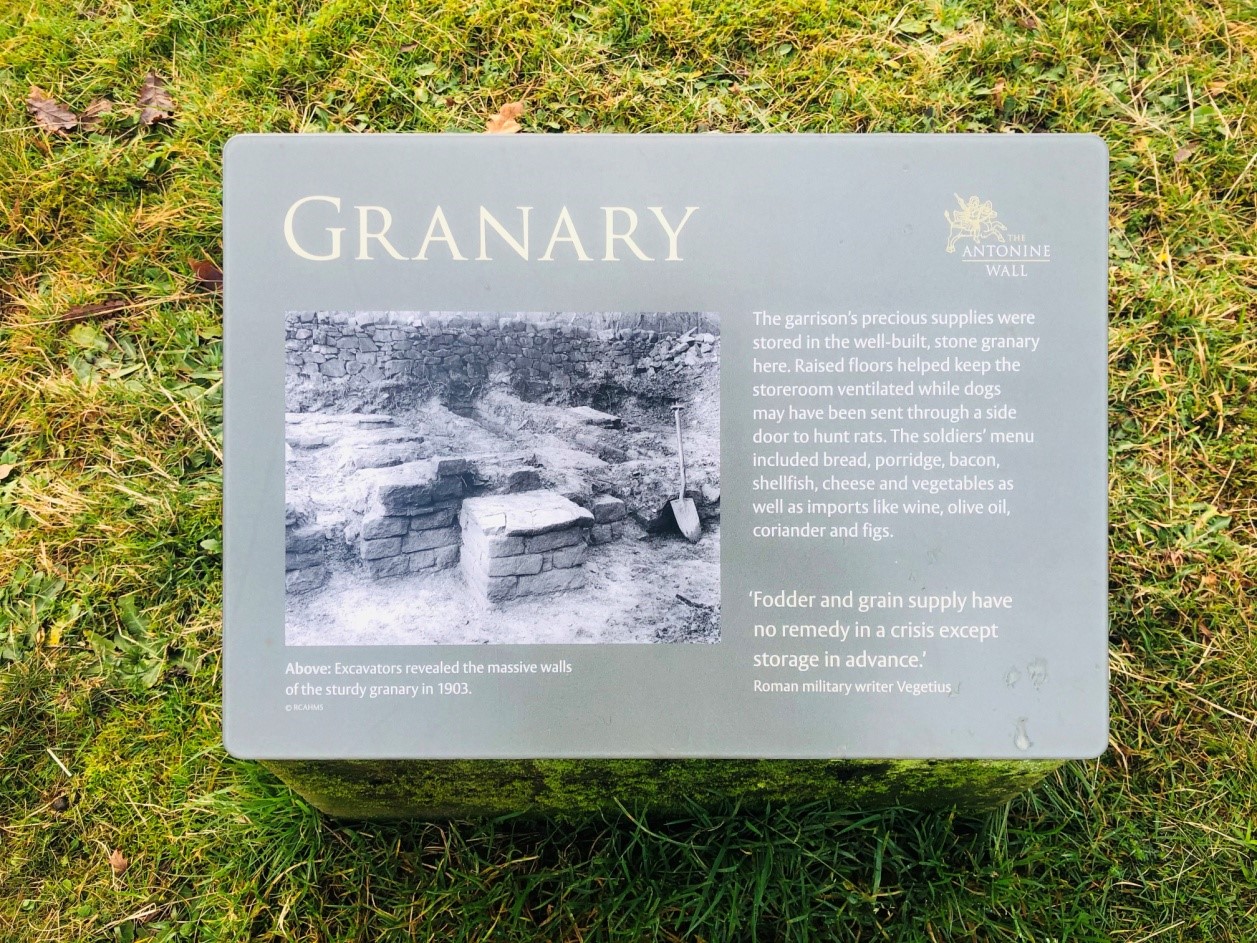

What do we know about dogs in the Roman world? And what about the presence of dogs in Roman forts? Many dog bones found in the fort of Vindolanda along the Hadrian Wall show that dogs of very different sizes and breeds lived with the soldiers. Some of them were as small as Chihuahuas, while others were large Molossers. Big dogs were mainly used for hunting, but they must have been employed also as guard dogs. The Greek geographer Strabo (1st century BC – 1st century AD) wrote that dogs were exported from Britannia for their skills in game hunting, and were also used as war dogs by the Celts. The small breeds, instead, were kept for keeping house mice out of the buildings and for gaming. Dogs used as rat hunters were probably present in Rough Castle, as this seems to be suggested by a door in the granary that led to the sub-floor of the building.

Companions

We cannot, of course, forget that dogs were also kept by the Romans as companions. The loss of a pet was heart-felt by some people in the past as much as it is today. The epitaph of one dog, Margarita (the Greek name for “pearl”), shows us the strong feeling that existed between the dog and her owners in ancient times. The monument was set up in the 1st-2nd century AD and it is now displayed at the British Museum (CIL 06, 29896). The text says:

“Gaul gave me my birth and the pearl-oyster from the seas full of treasure my name, an honour fitting to my beauty. I was trained to run boldly through strange forests and to hunt out furry wild beasts in the hills never accustomed to be held by heavy chains nor endure cruel beatings on my snow-white body. I used to lie on the soft lap of my master and mistress and knew to go to bed when tired on my spread mattress and I did not speak more than allowed as a dog, given a silent mouth. No-one was scared by my barking but now I have been overcome by death from an ill-fated birth and earth has covered me beneath this small piece of marble. Margarita” *

Our dog from Rough Castle was not lucky enough to be remembered by such moving words. Still, it left a (paw) print that crossed 2,000 years and has reached us. Many questions on its identity and that of its owners remain open, but there is something we can say for sure: what was a small step for a dog can be seen as a giant leap in our knowledge of the history of Falkirk.

By Tatjana Sandon, Hidden Heritage Online: Ancient Falkirk volunteer.

With thanks to Geoff Bailey and Sabine Hellmann for their assistance.

*Translation, information and photos can be found at the British Museum.