As Scotland’s Garden and Landscape Heritage (SGLH) Chairman I am very proud to present this story about South Bantaskine Estate by Diana Hardstaff, volunteer on the Glorious Gardens team assigned by SGLH to the recording of non-inventory designed landscapes and gardens in the Falkirk area. The Glorious Gardens project was launched in Falkirk in 2015 and was funded by Historic Environment Scotland. This is one of the 16 sites covered by SGLH in this area. A similar project was carried out in the Clyde and Avon Valley, and we are currently planning a third phase, which will focus on sites in East Lothian. For more details, please go to https://www.sglh.org.

Coal Production

South Bantaskine is a story of a wealthy nineteenth century coal family and the gardens they made. Robert Wilson moved his family to South Bantaskine in 1828. He was a coal master and he was preoccupied not only by coal but also the battlefield on which an ancestor Sir John Drummond had fought.

The Wilsons lived cheek by jowl with their working pits. An early 19th century mine map shows the walled garden behind the house, literally next to “coal workings.” A “water mine” drained mine water into a channel that ran next to the tree lined entrance avenue and discharged it further downhill.

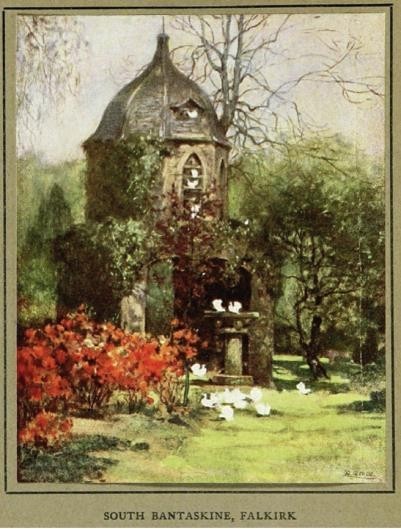

We know a little about the garden at the time. One mine map shows that the square walled garden was divided up by paths and had two entrances. Walled gardens were a relatively common feature of larger houses at the time and provided protection for crops from deer, rabbits and petty thieves. The family also kept doves in an ornate ogee shaped dovecote incorporated into the stables. One surviving photograph shows the estate staff assembled in front of the old stables and dovecot. Some food was stored in an ice house which still exists close to the Union canal.

Remodelling

Around 1860 things changed. Robert’s younger son, John, appears to have inherited the estate on his father's death in 1836 and in 1848 he married Mary Russel, the daughter of one of Falkirk’s legal families. Coal production ceased, and by 1860 the couple had begun to repurpose the estate.

The existing house was demolished and a new gothic-styled house built complete with a large stained glass window depicting Sir John Drummond. The existing stables were demolished, save the ornate central dovecot that was spared and survived until the early 1970s, and new stables were built out of sight of the house. A waste heap was flattened to form a bowling and tennis lawn.

The new house was approached along the former mine track updated by a fashionable six strap estate fence, rhododendrons and trees to give the impression of a country lane. The formal Avenue fell into disrepair. As to be expected, the garden was centred around the house and the walled garden. The Falkirk Herald on the 7th January 1858 reported that the weather had been so mild that

“In the garden of John Wilson esq. South Bantaskine the following flowers are in bloom – Azalea nudiflora, wallflower, polyanthus, marigold, pansy, monthly rose, géant de batailles rose, anemone, Acuba japonica and other plants.”

A cedar tree and yews were planted between the walled garden and house and are still there today. By the end of the century a fashionable conservatory had been erected near the walled garden where there was also a newly acquired greenhouse that overwintered Agave from the “new world.”

Pastels and Colour

The Wilsons had nine children – eight girls and a boy. One daughter, Mary, trained as an artist in Edinburgh and Paris. John Wilson died on the 13th April 1883. Three unmarried daughters, Nell , Mary and Joey lived on in the house long after their father and brother had died and their sisters had left. The estate left them well provided for. Mary developed her career as an artist. She illustrated two books in the early 1900s, Garden Memories and Scottish Gardens using South Bantaskine as inspiration. In Scottish Gardens the author, Sir Herbert Maxwell, wrote a short chapter about the gardens at South Bantaskine.

He wrote: “the gardens of this place rely on the commonest of materials – tulips, hyacinths, narcissus, arabis myosotis and wallflowers in the spring – lupins, roses, posies, pansies and such like in the summer’ and goes on ‘one shrub however deserves notice as evidence of the climatic capabilities…. Rhododendron Thomsoni is one of the most brilliant of a class usually reputed too tender to endure northern winters, has attained a height of eight feet”

Mary drew them all – common or not!

