Find out what life was like working in the moulding shop at R&A Main, Camelon, and how the molten metal was shaped. Sandy McGill recalls being apprenticed in the moulding shop at the age of fifteen.

Ned’s arm was so calloused with scar tissue from the flying sparks of molten metal that not only was I unable to stick the pin into him, it actually bent under the pressure I was applying.

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

The formula for filling the furnaces was complicated and my memory is hazy, but it consisted of a specific amount of the pig iron cast from the previous day’s pour, coupled with other scrap metal and a variety of very specific sands. The furnace was plugged at the base where the molten metal was to be drawn off. Then, having been lined, it would be filled with the requisite amount of materials and made ready for firing up for pouring the following day, usually mid to late afternoon.

The man responsible for the furnace was the Furnaceman. In my time that was Ned. I have no recollection of what Ned was like apart from a vivid memory of being given a pin and told to stick it in Ned’s outstretched arm. Ned’s arm was so calloused with scar tissue from the flying sparks of molten metal that not only was I unable to stick the pin into him, it actually bent under the pressure I was applying.

While all of this was going on the “moulders” would be plying their trade on the shop floor. The shop floor was laid out in rows with each moulder occupying one row. They would work in pairs. The floor was sand, a very specific sand which compressed to form a solid enough material to retain the molten metal. You could identify a moulder immediately by his stance and gait. The nature of the work left the men (for they were all men) bow legged and stooped almost to the extent that their torsos were horizontal.

