Find out more about the famous Grangnemouth docks through the history of the Grangemouth Dockyard Company Limited.

The Formation of Grangemouth

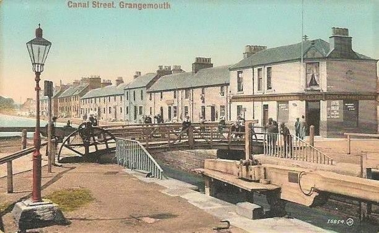

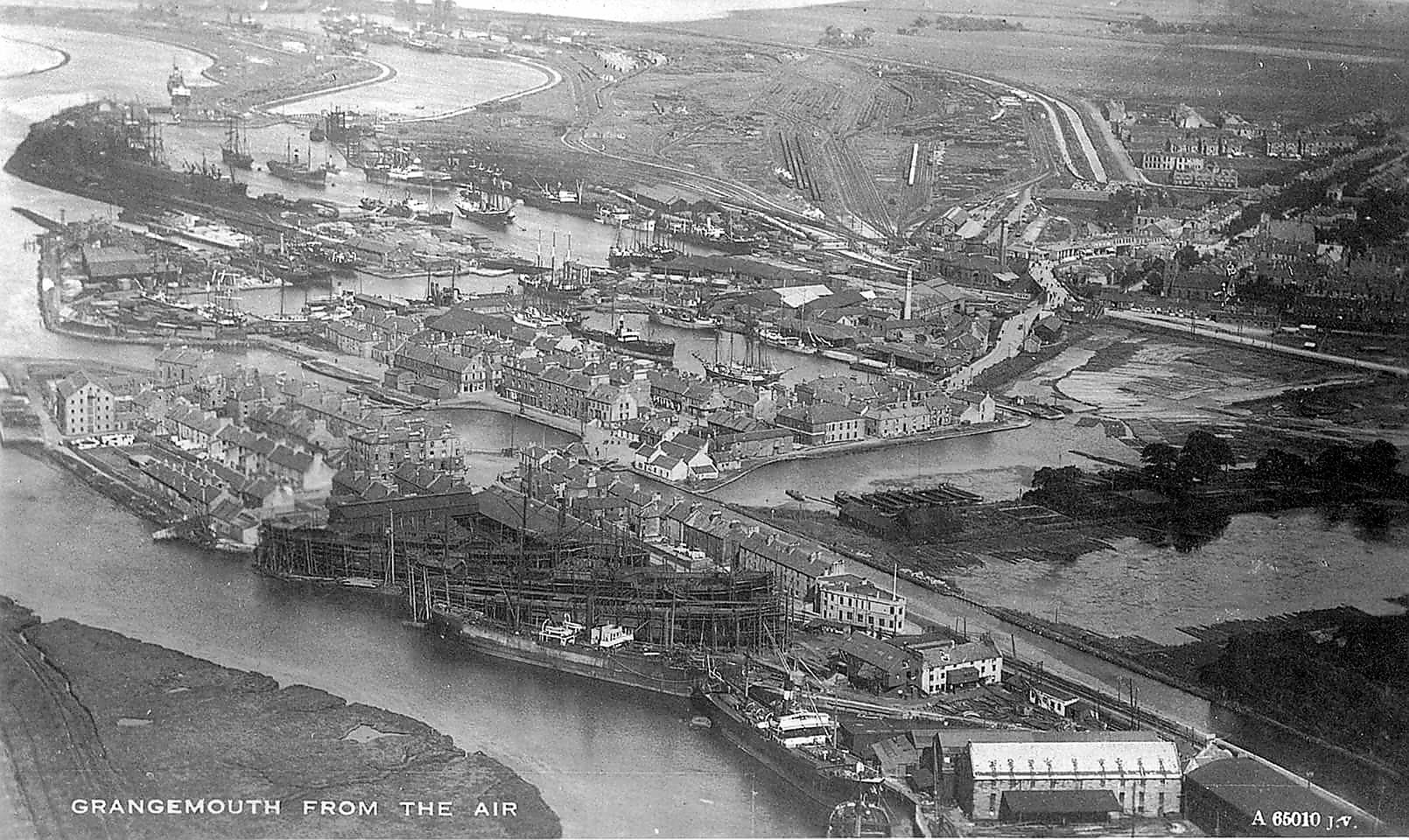

Sir Lawrence Dundas was a major supporter of the idea to build a waterway connecting the east and west coasts of Scotland. So it was that when construction on the Forth and Clyde Canal began in 1768, it did so at its eastern end on Dundas family lands. The canal was completed in 1790, and went on to play a vital role in Scotland’s industrial development.

In 1772 Sir Lawrence laid the foundation stone for the first house to be built between the River Carron and the canal, beginning the formation of Grangemouth. These houses were to provide accommodation for workers on the canal.

Sir Thomas Dundas continued the work his father had started, supporting social services and new industries, as well as expanding the infrastructure of the town by building roads and having the Grange Burn diverted in 1797. Grangemouth began to flourish. New industries developed, including pottery, brick-making, fish-curing, whale-boiling, and coal production, as well as trade in timber and grain. Of note were those trades associated with shipbuilding, such as rope-works and, from 1805, sail-making. A new school was built around 1808 (named the Zetland in 1827); a Post Office in 1809; and a Custom House in 1810 (“History of Grangemouth”).

