Ever wondered why there’s a lion attacking an eagle on the Grangemouth war memorial? Ever wanted to know where the memorial was originally going to be constructed? Read on to find out…

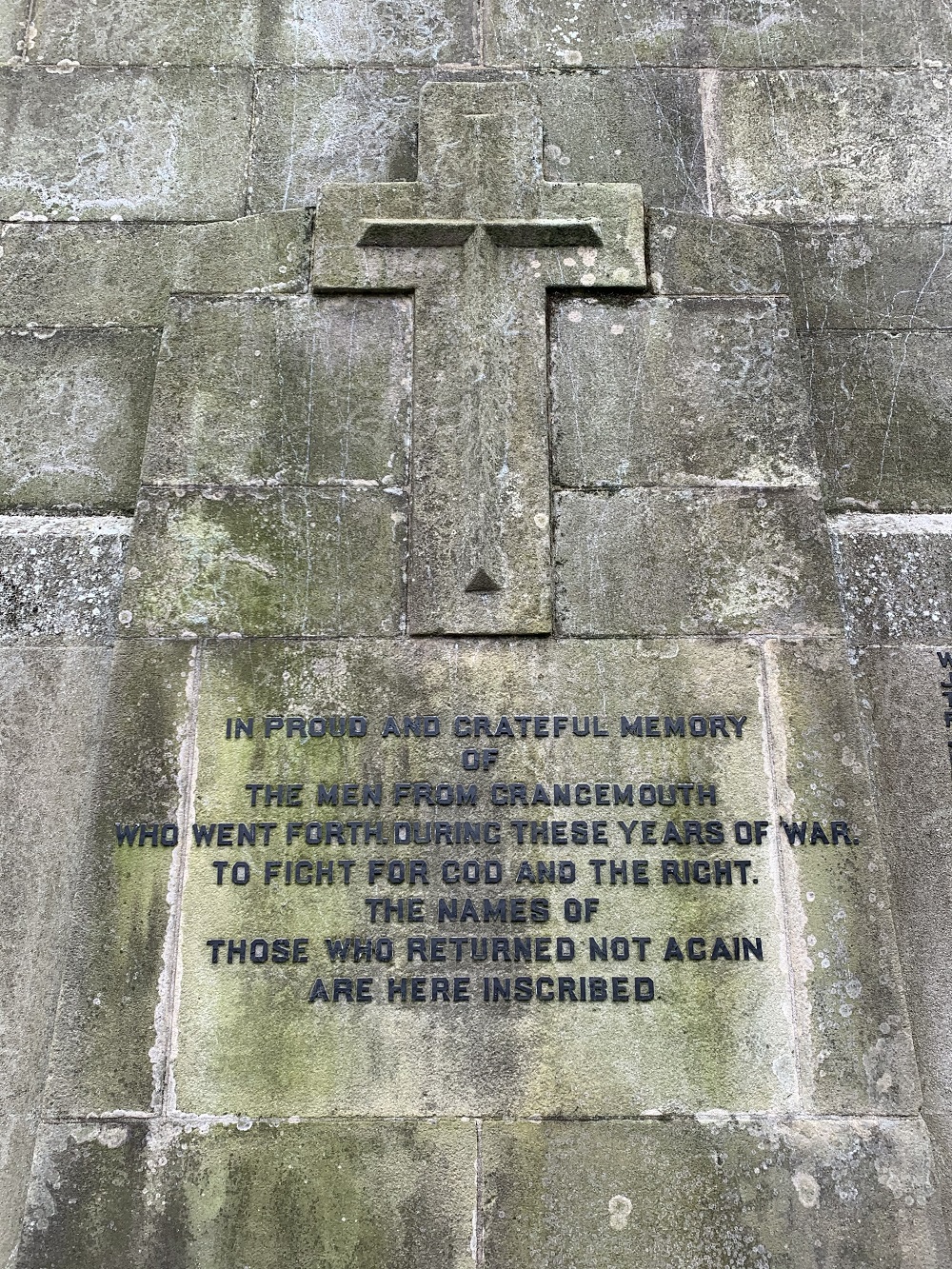

