James Bruce esq. of Kinnaird was an author, explorer and academic freemason (Dalivalle). In 1785, he commissioned the Bruce Obelisk, a free standing, cast iron memorial to his loved ones. It currently sits in the grounds of the Larbert Old Kirkyard. Local researchers Geoff Bailey and Duncan Comrie have investigated the obelisk in detail: Comrie in his unpublished article “Discovering James Bruce: A Falkirk Made Friend” (2020) and Bailey in “The Bruce Monument at Larbert” (Calatria Autumn 2013). This is an introduction, drawing on their work, to this ornate monument.

A Colourful Past

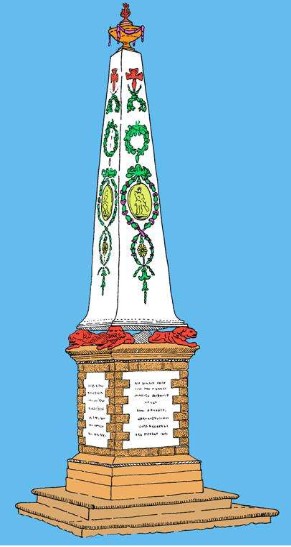

It is important to note that the obelisk as it appears today is very different from how it would have appeared in Bruce’s time. First of all, the obelisk is currently located in the car park of the Larbert Old Kirkyard. This is a far cry from the prominently positioned and landscaped area (above a burial vault) further up the hill where it was originally situated. Secondly, Bailey discovered that the obelisk was designed to be brightly painted (see his illustration below). A combination of time, and well-meaning but now questionable conservation attempts, have changed the look of the obelisk significantly. Today the obelisk is a rusted red colour and looks much simpler than the original design. Nevertheless, the obelisk as it stands today is still visually striking.