Shipbuilding: The Early Years

There have been many shipbuilders in Grangemouth over the years: J. Welsh (1782); J. Cowie (1788); Alexander Hart (1790); John Allan (1804); Thomas Adamson (1827); James Adamson (1831); Adamson and Co. (1863); Dobson and Charles (1879); William Drake (1886): and The Grangemouth Dockyard Company (1885).

The first ship built in Grangemouth was a 47-ton sloop, which is a single-mast sailboat, usually with one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft. It was built by J. Welsh in 1782 and named Jean and Janet. J. Cowie took over the boatyard in 1788 and his first ship was also a sloop, this time a 56-ton vessel called Jean (“History of Grangemouth”).

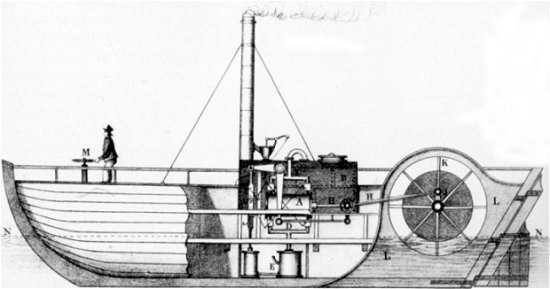

Perhaps the most famous boat to be built was the Charlotte Dundas. The first version was built by Alexander Hart in 1801 but the engine was found to be underpowered. In 1802 the Mark II version was built in Hart’s yard by John Allan.

In 1811 Lord Thomas Dundas ordered the building of a Graving Dock. “Graving” is an obsolete nautical term for scraping, cleaning, painting, or tarring the underwater part of a ship. Nowadays the common term is a dry dock. This was to enable the local shipyards to build larger ships including ocean-going vessels. This was the first of three dry docks, the other two were constructed about a century later.