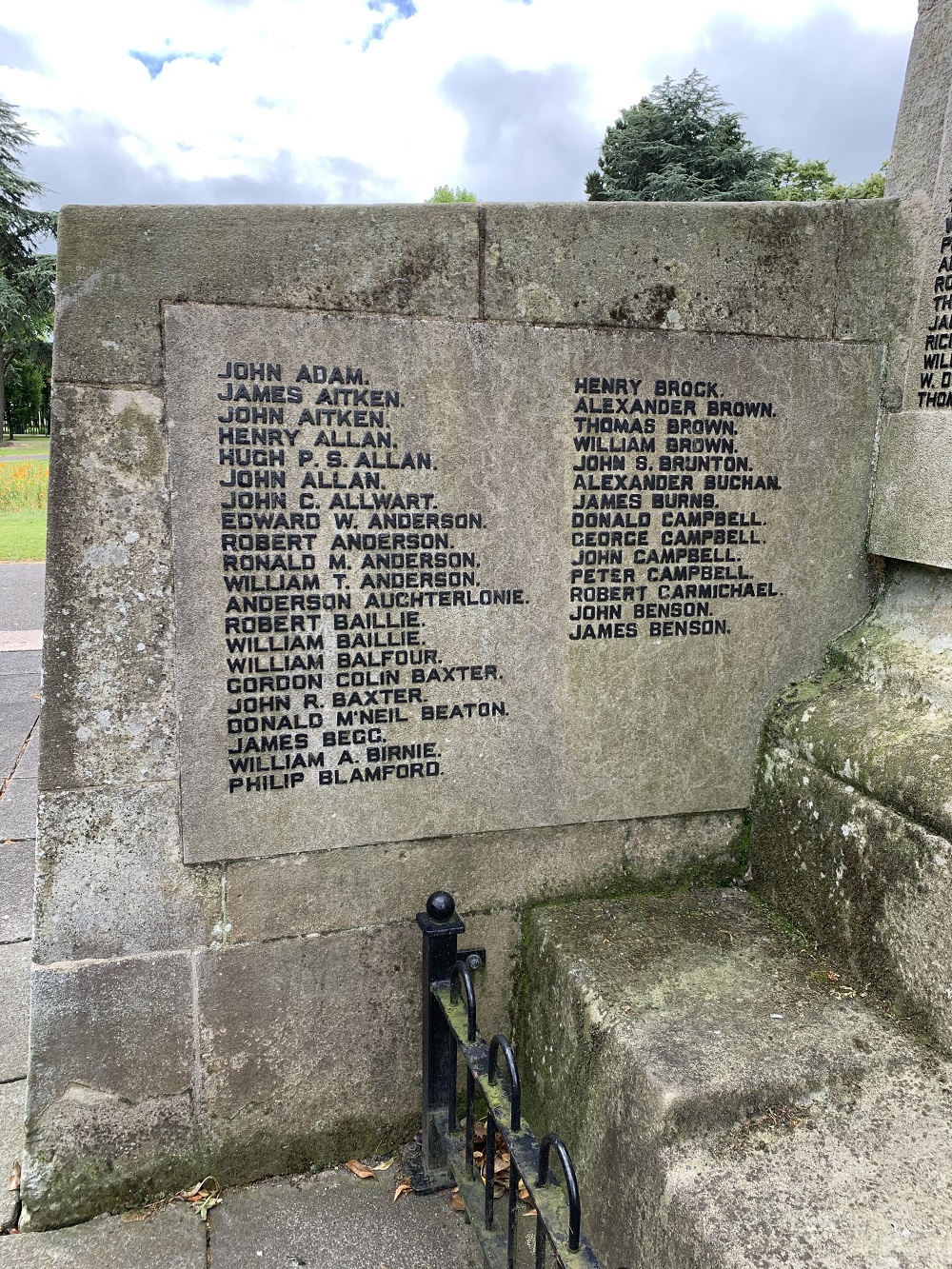

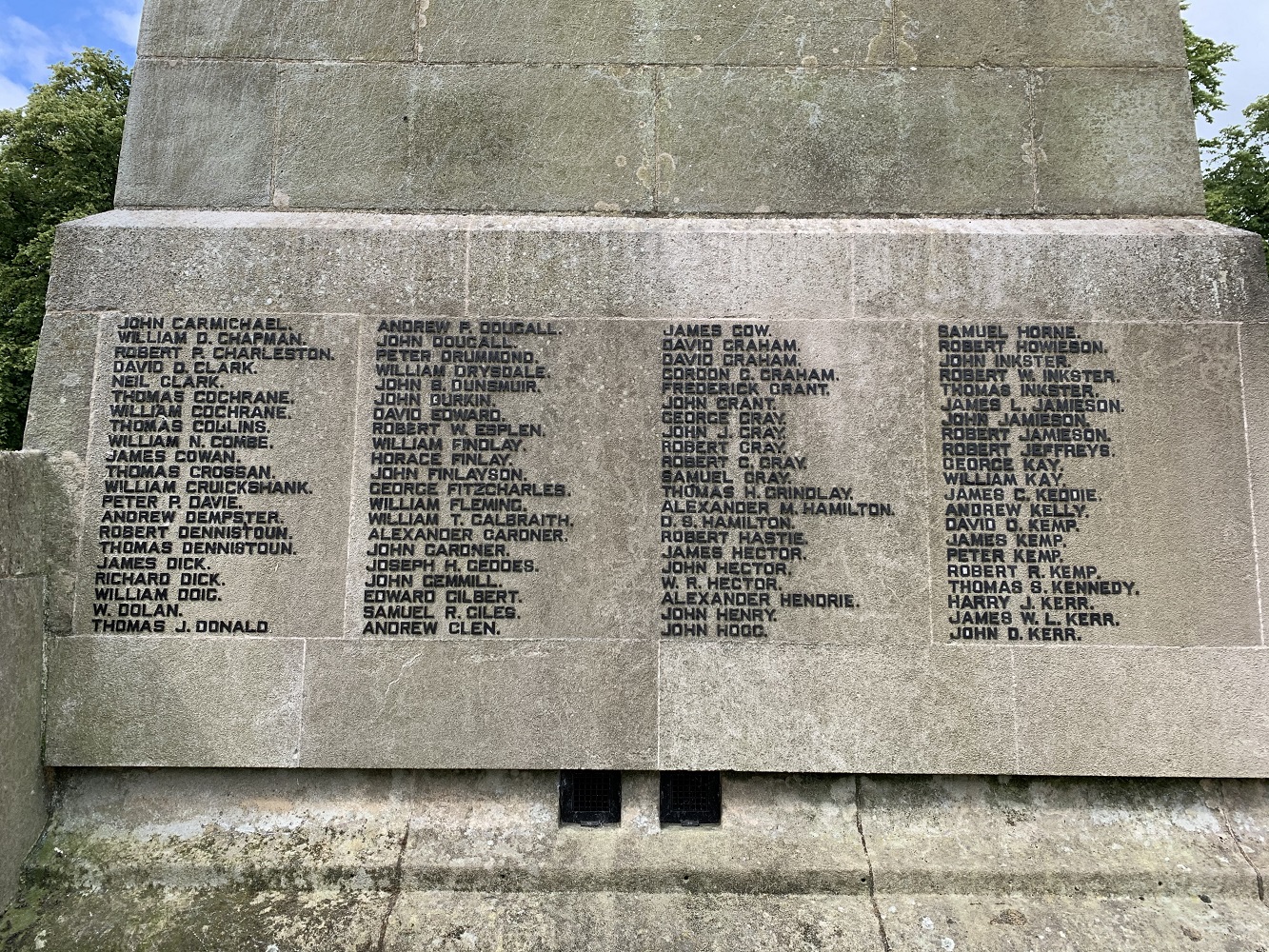

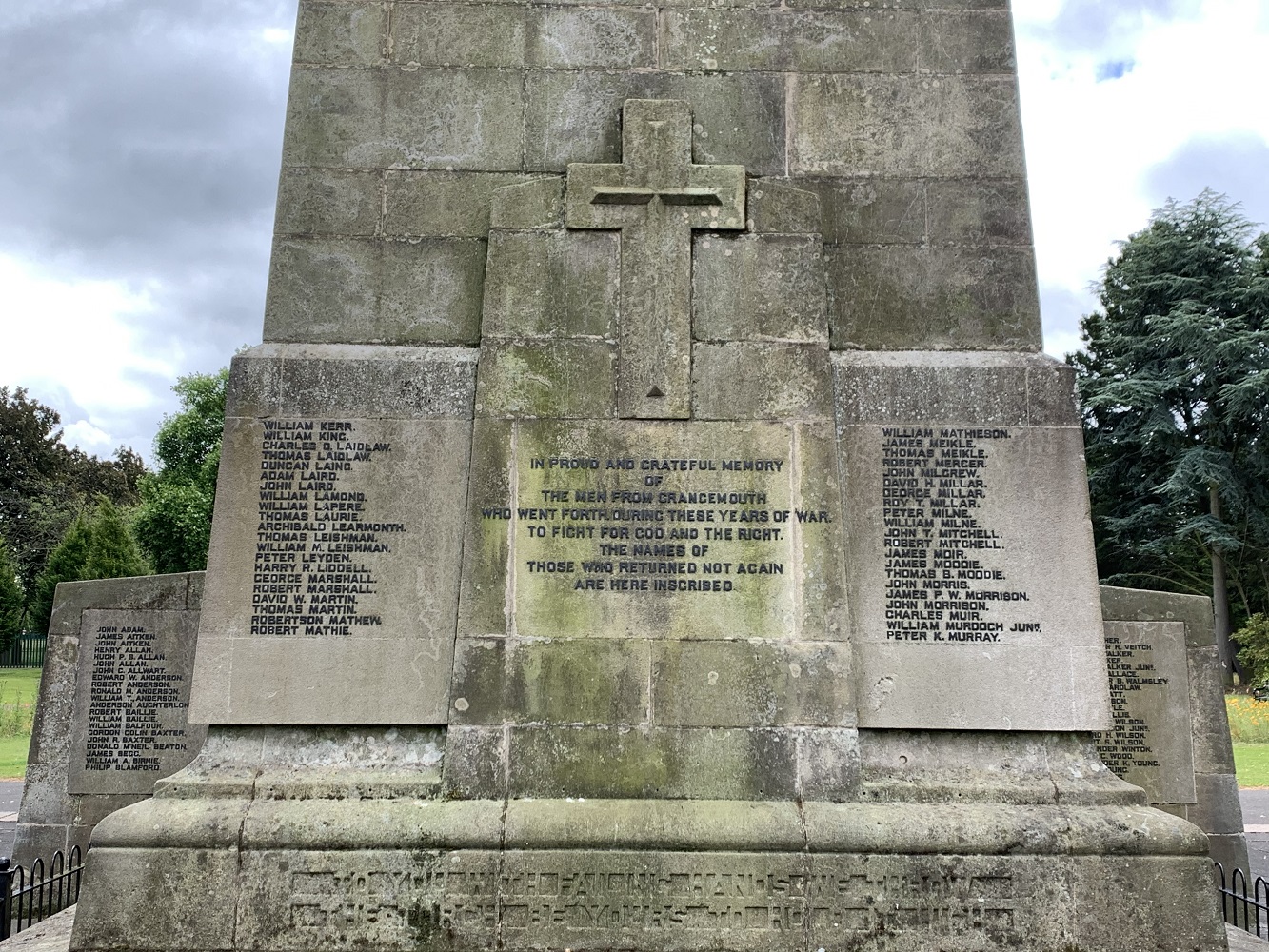

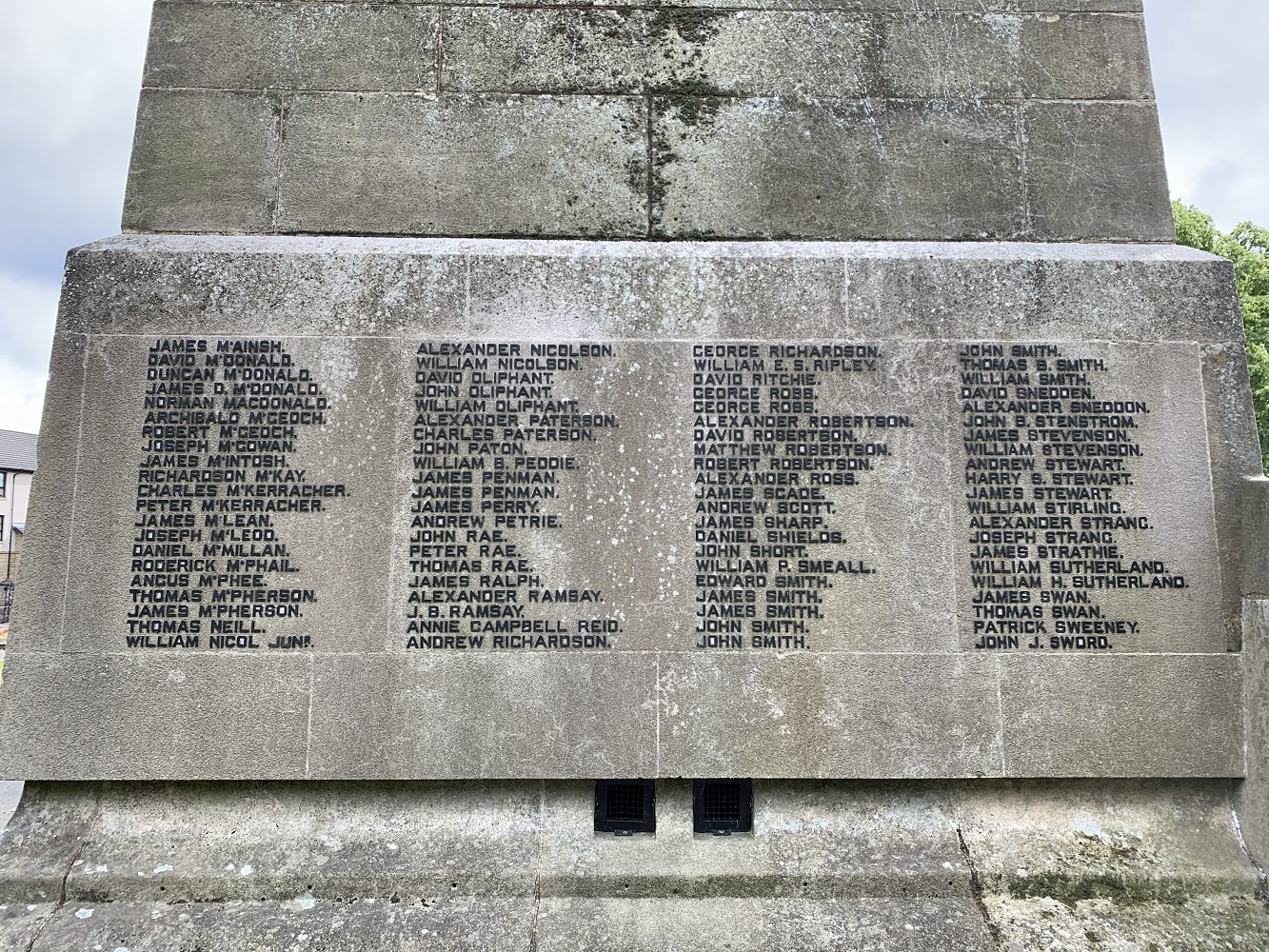

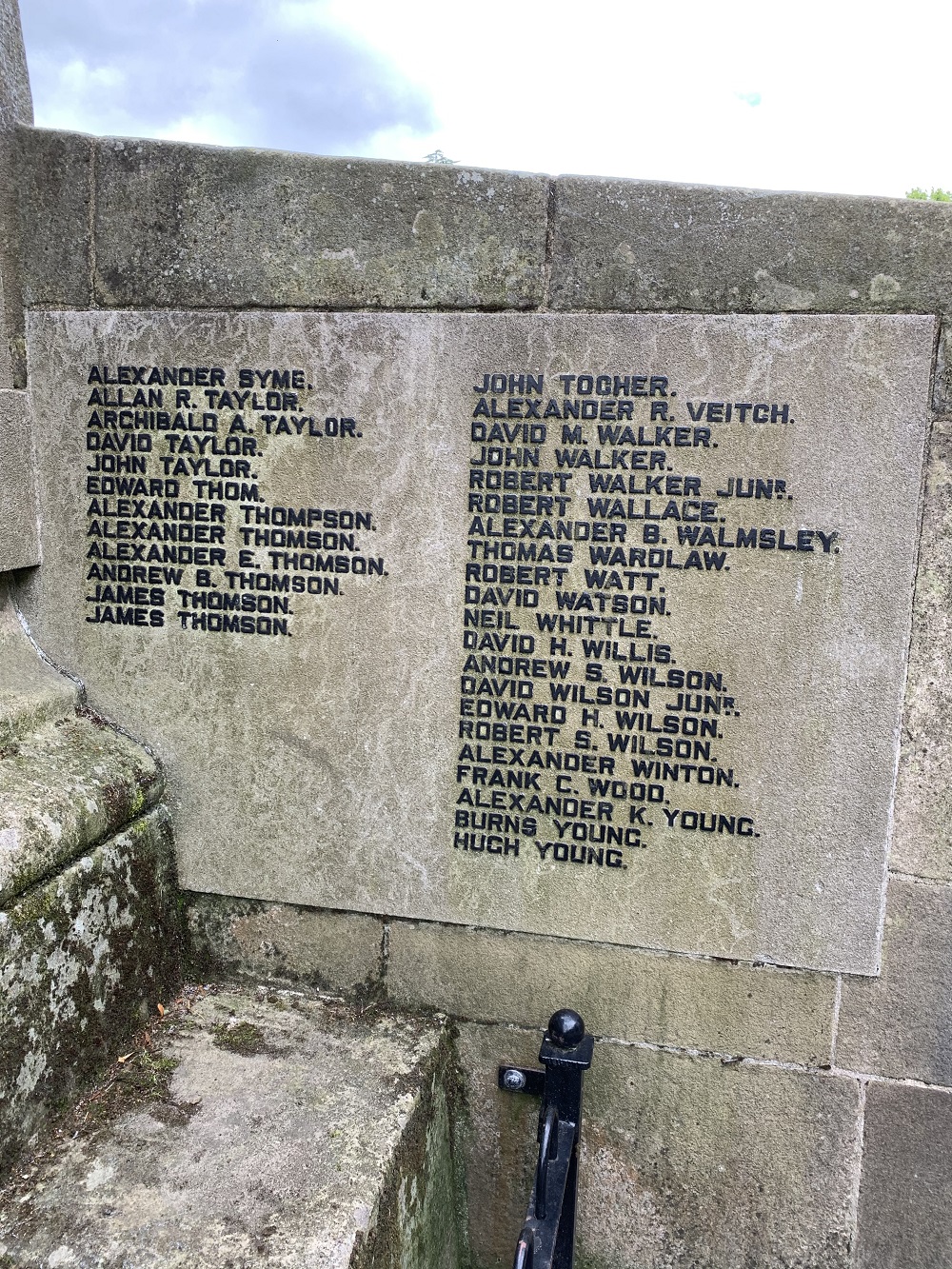

