One cannot discuss the history of heavy industry in Falkirk without mentioning the name John Gilchrist Stein.

Stein

Born in 1862 to a family whose brick business had already achieved international success, Stein learned a great deal about the industry from a very young age. In 1887, aged 24, Stein purchased a mining lease and acquired the rights to mine fireclay on two acres of land in High Bonnybridge, which held some of the richest clay seams in Europe.

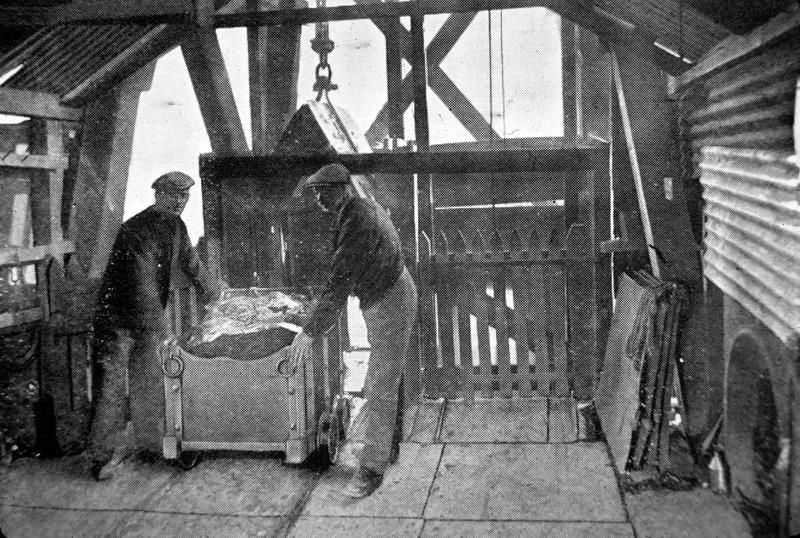

By 1888, he had established mines, had the plant built, and the first kiln was ready to go. Thus began a booming business venture, which expanded to Denny (1892), Castlecary (1899) and Whitecross (1928). You can see two men at the Castlecary mine transporting clay from the mine to the surface using a hoist system, in 1924, below.

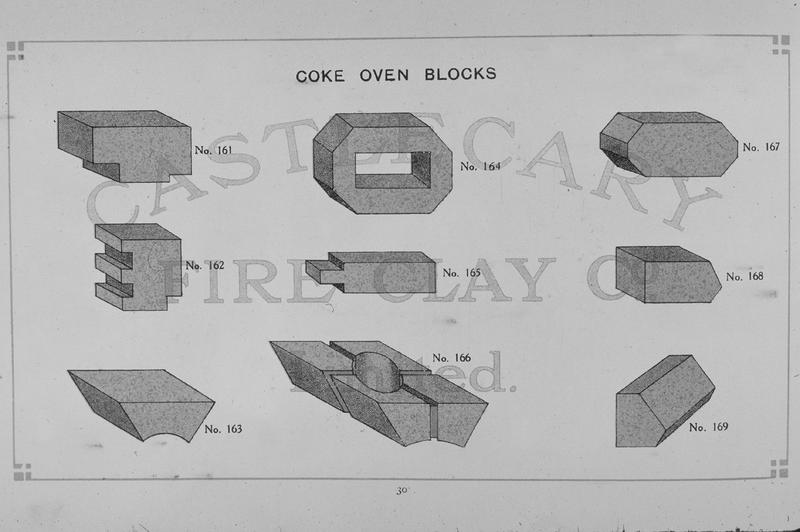

Stein’s products made their way across the globe from Australia to Jamaica where they can still be seen today. Stein bricks were frequently exported to commonwealth countries, as many early industrial nations required firebrick to manufacture things, like iron, steel and glass. In Canada, firebrick was an essential material for building houses, as it could withstand severe winters.

In the late twentieth century, both the international and domestic market for Stein’s product diminished. The growth of global industry replaced the necessity to import firebrick from Scotland and the declining iron industry led to a reduced demand for refractory bricks. John Gilchrist Stein died in 1927. The Stein family continued to be involved in managing the refractories up until the very end.

Manuel Works, 1928 - 2001

Though each of Stein’s ventures was highly lucrative, one of these refractories was particularly integral to the growth of his global empire. Following the success of Bonnybridge, Denny and Castlecary, Stein continued to seek opportunities to expand the business.

On Christmas Day in 1923, rich seams of high alumina clay were discovered near Linlithgow, prompting the construction of a new plant which became famous for its “Nettle” brand bricks. The plant was called Manuel Works, taking its name from the nearby Manuel Nunnery, an ancient ruin by the River Avon.

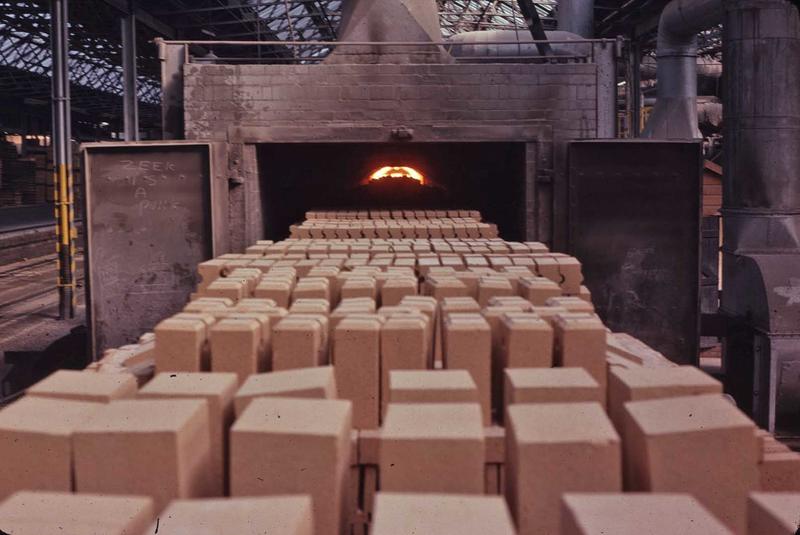

This plant took the company to new heights using the first American harrop tunnel kiln of its kind in the UK. These new kilns were able to fire bricks at a temperature of over 1700°C, boosting production just in time for World War Two.

Manuel Works became the largest brick manufacturing plant in Europe, and second largest in the world, after A. P. Green Refractories in Mexico, Missouri. Contracts were established with over 120 different countries and production peaked at 200,000 tonnes of brick per year. By the 1970s the plant employed 1,200 skilled workers from the Falkirk district. Generations of families were employed at Manuel Works, contributing to the firm’s international success.

The photographs below, taken at Manuel Works in 1979, show bricks entering a harrop tunnel kiln, a pattern maker, and an exterior view of the Manuel Mine.

In 2001, the Manuel Works was the last of the four refractories to close down. In its final days, employees paid homage to this once remarkable keystone of the Falkirk district, by imprinting two simple words on one of the last bricks: The End.

By Paige Foley, Hidden Heritage Online: Ancient Falkirk volunteer and Great Place Digital Heritage Placement.