Grangemouth Dockyard Company

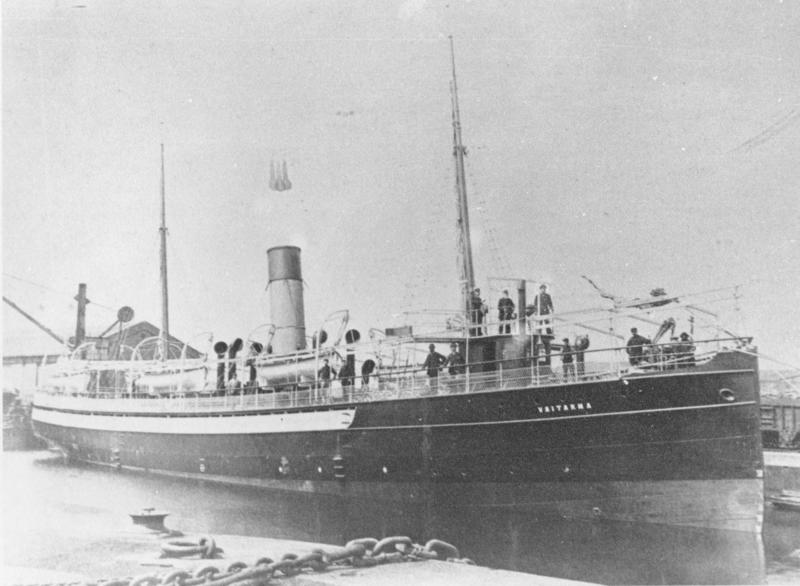

In 1885 Grangemouth Dockyard Company built its first steamship, the SS Vaitarna. Two years later the boatyard was visited by Andrew Carnegie and his wife Louise, who the same day had gifted £600 towards the building of a new library. They witnessed the christening and launch of the Mexican steamer Tabasqueno.

The Grangemouth Dockyard Company also had other yards in Scotland, one in Alloa (1889-92), and another in Ardrossan (1891-2). Between 1900 and 1907 it was named the Grangemouth and Greenock Dockyard Company Limited, before becoming the Greenock and Grangemouth Dockyard Company for the next decade. In 1918 the company divested its yard in Greenock and was renamed, finally, the Grangemouth Dockyard Co. Ltd.