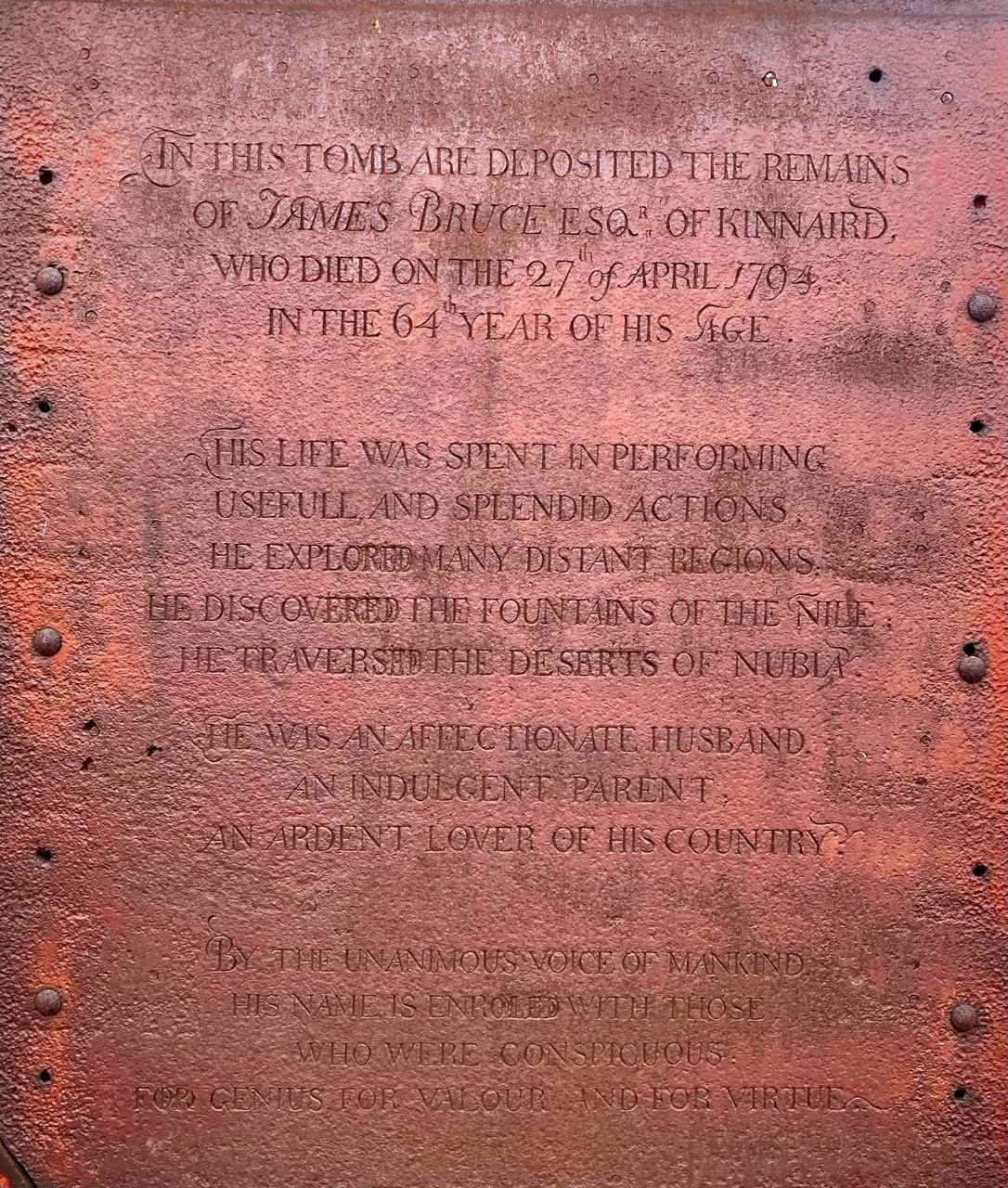

One of the first things you notice when you look at the obelisk are the inscribed cast iron panels on three sides. The first panel is dedicated to Mary Dundas (d. 1785), the second wife of James Bruce, and their son Robert Bruce (d. 1778.) The second side is dedicated to Mary Elizabeth Cumming Bruce (d. 1875.) the granddaughter of James Bruce, and her husband Charles Lennox Cumming Bruce (d. 1875.) The final panel displays an epitaph to Bruce himself.

Family records, coupled with assumptions we can make based on the intricacies, scale and novelty of the design of the obelisk, reveal that Bruce and his family were relatively wealthy and held a high social position in the 18th century. Bruce was able to have a great deal of his adventures due to the Carron Company. The firm opened in 1759, adjacent to land owned by Bruce’s family, and paid the family to mine coal assets. As Comrie wrote, “without their contribution Bruce would have had to cool his ambitions as an explorer” (p.2).

The Ethiopian Aksum Empire

It was this social and financial position that allowed Bruce to follow his passions, travel the world, conduct research, learn languages and write about his adventures. He spent time in Ethiopia, following instructions from King George III to research and record details of antiquities he found. He returned with depictions of many items, including a sketch of the “Obelisk of Aksum” (Dalivalle). This monument was an example of the “stele” that marked the tombs of ancient Ethiopian royalty. These tall, hollow, stone structures are prevalent in areas that were part of the Aksumite Empire (see below).

The influence of Aksumite obelisks on Bruce’s choice of design for his family memorial is clear when the two styles are compared. Interestingly it was the Carron Company that were commissioned by Bruce to create the memorial. Comrie explains that the creation of the obelisk would have been “an expensive and technically difficult project” (p.1). Cast iron allowed for greater intricacy in the design, compared to a carved stone monument. It seems that it was the novelties of design, coupled with the innovative use of cast iron for a standing monument, that complicated conservation attempts. Bruce (or likely the draughtsman who translated Bruce’s idea into a workable plan) drew from many other styles and periods in the obelisk’s design.

This can most clearly be seen in the decoration on the obelisk, which includes elaborate plaques, symbolic depictions of classical Greek figures, an everlasting lamp, festoons, pendants and elephants. Four solid cast iron lions are a particularly prominent part of the design, and this is notable because lions are a symbol associated with royalty in Britain and in Ethiopia (Dalivalle).

Disrepair and Revival

The obelisk appears to have sat relatively unchanged until the late 19th century. Bailey explains that the site surrounding the crypt was maintained until around 1890. At some point around that time the obelisk was allowed to sink into the landscape. By 1902 it had “deteriorated to a state of near collapse” (Bailey p.6). An article in the Falkirk Herald (September 1902) explained that the tomb of “Abyssinian traveller” James Bruce was “in a lamentable state of decay and disrepair” (Falkirk Herald 1902 in Bailey p.6).

In 1908 a committee was set up to bring the obelisk back to life. Bailey records that the group was mostly “concerned that the fame of James Bruce…. continue to be promulgated” (p.8). This unfortunately meant that they were not that interested in the innovative use of cast iron. The monument was evaluated, and it was decided that it could not be conserved. As such, a thoroughly practical solution was proposed by the committee – a new memorial would be created from granite.

A lack of funding meant that the committee’s plan was stymied and they decided to restore the obelisk after all. The Carron Company completed the restoration work but they were limited in what they could do due to the condition of the obelisk. The larger panels are recorded as having been fractured, and various smaller parts were corroded to the extent that they had to be copied, and then replaced. Other quite substantial structural additions and changes were completed, but as Bailey records “the changes produced little comment at the time” (p.9).

The Traveller’s Obelisk Travels

The monument was once again conserved in the 1980s. During this restoration the previous restorations attempts were consolidated, however the urn finial was lost. It was after the journey back from the Torwood Foundry of Jones and Campbell in 1993 that the memorial was deposited in its current position in the Larbert Old Kirkyard car park, as the delivery vehicle did not have a crane arm long enough to position it back in the original site.

It was this series of events that resulted in the simplified form of the obelisk. If you get a chance to visit the memorial you should look out for the panel dedicated to Bruce. One section of his epitaph reads:

HIS LIFE WAS SPENT PERFORMING

USEFULL, AND SPLENDID ACTIONS

HE EXPLORED MANY DISTANT REGIONS

HE DISCOVERED THE FOUNTAINS OF THE NILE

HE TRAVERSED THE DESERTS OF NUBIA.

These few lines give us a sense of the image Bruce had cultivated throughout his life. It appears he wanted to be remembered as an explorer. Despite the monument having been moved, damaged and significantly restored over the years, many of the key themes of Bruce’s life are still represented by the material and form of the obelisk.

By Rowan Berry, Heritage, Engagement and Interpretation intern at Falkirk Community Trust, and Hidden Heritage Online: Ancient Falkirk volunteer.