James Watt is famous for his inventions, but few know about his connections to the transatlantic slave trade…

Watt, Steam Engines, and Kinneil Cottage

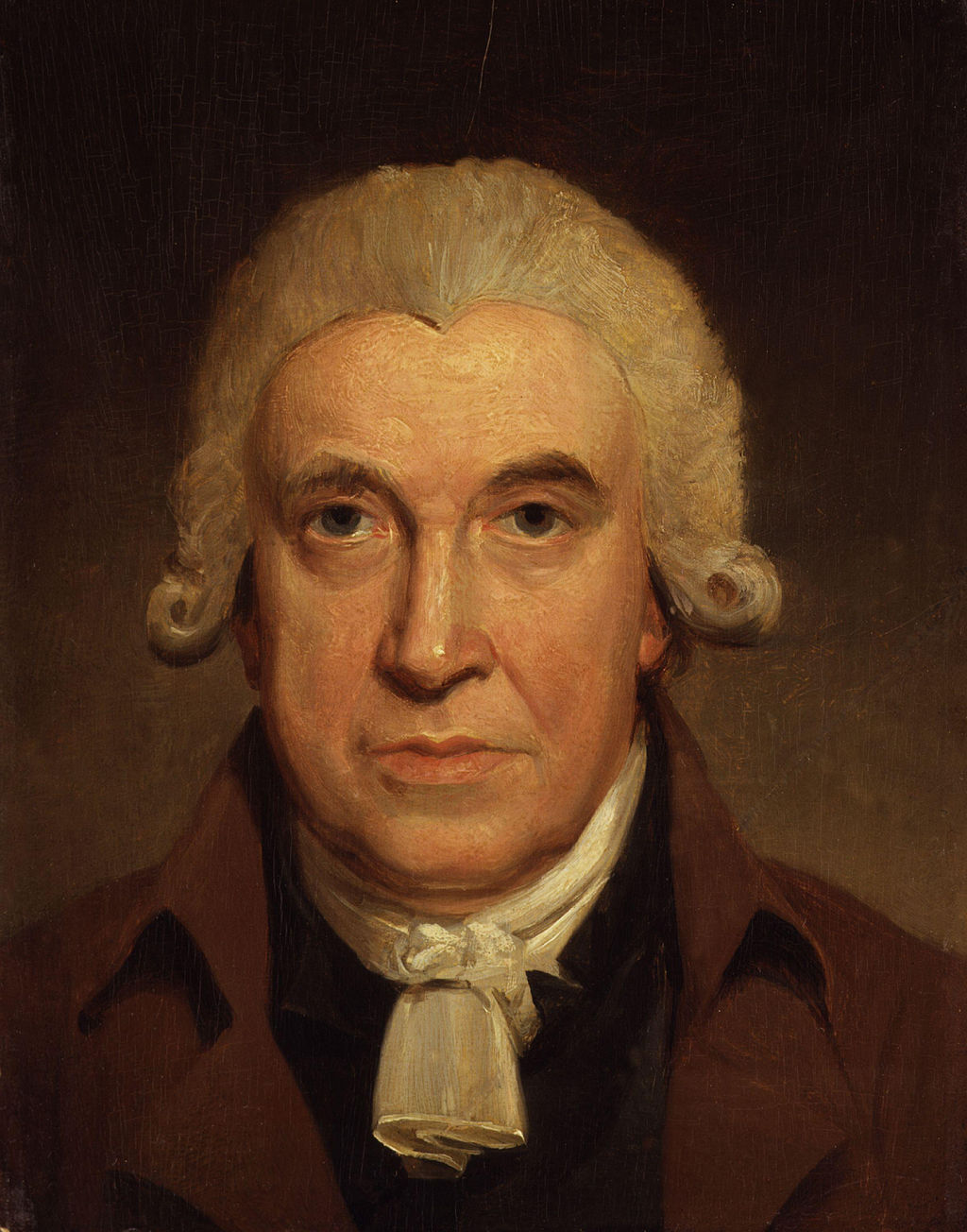

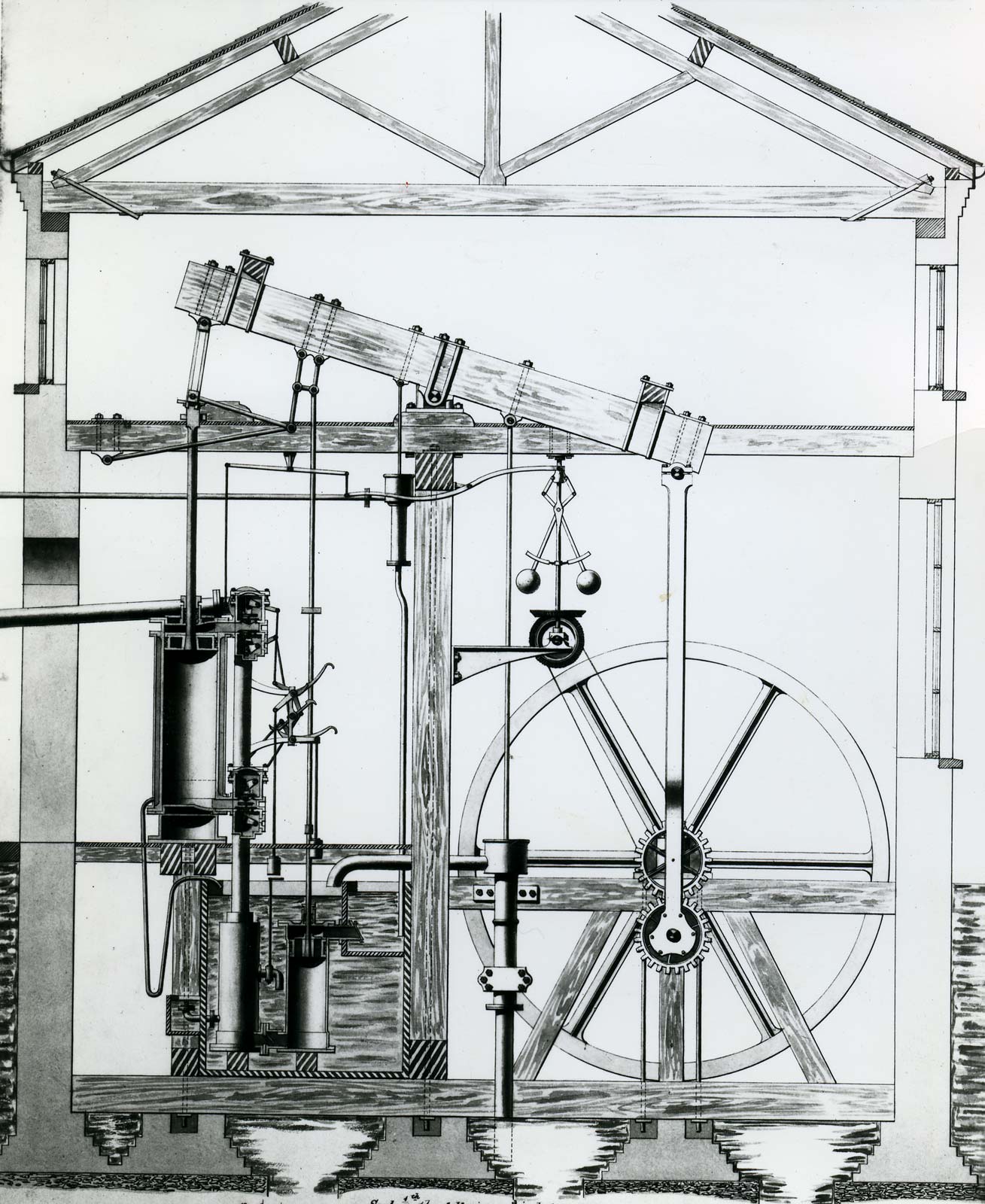

James Watt (1736-1819) is a famous Scottish inventor and engineer, whose steam engine success is famed for contributing substantially to the industrial revolution (Kingsford, 1999). Originally from Greenock, Watt had a keen interest in mathematics, and eventually opened his own business in Glasgow which made and repaired mathematical instruments, before eventually moving on to start another business venture inventing and selling steam engines. Contrary to popular belief, Watt was not the inventor of the first ever steam engine (the Newcomen steam engine invented in 1712), but his success is inextricably linked to it.

During his time in Glasgow, Watt became fascinated with the waste of steam whilst repairing a Newcomen steam engine (Kingsford, 1999) and this ultimately led him down the path to the work he is revered for today: the invention of the Watt steam engine. While working on his plans and experiments for his steam engine, Watt undertook much of his work in his workshop in what is now known as Kinneil cottage, in the Bo’ness area of greater Falkirk. The cottage stands today in the Kinneil estate, and is unique as it is the only surviving building in Scotland which can be directly linked to James Watt (Clark, 2020). This monument is unique in its direct link with Watt, but there are several statues and monuments all around the UK which are dedicated to celebrating Watt’s achievments in the 18th century.

James Watt: Slave Trader?