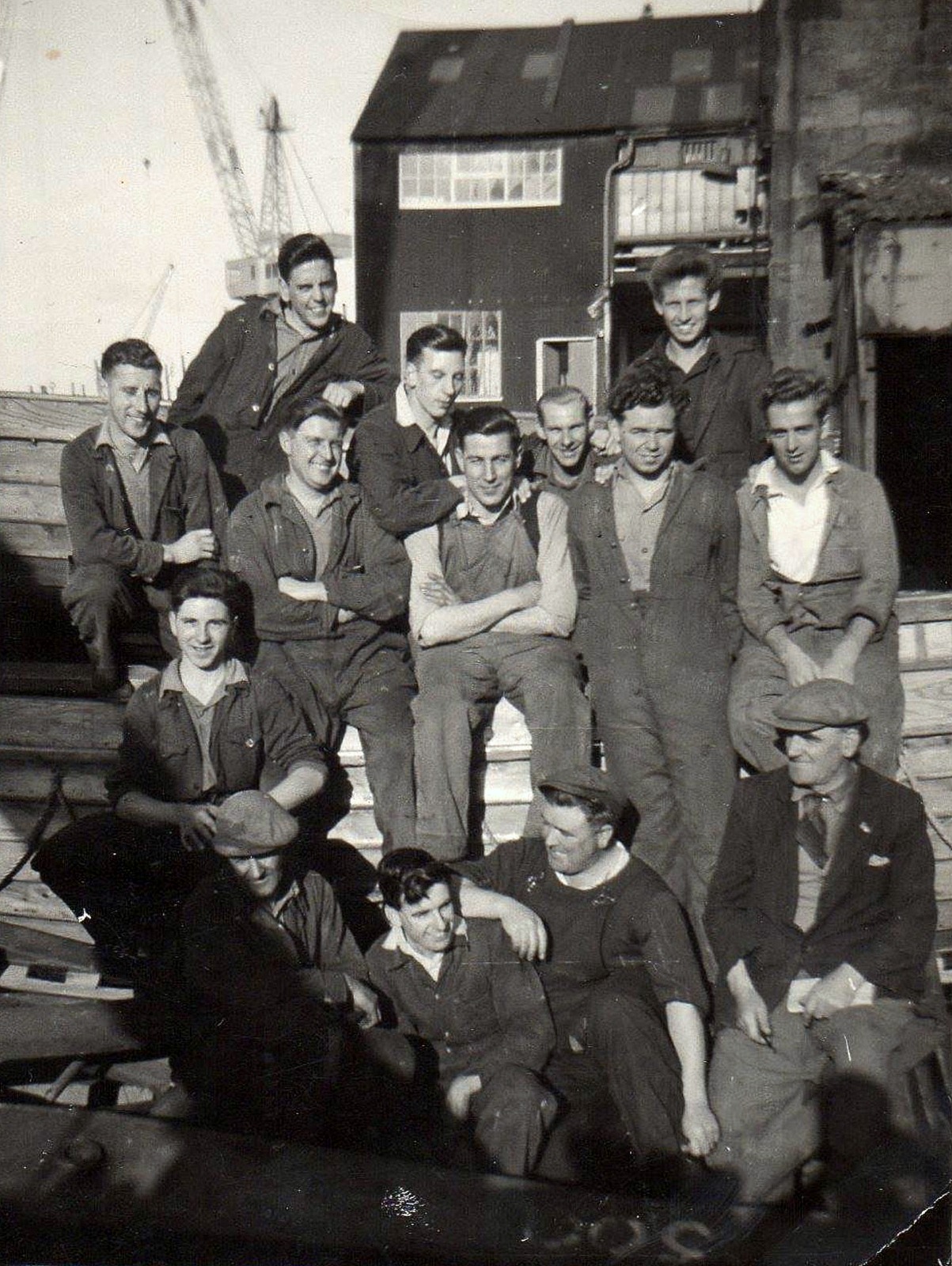

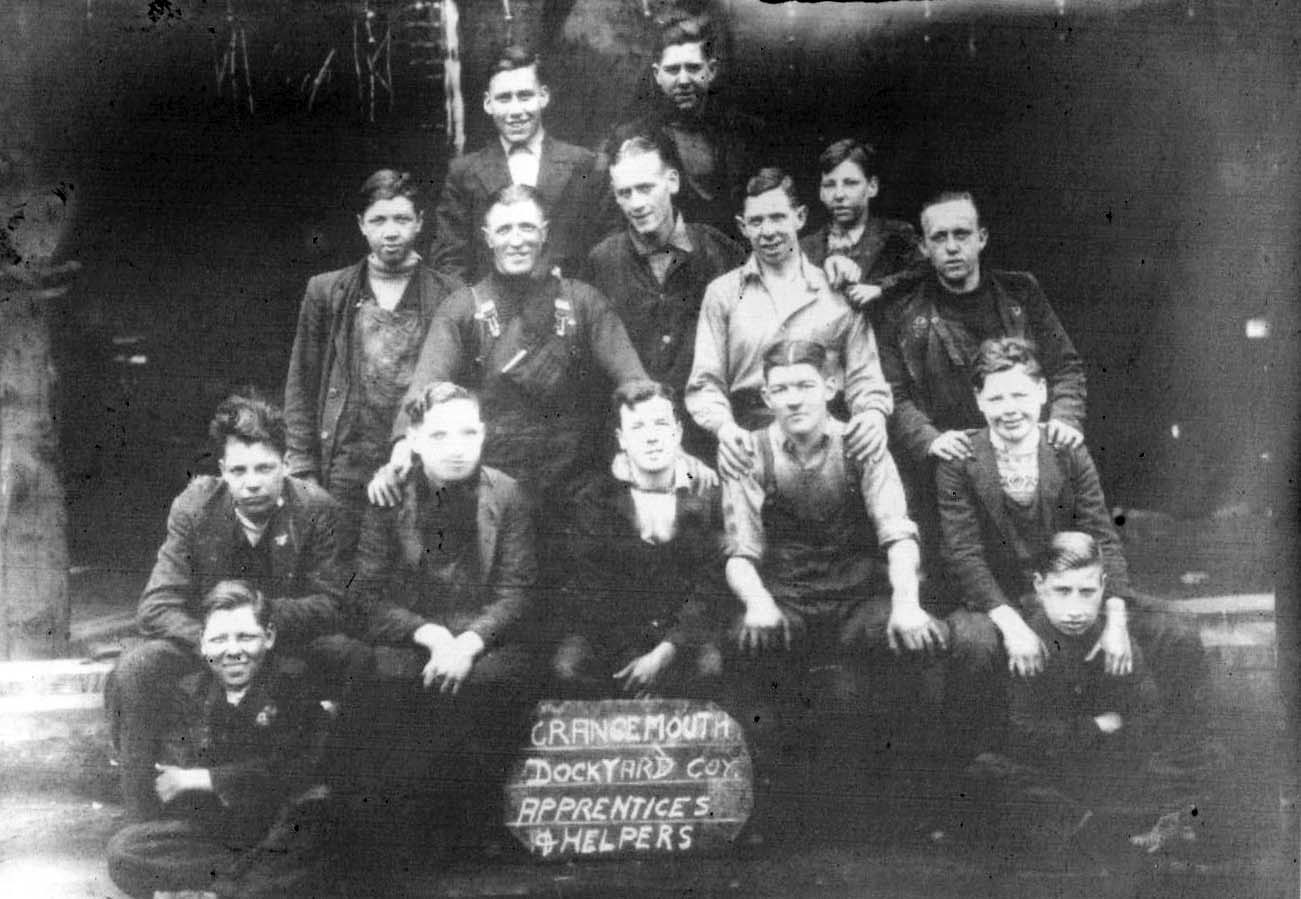

Many trades are involved in shipbuilding, becoming more numerous as ships became more sophisticated. In the early days, of course, wooden ships were constructed, which required the skills of carpenters, sail-makers, riggers and caulkers. When iron and steel were introduced new trades were needed: platers, riveters, hole-borers, welders, burners and painters, to name a few. As time and technology moved on, there was a need for plumbers, engineers, electricians and turners.

The War Years

During World War I, the boatyard was extremely busy, working around the clock, mainly for the Admiralty. At this time the boatyard was extended, with extra dry-docking made available by using the Dock Gates at the Old and Carron Docks, known as Middle and Carron Dry Docks.

During World War II the boatyard was again extended and the nature of work diversified. Notably, submarines were now repaired and refitted for both the British and Dutch fleets. The boatyard also produced ships, mainly for the Admiralty and the Ministry of War and Transport. Seventeen ships present at the Normandy Landings were built entirely in Grangemouth and another 44 merchant ships had been repaired and prepared for the landings (Bailey p. 346). In addition, over 100 other ships present at the landings had had work done on them at one time or another by the boatyard. It has been calculated that 18% percent of the British fleet had seen work done at some time by Grangemouth Dockyard Co. Ltd (Bailey p. 346).