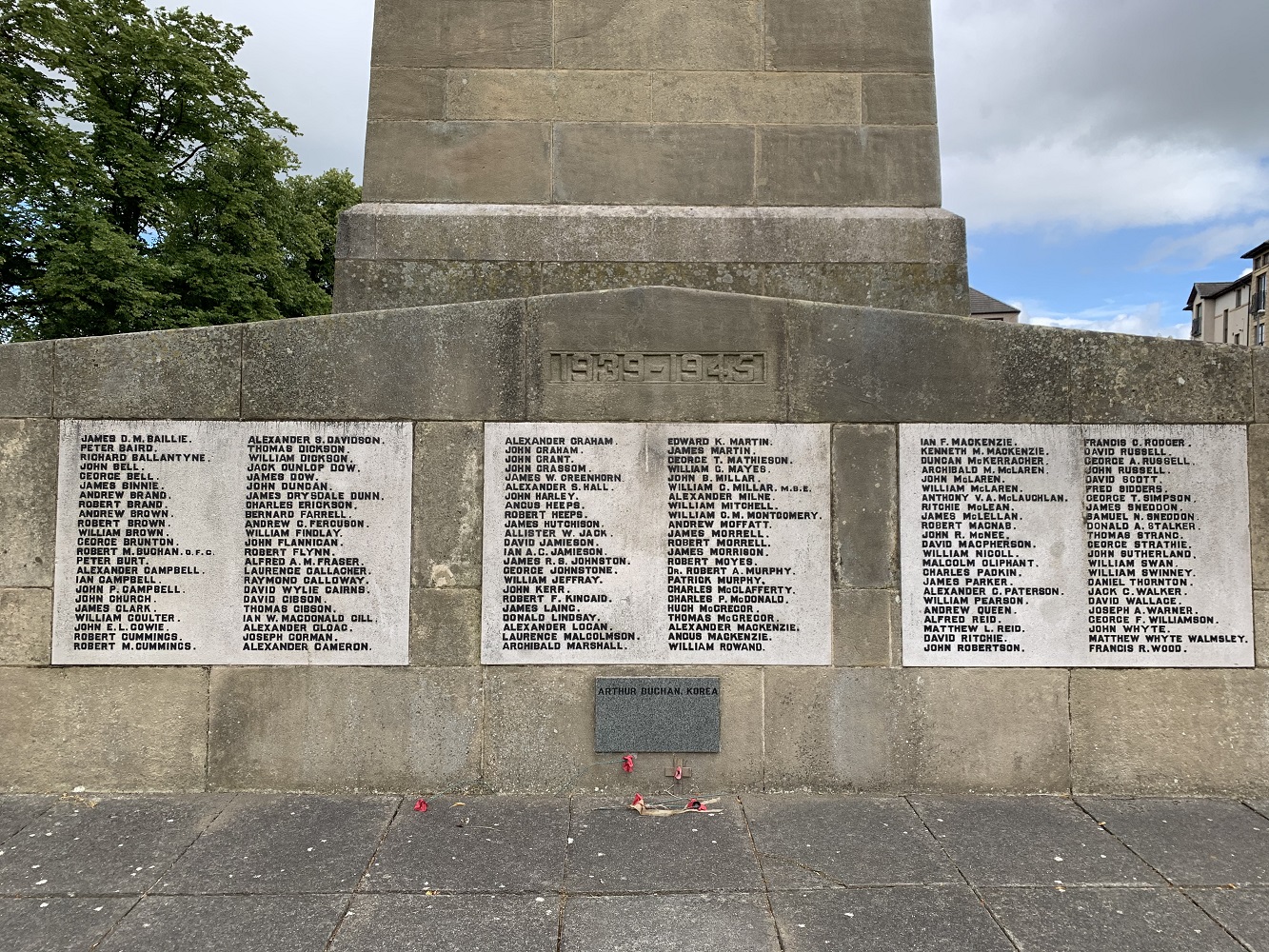

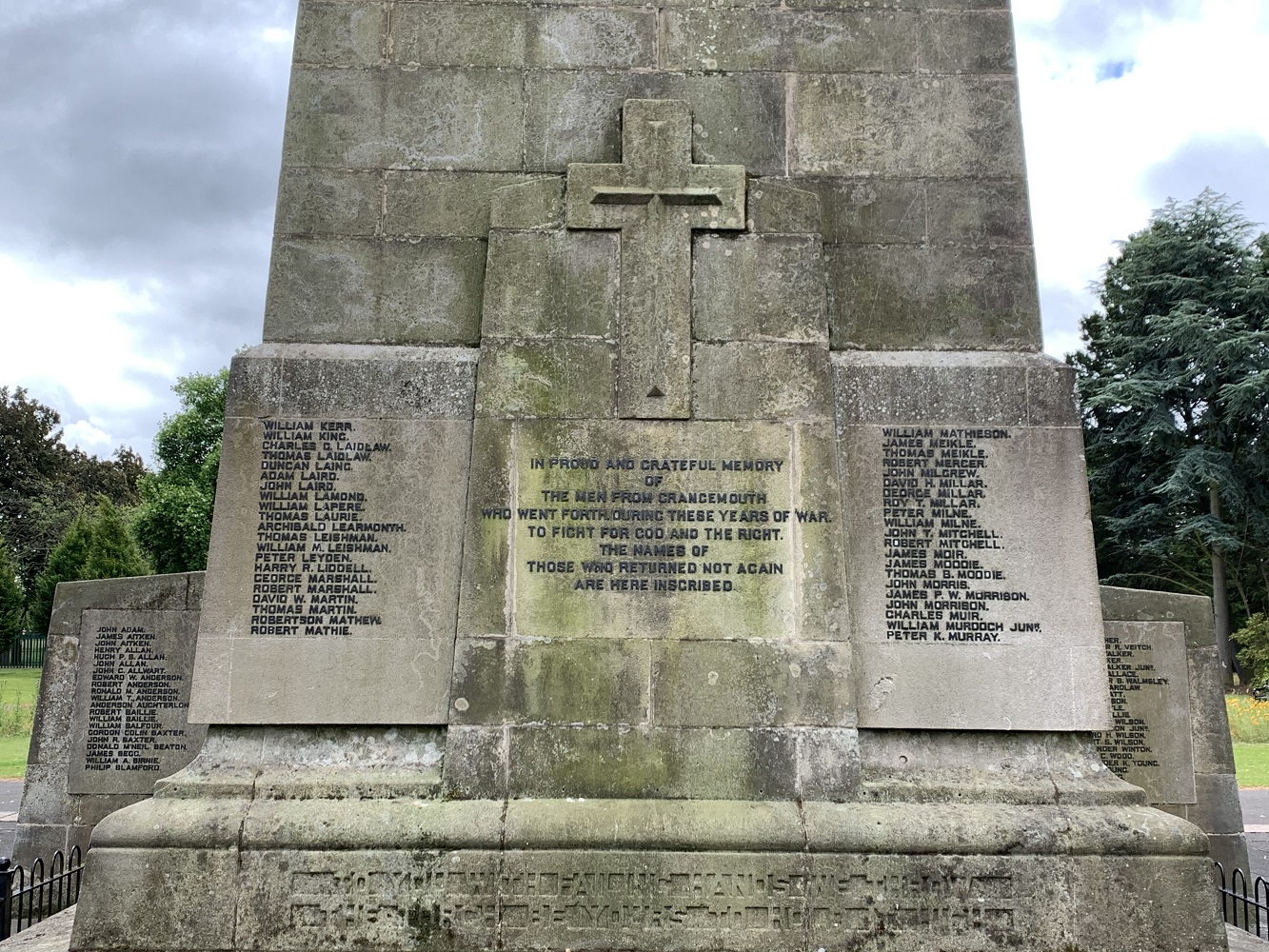

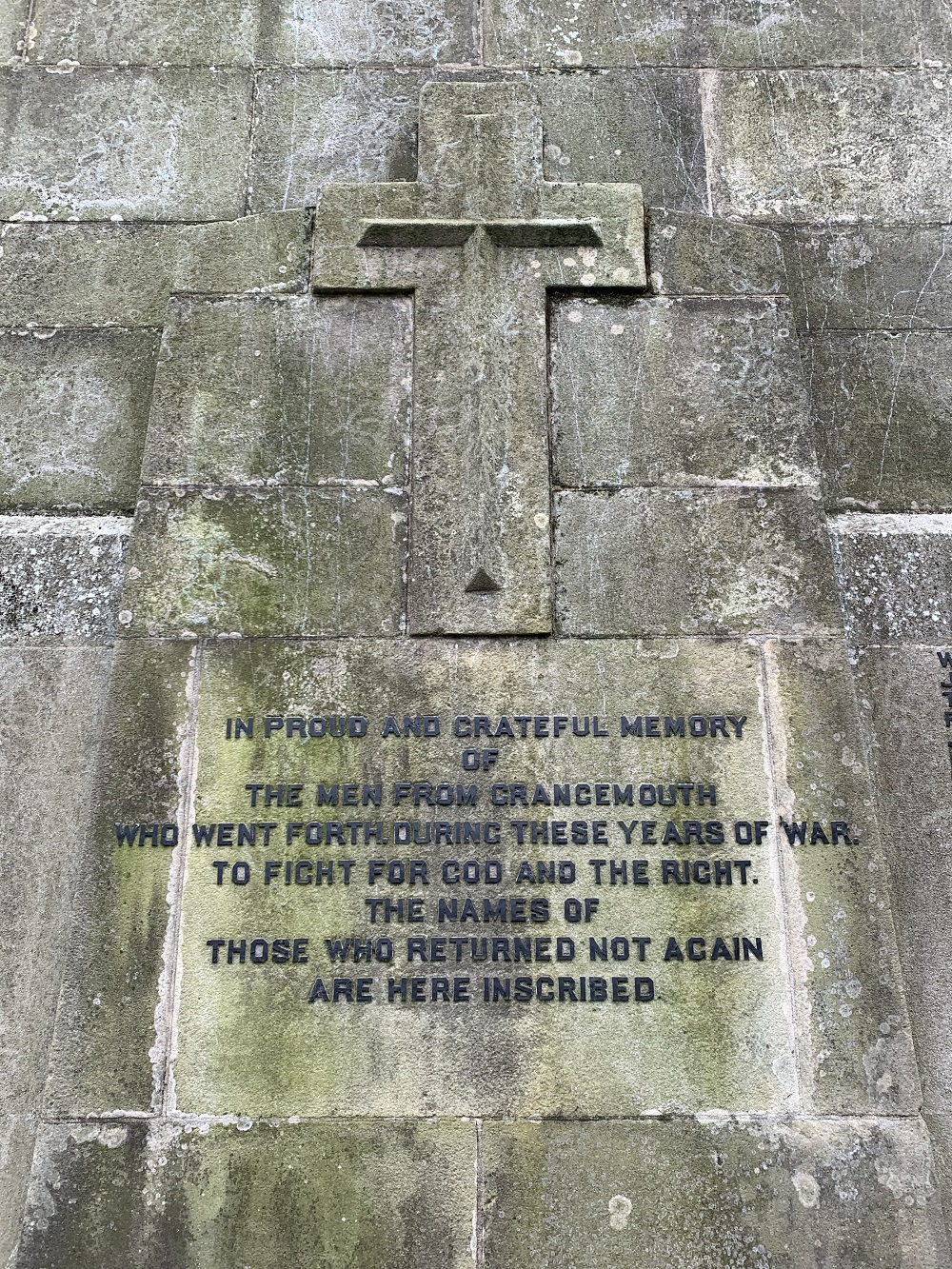

Grangemouth War Memorial was unveiled on Saturday 22nd September 1923 by General Sir Ian Hamilton after years of discussion, public meetings, and fundraising. It was designed by Sir John Burnett and sculpted by Alexander Proudfoot (both from Glasgow). The cenotaph is 27 feet tall, crowned with a sculpture depicting the British lion attacking the German eagle – there was some controversy around this iconography, but we’ll come back to that later. The names of men from the First World War, Second World War and Korean War are engraved on plaques on the lower part of the cenotaph, as well as on two “wings” on either side. The memorial is flanked by two stone gates, and railings, which lead into Zetland Park. The front contains the following inscription, underneath a carved stone sword:

In proud and grateful memory of the men from Grangemouth

who went forth during these years of war to fight for God and the right.