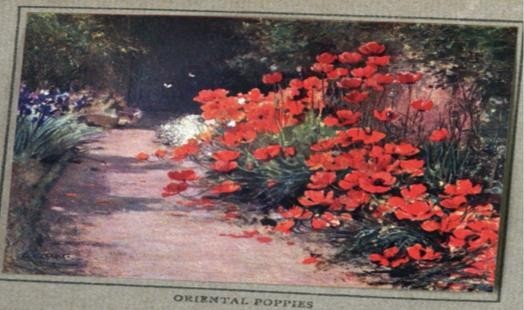

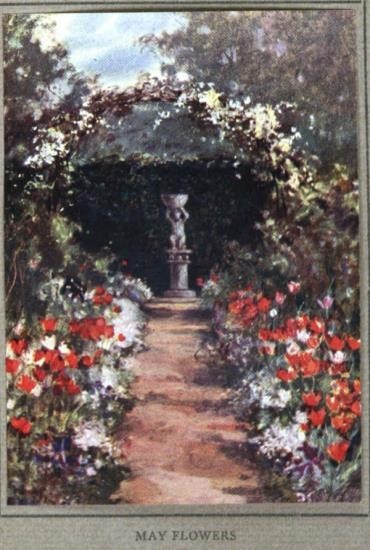

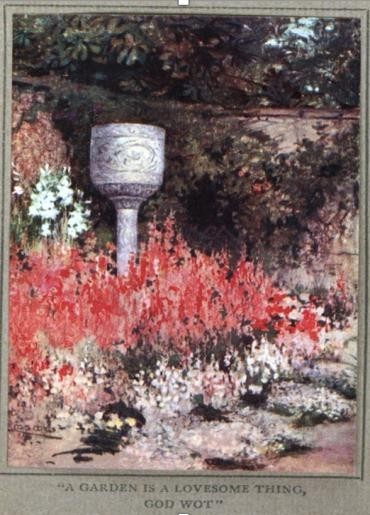

At around the same time another artist, Gertrude Jeykell (1843-1932) was writing about the use of colour in herbaceous borders and Mary’s pastels similarly illustrate various colour themes in the garden such as scarlet poppies and blue iris in “Oriental poppies,” and pink and white blooms on arching stems in the “Phlox border,” red tulips, and orange azaleas close to garden arches.

Mary’s pastels show at least two different urns that provided focal points and several rose clad archways. The Falkirk Herald (1939) reported that in “the flower garden there are artistic displays … with antique ornamental statuary as picturesque decorations.”

She also drew an illustration of the dovecot for A. O. Cooke’s A book of Dovecots published in 1920. Cooke tells us “standing on shaven turf and backed by a wide-spreading cedar, with clumps of rhododendrons and azaleas in full bloom, this South Bantaskine dovecote would be hard to match. And the last needed touch is given by the snowy fantail pigeons that forever flutter round the roof and windows.”

Rock gardens

The cultivation of alpines was popular with Victorians and in 1907 Reginal Farrer’s book My Rock Garden fed the craze. The Wilsons weren’t left behind and developed two rock gardens.

Maxwell tells us that “More ambitious ... is the design which the ladies have undertaken in converting a disused quarry into an alpine garden. It will be a rockwork of Cyclopean scale. A vast vertical cliff of carboniferous sandstone.” In Cooke’s book we learn that the “house itself is not a century old; and the adjoining quarry whence its stone was taken has been turning in to a most charming water-and rock-garden, where a small stone Cupid smiles upon the scene.”

Mary’s illustration of the quarry rock garden shows that a flight of steps led down one side of the quarry to a platform flanked either side by a pair of topiarised trees, the so called “Sentinels” and was laid in fashionable Edwardian crazy paving. Around the pool yellow iris, pink candelabra primulas and flowering hostas grew.

Scotland’s Garden Scheme

The Scotland’s Garden Scheme – the “yellow book” – began in 1931. And once again the Wilson sisters were at the forefront opening their garden from 1932 to 1934 and again in 1939.

The Falkirk Herald reported in 1939: “Then there is the famous rock garden. Fashioned from a disused quarry, this rock garden has come to be regarded as one of the most noteworthy in the country. With its mass of bloom and foliage, in which many varieties of rock plants are to be found this garden has been aptly named a “fairy glen.” The fountains, quaint statues set in restful nooks, the crazy paving and the rustic fascination of this manmade horticultural shrine, all combine to form an idyllic retreat.”

The Decline

After the death of the Wilson sisters, the land was rented out to the Callendar Coal Company Ltd. and after the war the estate passed into the hands of the National Coal Board which duly demolished all the houses on the estate and opened a colliery. And so the story had come full circle. Though the gardens at South Bantaskine have faded away, their memories live on in the pastels and photographs left by the Wilsons.

By Diana Hardstaff, Scotland’s Gardens and Landscape Heritage volunteer.