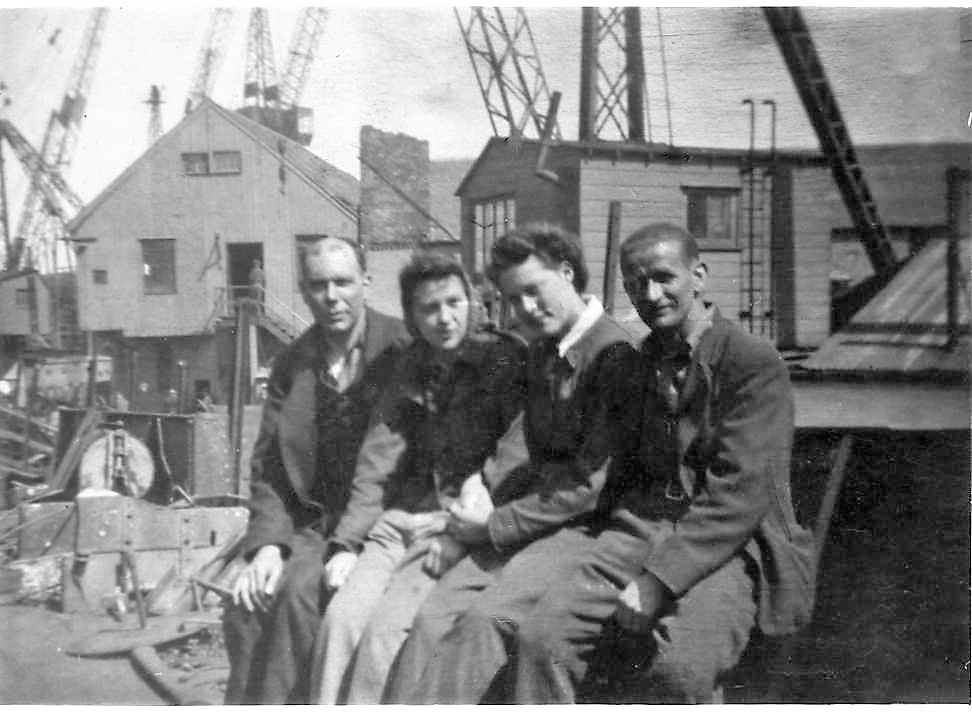

While many of the trades in the boatyard fell into the category of Reserved Occupations, so much labour was required during the war that women were recruited to undertake tasks normally done by men. Women made up about 25% of the boatyard workforce during the war, training to be welders, burners, blacksmiths, plumbers, carpenters and crane drivers (Bailey p. 304).

Working Conditions

Working conditions in the boatyard were dirty: workers went to and from work in their working clothes and washed hands with soft soap that smelt of fish. Noise was a feature too, especially once hand-held hammers gave way to pneumatic operated tools. And there was very little Personal Protective Equipment, particularly alarming when one considers the amount of airborne particles, including asbestos, used to insulate pipes. I remember my experiences working in the dockyard:

When a welder was tack-welding brackets for a cable tray you were installing, it wasn’t unusual for small pieces of molten metal to go down your back, and it didn’t half made you dance! I remember once, standing on a metal girder with my mind on the job, I glanced down at my feet and find my boots have been painted with red lead paint! The painter happened to be painting the girder at the same time - he thought it was funny.

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

Launches

In launching a ship, the timing of the tides is critical, the highest possible tide being required to give the maximum depth on the River Carron. When a ship was launched, the pupils of the local Zetland School, which was next to the boatyard, were allowed out to witness the event.

To slow a ship down during a launch, and to help it negotiate a slight bend in the River Carron, heavy weights were required – either chains or piles of steel plates attached by a steel rope to the ship. I remember:

We watched the launch of the Carway. As it came to the end of the slipway, the cable that was attached to the pile of steel plates parted company. The bow seemed to drop and the ship started rocking from side to side, and with nothing to hold it back it went straight across the river and hit the opposite bank. It then drifted sideways until the bow got stuck on the near bank of the river. The two tugs in attendance tried in vain to free the ship from the bank, then one of the tugs was put out of action by getting its propeller snarled up in some steel rope. The tide was on the turn but the ship was finally pulled around by attaching a steel rope to a winch situated further up the yard. I heard one worker say, “Should have left it there as the Bridge over the River Carron!”

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

The Last Days of the Dockyards

The last ship built by The Grangemouth Dockyard Co. Ltd. was the Irvana, a fishing stern trawler, launched in 1971 and completed in 1972. After the last ship was built, the boatyard concentrated on ship repairs. In 1967 the boatyard had become part of Swan Hunter, and in 1977 Swan Hunter in turn became part of British Shipbuilders. With no new orders forthcoming operations wound up. In 1984 Grangemouth Dockyard Company re-emerged as a private company, but in 1987 that company went into liquidation.

By Bill Smith, Great Place volunteer 2020.