Whilst it is clear that there is much to thank Watt for regarding his inventions, do we really know everything about the man himself? If asked what they know about James Watt, many people will mention inventions, the steam engine, or statues and monuments which feature Watt. Almost none will know that he was involved in the trade of enslaved people. During the recent global conversation regarding Black Lives Matter, James Watt was publicly added to a list of celebrated historic figures whose names have connections with transatlantic slavery (Mullen, 2020). There has been a surge of research into Scotland’s role in slavery in recent years, and there is a good deal of evidence in the Birmingham Soho archives which indicate Watt’s direct involvement in the trade. One such piece of evidence which has been used in newspaper articles (Leask, 2020) and research papers (Mullen, 2020) is a receipt for the clothing costs of a black boy named Frederick. It has now been established that this boy was brought to Glasgow by Watts’ brother John, with the intention of being delivered to Lady Spynie at Broody House (Mullen, 2020). During this time there is an additional letter addressed to James Watt from James Brodie, which asks for “an account of everything the boy has cost you since his arrival in Greenock”(Mullen, 2020). Such evidence clearly implicates Watt in the slave trade. However it should be noted that the evidence clearly states that it was John Watt who brought the boy to Greenock, and there are also records which show that John Watt drowned shortly afterward, and his estate passed to his brother James. So was James Watt actively involved in the trade of enslaved people or was he only connected to it through his inheritance?

March 17th 1762

Directed to ye Care of Mr John Warrand Merht in ye Salt Market Glasgow to be forwarded to Lady Spynie at Broody House ’

On reverse, “List of Cloths for Black Boy March 1762”

Fridrick The Black Boy Cloths

1 big blew Coat 1 Coat & waist Coat & Britchess

2 pair Stockings & 1 pair Shoes

three check Shirts

a black Gravat & pocket Handkerchefe

a hate & woset keap.

(James Watt, 1762)

Watt Engines: Funded by the Slave Trade for the Slave Trade?

Much of the recent research and publications surrounding the matter argue that Watt’s success was directly linked to the trade of enslaved people. In 1775, Watt went into partnership with English manufacturer and engineer Matthew Boulton, and together they accelerated the production and widespread use of Watt’s steam engine. Watt came from a family of merchants, who undoubtedly profited from the trade of slave-produced goods (University of Glasgow). Boulton came from a metal manufacturing background, and his wealth was a direct result of expansion of the family business in Soho. Historians argue that the accelerated production and widespread use of the Watt steam engine was underpinned by the slave trade profits which both Watt and Boulton benefitted from. In addition to being funded by slave trade profits, there is evidence to suggest that the engines were later used in sugar plantations owned by slave traders. Evidence in the Birmingham Soho archives show known slave traders writing to Watt and Boulton, requesting that they build steam engines to use in Trinidad sugar plantations. One such letter states that the King of Spain “granted a loan of a million Dollars to the Inhabitants of Trinidad for the purpose of erecting Sugar Works & purchase of Slaves…” (Dawson, 1790). In fact, there is a whole host of evidence which shows that Watt steam engines were shipped to slave owners in the Caribbean for use on sugar plantations as they allowed greater extraction of juice from sugar canes (Mullen, 2020).

A Change of Heart?

Despite the overwhelming evidence which links Watt to the trade of enslaved people, there is also evidence that he advocated for the abolition of plantation slavery. In 1790, enslaved people in Haiti revolted after the failure of a campaign which fought for black voting rights. The Haitian revolution soon followed, Haiti became an independent nation, and was the first country to abolish slavery. Correspondence from Watt and Boulton to slave traders in Haiti at the time shows that Watt halted production on a steam engine commissioned for the slave traders. In this letter Watt also states, “We sincerely condole with the unhappy sufferers, though we heartily pray that the system of slavery so disgraceful to humanity were abolished by prudent though progressive measures” (Watt, 1791). It is important to keep in mind that 6 months prior to this letter, William Wilberforce introduced the first motion to parliament for the abolition of the trade of enslaved people (Mullen, 2020). Whilst we can only speculate, it is possible that Watt was conscious of a changing social attitude towards slavery, and wished to erase his past links to slavery by being seen to advocate its abolition.

The connections between James Watt and the trade of enslaved people have only recently been acknowledged. Institutions like the University of Glasgow have published reports which recognise that some of the gifts they received from James Watt and other 18th century alumni were the result of profits from the trade of enslaved people (Mullen and Newman, 2018).

Acknowledging that James Watt had connections with the transatlantic slave trade is not to diminish his achievements. The invention and development of his steam engines changed the world, and powered the industrial revolution. It is important, however, to acknowledge the role he, his family, colleagues, and his inventions had in such a terrible part of the world’s history, and to ensure that he is not blindly celebrated in today’s society.

By Steffany Norma McGeachin, Great Place Volunteer November 2020.