The names of those who returned not again are here inscribed.

Competing Sites

A War Memorial Committee was founded to help with the planning and funding of the memorial, and held their first meeting in February 1919. They held a mix of committee meetings and public meetings, in order to get opinion on the various requirements for actually constructing a war memorial. One of the biggest decisions to make was where the memorial should be constructed. The original sites proposed were: at Charing Cross; in front of the Town Hall; where the Glasgow and Edinburgh Road were to lead off into the new housing area at Newhouse; and the public park (Falkirk Herald 11 December 1920, p.5). The consensus leaned towards erecting it at Charing Cross – because it was the most inexpensive site, and because soldiers had gathered in that area before leaving to go to the war. The arguments about location raged on for two years, with the Falkirk Herald even announcing in February 1921 that Charing Cross was the chosen site (12 February 1921, p.3). It would take until the end of 1921 for the current site in the park to be conclusively chosen (Falkirk Herald 3 December 12 1921, p.9).

Funding the Memorial

There was a War Memorial Fund to help with the building of the memorial. Collections and subscriptions from the local population helped build this up, as well as the interest that accrued on the money. Events also helped raise money for the memorial. For example, the Grangemouth dockyard employees’ annual sports day in June 1920 raised around £120 (Falkirk Herald 26 June 1920, p.4). The amounts received in total were: £1929 0s 8d in subscriptions; interest on loans added a further £357 8s 8d; and five gentlemen added £1882 4s 6d to cover the costs of the ornamental gates, etc. Therefore, the total sum raised for the memorial was £4168 13s 10d (Falkirk Herald 20 December 1924, p.8). A final meeting of the War Memorial Committee in December 1924 highlighted all of the costs associated with the construction of the memorial:

- the cost of the memorial, including builder, sculptor, and inscription work, and the architect’s fees was £2478 18s 3d;

- the ornamental gates, pillar and railings came to £1625;

- printing, stationery and advertising costs were £64 5s 1d

(Falkirk Herald 20 December 1924, p.8).

Unveiling the Memorial

The memorial was unveiled, as noted above, on the 22nd September 1923. The Committee, local people, local Guides and Brownies, and, of course, Sir Ian Hamilton, were amongst those present at the unveiling. This became news all around the United Kingdom, thanks to Hamilton’s speech, which was reported all over the country, from Glamorgan to Orkney:

“General Sir Ian Hamilton, speaking, on Saturday, at the unveiling of the Grangemouth War Memorial, said there was now everywhere in our country an unprecedented reaction against the processes of war, even where it was least expected to find it – among the whole of the ex-Service men. That being so, it was “up to us” now or never to take stock of our experiences and seek to formulate some mighty resolve. There was one way of immortalising the memories of those who died for us by making the League of Nations truly representative of Europe. If that were done we might succeed in “anticipating the resurrection by creating a Judgment Seat on earth where small as well as great would get justice at the cost of lawyer’s fees instead of soldiers’ blood.””

(The (Hull) Daily Mail 24 September 1923, p.1)

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

Controversial Designs

And now we come to the controversy surrounding the design of the memorial, and the British lion attacking the German eagle. The first time this is really mentioned is in an article in the Falkirk Herald, just some weeks before the unveiling of the memorial. Mrs Wilkie, one of the Committee members, objected to the “suggestion conveyed by the addition of an eagle in this attitude, as she held that the British should exhibit a spirit superior to this” (Falkirk Herald 5 September 1923, p.3). Several other members agreed with her on this point. There isn’t any mention in the paper of this again, until August 1931, when the following was reported:

“Grangemouth War Memorial was the subject of a discussion this week. A visitor to the port saw the memorial for the first time, and, to put it mildly, he was shocked. He could hardly believe that such a thing as the lion tearing the German eagle was allowed to stand. In his opinion, it was not indicative of the present-day spirit. This was peace-time, and what would be the feelings of German sailors who came to Grangemouth on seeing the memorial? He thought the whole thing should be removed. It was explained to the visitor that there had been some misunderstanding when the memorial was first erected, but his answer was that Grangemouth had had plenty of time in which to rectify it. It showed very bad taste!” (Falkirk Herald 15 August 1931, p.6).

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

Discussions in 1948 returned to the lion and the eagle, and a new Committee was formed in order to organise the commemoration of those who died in the Second World War. However, the main priority for this new Committee was the engraving of these new names, and with little money being raised, this was the essential use for it – not fixing the imagery atop the cenotaph.

By Louise Bell, Great Place volunteer 2020.