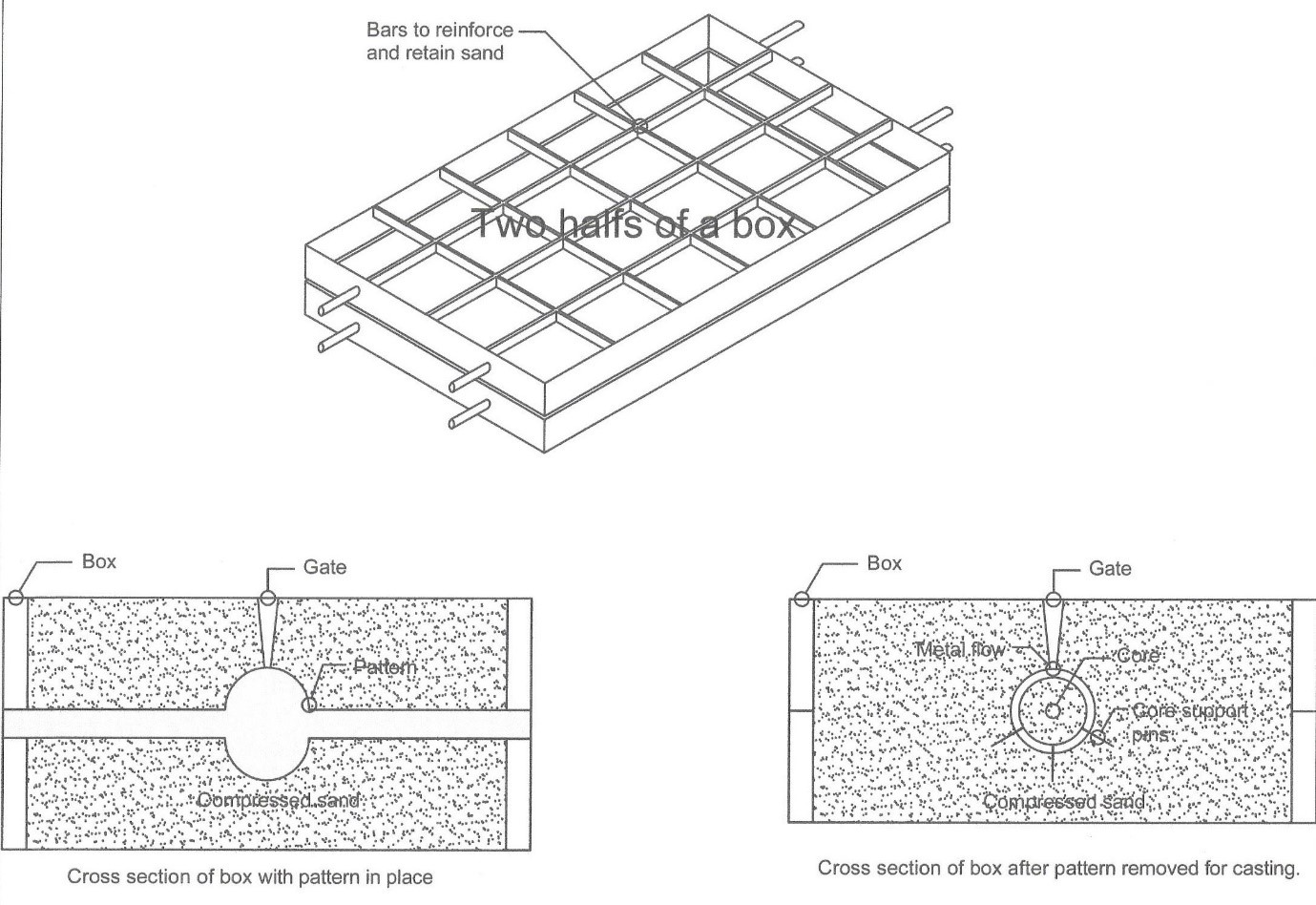

One half of a “box” was cast iron and had sides and a grid of reinforcing retaining bars along the top, with two protruding handles at each end. The box would be laid on the ground and a pattern (also cast iron) would be laid on top. The other half of the box would then be placed on top of the pattern and the whole locked together. The sand would be shovelled into the top part and rammed hard and flush with the top of the box. The box would then be turned over and the procedure repeated. At this point a conical “gate” would be pushed into the sand until it touched the “pattern” and then it would be removed. This, like a garden dibble, would provide the hole through which the molten metal would fill the mould.

Consequently, at this time “cores” would be inserted into the mould. These were baked sand pieces that were the exact shape of the empty space in the burner. They would be very carefully placed with spacers (nail-like things pushed into the mould) so that there was a space all round of equal thickness through which the molten metal would flow.

At this point the box would be taken apart and the pattern removed. Most of what was being made here were burners for gas cookers which were of course hollow.

You could identify a moulder immediately by his stance and gait. The nature of the work left the men (for they were all men) bow legged and stooped almost to the extent that their torsos were horizontal.

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

The molten metal would cause the cores to disintegrate but not before it had assumed its solid state. Each row would have maybe 20-30 boxes like this made progressively using the same pattern from about 5 or 6 in the morning until about lunch time. The men would be stripped to the waist, and probably wore nothing more than underpants (if at all), a pair of trousers and a pair of tackity boots. They would congregate at lunch time on a plank of wood spanning two piles of bricks, and have lunch from their tin lunch box, and tea from an enamelled cup or billy can.

After lunch the furnace would be breached and the moulders would queue up behind Ned the Furnaceman with their ladles at the ready. The ladles consisted of a steel bowl about the size of a soup pan with a long steel handle, maybe about four feet long. Once the furnace was breached the molten contents would be allowed to run into a large steel receptacle about 4-5 feet in diameter and about 3 feet deep. It had two opposing pivot lugs on the side slightly above half way and this was suspended from a rail above.

This receptacle (it must have had a name which I cannot recall) would then be turned by a wheel at the side to allow the molten metal to pour from a forward lip into each moulder’s ladle in turn. The moulder would then walk to his row carrying this ladle full of molten metal and pour the metal into the gates of each box in his row. He would make a few returns to the furnace to complete this task during which time the temperature was overwhelming and the atmosphere heavy with steam and sand.

Then the moulders were done for the day. Each moulder would employ an “emptier” whose job it was to break open the moulds and lay the resultant castings aside for inspection having broken the “gates” off the burners. The emptier would then tidy the row and clean and set up the boxes for the following day.

This was where I came in! After all the boxes were emptied and their cargo placed in a line at the end of the row, Mr. Black and I would inspect each pile, and either reject or accept what lay there. All the accepted items were recorded against the name of the moulder responsible and he would be reimbursed accordingly. He would not be paid for rejected work. This was called “Piece Work”. It was theoretically possible for a man to toil for a whole day in these inhumane conditions and receive nothing in return. The castings would then make their way to the finishing shop where the rough edges were ground off before being sent for enamelling.

By Sandy McGill.