Learn all about the different machines used to make toffee and take a glimpse into how things worked in McCowan’s toffee factory…

McCowan’s toffee factory made a lot of varied products. From their tangy WHAM bars to the infamously hard-to-get-out-of-carpets Irn-Bru Chews, if it was chewy and got stuck in your teeth, the chances were it was made in the Stenhousemuir factory. The varied flavours and exciting packaging came later, of course. When McCowan’s was first founded by Andrew McCowan, the company sold carbonated drinks and sweets made in his own kitchen. The drinks weren’t very successful, which, given that the giant Barr’s Drinks factory was running just down the road in Falkirk, probably wasn’t surprising. The sweets, however, were. Especially the toffee.

Preparing Toffee

The great thing about selling toffee was how simple it was to produce. The basic ingredients were easy to come by, even for an ex-herdsman in Stenhousemuir. Sugar, butter, and cream could be bought reasonably cheaply. Possibly the greatest piece of genius about selling toffee is that a little goes a long way.

“If it took a child ten minutes to unstick their teeth from their “Coo Candy,” the sweet itself didn’t need to be too big, which meant that one batch of toffee could be sold in many small pieces.”

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

Although by this point McCowan’s had at least thirty-five individual products, the company never aimed to make big-money items. They had always aimed and marketed their products at children and that meant prices and products children could afford. Toffee and chewy products are cheap to make, so that was what they did.

When Nestlé took over, they expanded McCowan’s product list, introducing the famous WHAM bar (see our story “Remembering the Wham Bar”). The factory was adjusted to make room for such products. When the factory closed in 2011 it was set up for the production of mint imperials, WHAM bars, and, of course, toffee.

Production in the early days would have been quite simple. Large copper pans would have been common, as jam making and preserving fruit would have been very commonplace. To make toffee, the ingredients are melted together to a high temperature. According to the BBC’s “Chewy Toffee Recipe” that temperature is 125 degrees celsius. Too cold, and the sugar won’t have melted properly. Too hot and it will burn the sugar and waste the entire pot. In modern times achieving that temperature is quite simple, as a cooking thermometer can tell you the instant you reach the right temperature. You can see this in our toffee making video, also part of this Hidden Heritage Online collection. When McCowan’s was starting in 1900, it is unlikely that they would have had access to a cooking thermometer. So, there were two options for testing the temperature.

The first, in Hannah Glasse’s book “The Compleat Confectioner”, printed in 1770, had the cook keep a basin of water next to their cooking pot. Quickly, a finger was dipped into the water, then into the boiling sugar, then back into the basin. If the sugar goes “Crack hard” the toffee is cooked.

It should be obvious why this is a bad idea and not to be tried at home.

The other option was to drip some of the mixture into a glass of water. If it immediately hardened in the water, it was done.

Once the mixture was up to temperature, it was poured out into a tray and left to cool until soft. Then it was scored into shapes, left to cool again and sliced into pieces, wrapped and sold alongside lemonade.

Very quickly the sale of this toffee was supporting Andrew McCowan’s family and he expanded from his kitchen, buying a sweet shop on Church Street in Stenhousemuir.

Toffee Production Machinery

As demand increased for the popular chewy toffee, as well as their other confectionary products, production methods needed to change to keep up. It is likely that it is around this time that McCowan purchased the toffee cutting machine that now lives in the Falkirk Archives (Fig. 1). Produced by Brierley, Collier and Hartley Ltd, in Yorkshire, this hand cranked machine took a strip of cooled but still malleable toffee and snapped it into small round shapes, like the Penny Toffees that McCowan’s sold, mostly to children. This sped up production and allowed sales to increase. Interestingly, Brierley, Collier and Hartley Ltd. still make food production equipment, although they now trade under the name of BCH Ltd.

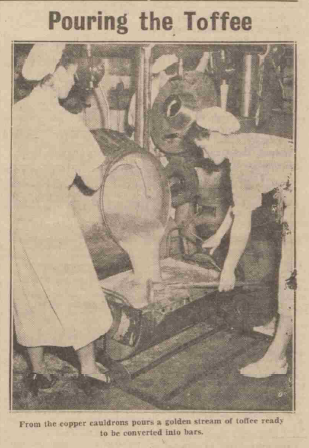

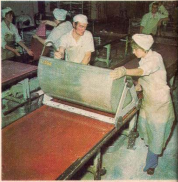

In 1924, Andrew McCowan opened the modern factory. Although a fire in the early days did disrupt business for some time, the factory had increased automation and all of the latest machinery. Some of the machinery remained recognisable. Fig. 2 shows the copper toffee pans, used up until the factory closed. The Falkirk Herald reported that these pans stirred and heated the molten mixture with silver paddles, to ensure that nothing stuck to the pans. In the same article, written in December of 1954, the readers were given a tour of the McCowan’s Factory, which, by that point, was known for making all of Stenhousemuir smell like cooking toffee. Once the toffee had cooked, it was poured out on long cooling tables, sixty-six feet long (Fig. 3). Each of these tables was water cooled, to ensure that the metal didn’t retain heat. The toffee was smoothed out to prevent bubbles and lumps by the factory staff using large paddles and an overhead press. Once cooled, it was sliced and packaged. This production method is still used today by smaller scale confectionary companies. In the USA, Laurie and Sons use an almost identical system for their own toffees, and they are a modern company started in the 2000s.

Wrapping Up

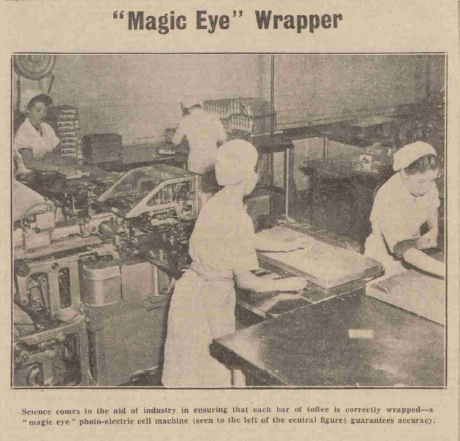

When the factory first opened, the packaging would have been done by hand, but, as the Falkirk Herald reported, times had changed by 1954. To the company’s great pride, they now had an automated wrapping machine which used, according to the Herald, a “magic eye” to wrap the bars (Fig. 4). In more modern parlance, this is a photo-electric cell which is used to detect when a sweet is in the right position to be wrapped by the packaging. The wrapping itself is held on a large steel reel, like Christmas wrapping paper (Fig. 5). You can see the pictures of the factory when it closed with the modern machines shown below (Fig. 6).

Toffee was still, in the 1950’s, McCowan’s main product. When the war broke out in 1939, sugar rationing became a major problem for McCowan’s and, although the war ended in 1945, sugar rationing continued until 1953. Toffee was considered a priority, because of its cheap price and simple production method. Low prices were a theme that continued even after the company was sold to Nestlé in 1959. When interviewed by Scots Magazine in the seventies, managing director Kenneth Taster explained:

“If a child with ten pence goes into a sweetie shop he will spend the first five pence on a luxury item which will not be McCowan’s. He will then spend the next three pence on a semi-luxury item which may be McCowan’s. Now they only have two pence left. It has to be working-class stuff from here on – and that’s where we really come into our own.”

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

By Ely Blyth, Hidden Heritage: McCowan's and Stenhouosemuir volunteer.