The remains of the Antonine Wall, which marked the northern border of the Roman Empire, is the largest relic of the Roman occupation of Scotland and has a fascinating history.

The Antonine Wall was built between AD142 and AD160, when it was abandoned. The wall was 37 miles long from the River Forth to the River Clyde and is a UNESCO World Heritage site. Remains of the Antonine Wall in the greater Falkirk district can be seen from the Kinneil estate in the east to Seabeggs in the west, including sites at Rough Castle, Tamfourhill in Camelon, in the grounds of Callender House (restored with a permanent exhibition on local history) in Callendar Park, and Polmont Wood. Not a lot remains visible of the Antonine Wall today. Unlike Hadrian’s Wall in Northern England, it was not built of stone but was made up of a ditch and with embankments on either side. The wall was 39 miles long with 19 forts to provide shelter for the troops patrolling and looking for trouble from the Caledonians. Imagine you are standing on top of a turf mound looking north. In front of you is a steep sided ditch, then another mound then the land slopes down to a flat plain, all of which would have made it easy for the Romans to see their enemies approaching, and difficult for the Caledonians to attack.

Roman soldiers didn’t just fight, they built aqueducts, roads, amphitheatres and other structures in stone and turf.

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

Quintus Lollius Urbicus

Now imagine you come from a small village on the fringes of the Sahara desert, in what is present day Algeria. Your name is Urbicus and you go into the army. Roman soldiers didn’t just fight, they built aqueducts, roads, amphitheatres and other structures in stone and turf. When the new Emperor Antoninus Pius wanted a wall built in southern Caledonia to subdue the northern tribes he sent Quintus Lollius Urbicus. Construction on this new wall began just under 20 years after Hadrian’s Wall was completed between the Forth and Clyde estuaries. Urbicus, by then the Governor of Britannia, began by establishing a Roman port at Carriden, just east of Bo’ness. The Romans didn’t stay long. The wall was built starting in 142 AD and the Romans left around 164 AD. Urbicus came all the way from the Sahara desert to stand here looking at those same Ochil Hills we see today. Quintus Lollius Urbicus, Prefect of Rome, Berber from the African Frontier of the Roman Empire, gave us the Antonine Wall, and almost no-one has ever heard of him!

The Antonine Wall at Kinneil: Forts and Slabs

There were several small forts, or “fortlets,” built along the Antonine Wall. This wall was the most northern boundary of the Roman Empire and a truly remarkable example of defence against the locals. In the year 142 AD the Second Roman Legion, the Augusta, came to this place to build a section of what has been described as the most complex and highly developed of all the frontiers. They left a “distance slab” to commemorate their efforts. The original “Bridgeness slab,” which is considered the best preserved Scottish slab, is displayed at the National Museum of Scotland, while a replica can be found at Kinningars Park, in Bridgeness, Bo’ness.

The Fortlet at Kinneil

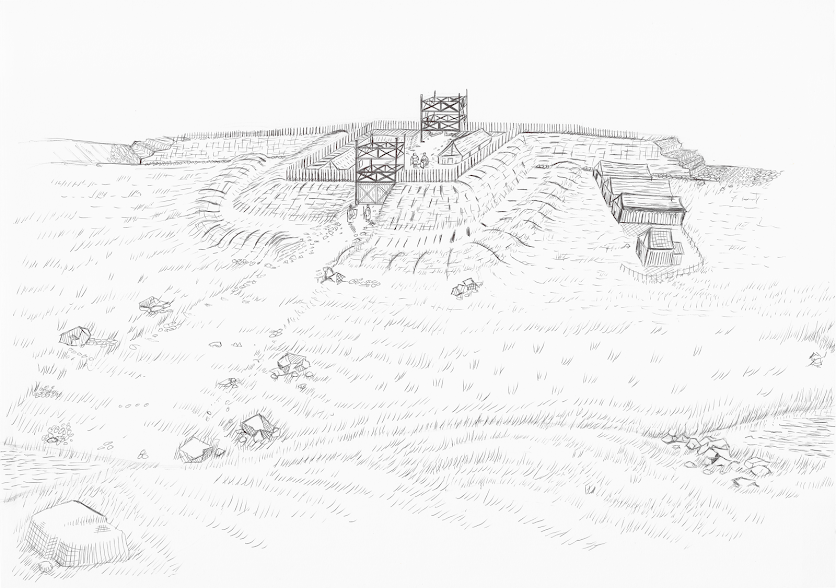

The wall, or rampart, created by the Second Legion at Kinneil, was around four and a half metres wide. It was built of clay and earth, on a stone foundation and was perhaps three metres high. There may have been a wooden walkway and parapet on top of the rampart, but no one knows as wood rots away over time. To attack the fortlet would have been a daring task since you didn’t just need to scale the rampart, you would have had to climb over an exposed outer mound, scramble down into a ditch around four metres deep and twelve metres wide through thorn bushes, clamber back out of the ditch, then cross a further exposed stretch studded with defensive pits, before scaling the rampart itself!

By then, Roman troops would have sallied out of the fortlet. You would be attacked from all sides and pinned between the rampart and the ditch. Along the top of the wall, there would have been observation points, and a road (the “Military Way”) ran behind the wall. Once you were spotted, re-inforcements could be rushed from nearby forts and fortlets. It would have been quite a challenge for anynone who wanted to attack the Romans here.

The Antonine Wall at Rough Castle

The Roman Fort at Rough Castle is one of the second smallest of the 16 known forts on the Antonine Wall, but it’s also one of the best preserved, and well worth a visit. Here you can see the tallest surviving section of rampart, a section of the “Military Way,” which ran the length of the wall, defensive lilia pits (full of deadly stakes), fort and annexe defences, and multiple ditches and gateways. This fort offers the most spectacular and memorable views of the surviving Roman remains, and although the site is grassed over, you get a vivid impression of what a Roman frontier defence must have been like 2000 years ago.

By Diane Cherry and the Hidden Heritage group.