Angus McIver has been tracking the migration route of a flock of Bean Geese who, since the 1980s, have chosen Slammanan, Falkirk as an annual winter feeding and roosting point. Read on, or listen to sounds of the geese calling, to find out more about this unique aspect of our local natural heritage.

It was nearly an hour after sunset when I heard the sound I had been waiting for during the past hour or so. The wind was westerly force 2/3 but I could hear the calls of the geese coming from some distance. I looked through my binoculars in the fading light, and there they were, a long line of dark silhouettes flying towards me. I tried to count them quickly but found it a difficult task so decided to watch and listen instead. Bean Geese are often thought to be a quiet species compared with other geese but the increasing cacophony of calls on the approach to their roost that night put paid to that. I was in position near Fannyside Lochs in North Lanarkshire but my Bean Geese quarry had flown in from the north east of Garbethill Muir situated approximately 4 miles south-west of Falkirk.

Two species of Bean Goose occur in the UK as winter visitors, the Tundra Bean Goose (a rare straggler), and the Taiga Bean Goose (named after their principle breeding habitats in northern Europe). There is a flock of Taiga Bean Geese which breeds in Sweden and winters regularly on the Slamannan Plateau, in the Falkirk area. This will soon probably become the only flock in the UK, as the only other regular flock, in Norfolk, has recently declined to a handful of birds.

This remarkable migration highlights how rare birds can turn up in odd locations and successfully re-orientate, even on their own.

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

Numbers of Bean Geese in Scotland, mainly wintering in the Ken/Dee marshes in Dumfriesshire, peaked at 400-500 birds in the late 1930s but declined from the mid-1940s, with the last 18 birds there recorded in February 1992. The flock is thought to have gradually changed its preference to the Carron Valley in West Stirlingshire, where the maximum number of Bean Geese recorded was 122 in 1987-88. From the late 1980s, the birds also began to be recorded at Slamannan in the Falkirk District, and eventually the whole flock relocated there, abandoning the Carron Valley entirely. The Slamannan birds now represent the entire wintering population in Scotland. The flock numbered 130-150 birds in the 1990s, peaked at around 300 birds during the mid-2000s, and has since stabilised at about 230 birds. The Taiga Bean Goose is considered a threatened species and is thus a conservation priority in the UK, where it is red-listed and is on the Scottish Biodiversity List. Information on the flock’s provenance, migratory movements, key stop-over sites in Scandinavia, and winter movements on the plateau is therefore urgently required.

The Taiga Bean Geese at Slamannan forage on agricultural grassland by day and roost on nearby water, old peat cuttings and flooded fields at night. On moonlit nights, bright enough for the birds to see potential predators such as foxes, they often continue to feed on the fields. Recently, the flock has begun feeding on oat stubble fields, which is likely to be an important food resource for the newly arrived birds. These geese have been monitored at Slamannan for the past twenty years and, with its key roosting and feeding sites protected by Special Protection Area (SPA) designation, it is important that any other potentially new winter feeding and roosting sites of Bean Geese on the plateau do not go undetected.

Migration between Falkirk and Dalarna County Sweden

It has been a priority to discover the flight paths during the autumn and spring migrations in between the Bean Goose breeding and wintering grounds, as well as the birds’ movements in Scotland. Monitoring these birds has involved collaboration between the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT) and Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH), who caught them using cannon nets in the autumn of 2011 of 2015. The netted birds were aged, sexed and measured, and fitted with identification leg-rings and lightweight numbered neck-collars. Several birds were fitted with a GPS-type collar, so that their movements could be tracked. Similar catches were made in 2012, 2013 and 2015, giving a total of some 40 birds caught and marked, including, in 2015, an adult pair and their three juveniles, all of which were tagged. The information gathered through these methods includes valuable daily updates on the flock’s movements and has enabled conservationists to identify their migration stop-over places in countries across the North Sea.

