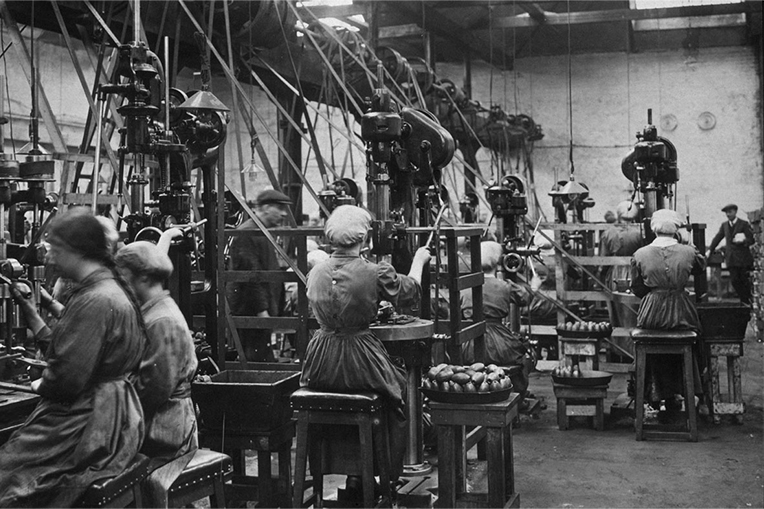

Following the outbreak of the First World War, munitions factories all across the country began recruiting women for their workforce, and the munitions factories in the Falkirk district were no exception. Take a look at these stunning old photographs and read on to find out more!

Cause you got that later on you began to realise that women maybe had a part in everything.

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

How much were women workers paid?

Pay generally differed between factories and the different types of munitions they were producing. In the Falkirk district, women working with heavy shells in the Bainsford and Carron factories tended to make more than the women working with grenades in the Falkirk Foundry. However – regardless of what factory they worked in – women were paid less than their male counterparts. In governmental reports, women are reported to have been more expensive to employ as they had no previous training, and it was therefore considered justifiable to pay them less. This is in spite of the fact that many factory owners reported that employing women led to an increase in the quality of the products being made. Regardless of this wage gap, for many women the money they were earning in the munitions factories was generally more than they would receive in other, more domestic, occupations. Jean Paul’s interview is again another great example of this, as she discusses how she made 17 shillings a week in the factory, compared to the 5 shillings a week she made working as a table-maid in Polmont House. So while the wage gap highlights the inequality female workers faced, it was not an issue that angered many munition workers at the time. You can see women busy at their work in the munitions factory in these amazing images from the Falkirk archives.

After the war

The end of the war saw both the return of men to the factories and the interwar decline of munitions production. With the initial workforce back and a reduction in manufacture, women were replaced in the factories very quickly, leaving some feeling as if they had been thrown out overnight. The response to these changes was mixed: most women were just happy that the war had ended, but others were unhappy at the prospect of returning to the role of stay-at-home wife. The role of women in munitions factories had a lasting impact on society even after the Armistice was signed. In the 1918 Representation of the People Act, women property-owners over the age of thirty were given the right to vote, and the roles women played in the factories were seen as playing a big part in justifying these new rights. This was because women in the factories had ‘proved themselves’ to their country and government. Many of the munitions workers, however, did not meet the property condition required to vote, and would not be enfranchised until later reforms in 1928.

Ultimately, although their time working in the factories was brief, female munitions workers gained knowledge and skills in an industry that they probably would never have been able to experience otherwise.

A dangerous job

Munitions work was high risk, and there were a number of dangers that came with working in the factories. The mechanisms in the factory were running constantly, and were known for dragging anything caught in them into the machine. For women, this was a major risk if they had long hair, and even a few loose strands outside their mob-cap could result in an accident. Munitions worker Margaret Campbell recalls how girls were sometimes even scalped by the machine if enough of their hair got caught in it. Work in the explosives factories was equally – if not more – dangerous, as any accidents involving gunpowder could lead to fatalities. Nobel’s (as in Alfred Nobel) explosive factory in Redding was key to the war effort, employing over 200 women in 1915. Nobel’s factories were famous for producing dynamite, but working with TNT on a daily basis could often lead to TNT poisoning, a side effect of which is the yellowing of skin, giving the women who worked in the factory the nickname ‘yellow canaries’. Most women knew of the health risks of working in such factories, but it did not prevent them in the slightest from doing their part for the war effort.

Why did women work in factories?

Men were forced to join the army because of militray conscription. This resulted in a huge lack of workers in the industry, and women – along with young boys and girls – were the only people left to fill this gap. Many women, however, did not begin work in the factories simply because it was required of them. They felt a strong sense of duty to their country and wanted to help out in any way they could. Working in munitions factories was seen as a key way in which all women could help the war effort. Even at the end of the war, the knowledge that they had helped their country at such a vital point was something that many women remembered for a long time. This is perhaps best exemplified in an oral history interview from 1984, where munitions worker Jean Paul is interviewed about her memories of working at the Falkirk Foundry. When asked about her strongest memory of working in the factory, she states that it was knowing that ‘[she] was doing something to help’.

Following the outbreak of the First World War, munitions factories all across the country began recruiting women for their workforce, and the munitions factories in the Falkirk district were of no exception to this. After conscription was introduced through the 1916 Military Service Act, the number of women in the munitions workforce rocketed, as they went from volunteering to work in the factories, to making up the majority of the workforce. In Falkirk, where ‘heavier class’ iron foundries were located, women made up over half of the wartime workforce. The experiences of these women were very unique, as for many of them it was the first industrial job they ever had.