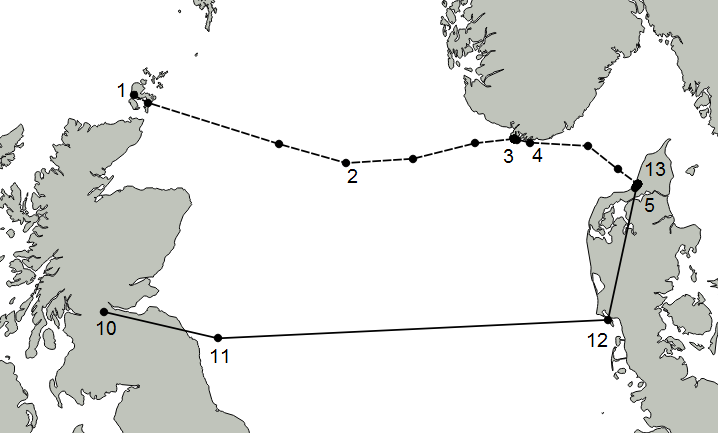

In the spring, the geese fly from Scotland across the North Sea to Pandrup in northern Denmark, where the Slamannan Plateau flock splits up. One cohort flies to Saffle in southern Sweden and the rest fly to the Glomma river system at Akershus northeast of Oslo, in Norway. This flock then stops at Braskereidfoss and then at Rena, before the final flight to the east into Dalarna county, Sweden. The group at Saffle appears to fly directly north from there into Dalarna County. In the autumn, the Saffle group appears to come south into northern Denmark before returning to Slamannan across the North Sea, and the rest of the geese come back through Norway.

The geese appear to use the Forth estuary as a navigational aid as they return to Slamannan in the autumn. Due to harsh weather conditions, things do not always go to plan for the geese, which can end up arriving in the UK anywhere between Aberdeen and Norwich. Regardless of where they come ashore within a few days they arrive at their wintering grounds on the Slamannan plateau.

There is a flock of Taiga Bean Geese which breeds in Sweden and winters regularly on the Slamannan Plateau, in the Falkirk area. This will soon probably become the only flock in the UK.

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

Goose stories

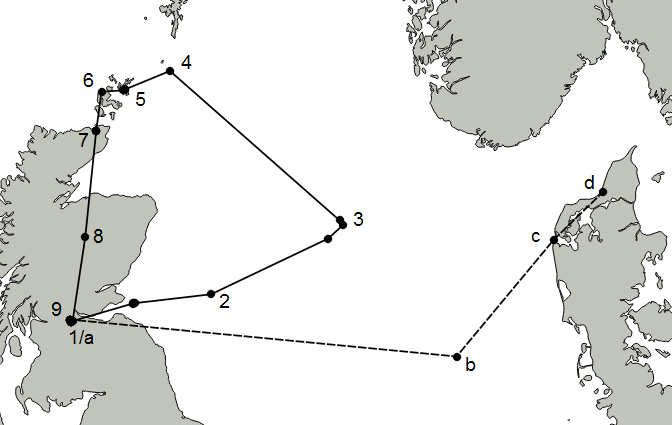

A notable spring migration took place in 2017 and the following note tells the story of several tagged birds. A flock of Bean Geese left Slamannan on the 6th of February and headed out via the Forth estuary towards Denmark. Part of the flock were caught up in a south-easterly gale which pushed them north-westwards towards Fair Isle. Fortunately, these birds managed to divert course and landed in Orkney. The following day, two of these birds flew south, to arrive in Caithness. The next day they flew over the Cairngorms and back to Slamannan. They remained at Slamannan until the 20th of February, when they set off for Denmark again, passing over Berwick-upon-Tweed, Esbjerg, Denmark, and finally arriving at Pandrup to join up with the rest of the flock. One goose, however, decided to stay where he was in Orkney for another week or so before he flew via southern Norway to Pandrup, Denmark, where the rest of the flock regularly stop off on their migration north to Sweden. Another bird (you can see the different routes mapped out) followed the original trajectory of the geese that managed to avoid the gale force winds and land in Denmark. These remarkable migration patterns highlights how rare birds can turn up in odd locations and successfully re-orientate, even on their own. It confirms too, that birds once displaced by a storm event can head back to their original starting location and try again.

By Angus McIver.