As Scotland’s Garden and Landscape Heritage (SGLH) Chairman I am very proud to present this story about Balquhatstone Estate by Diana Hardstaff, volunteer on the Glorious Gardens team assigned by SGLH to the recording of non-inventory designed landscapes and gardens in the Falkirk area. The Glorious Gardens project was launched in Falkirk in 2015 and was funded by Historic Environment Scotland. This is one of the 16 sites covered by SGLH in this area. A similar project was carried out in the Clyde and Avon Valley, and we are currently planning a third phase, which will focus on sites in East Lothian. For more details, please go to https://www.sglh.org.

The Gardeners of Slamannan

Slamannan can be a bleak wind-swept place in winter. According to one story the name Slamannan is derived from the words of a servant who was sent by the Earl of Callendar to plough the moorland and on his return stated that the land ‘would slay both man and slave.’ It doesn’t take much to imagine the drudgery of the local Victorian coal miners.

So, it’s quite surprising to learn that one hundred and fifty years ago the gardeners and miners of Slamannan were growing and exhibiting all manner of plants – exotic palms and fuchsia from hot houses, and geraniums, carnations, marigolds, parsnips, carrots and leeks from their gardens.

By Royal Charter

The story starts around 1513, long before coal was king. At the time James Waddell and his wife Jane Russell were in the court of King James IV of Scotland. The Register of the Great Seal of King James V records the first charter to the Waddells of Balquhatstone in November 1536. They built themselves a country house in the area now known as Slamannan and the family stayed put for the next five hundred years.

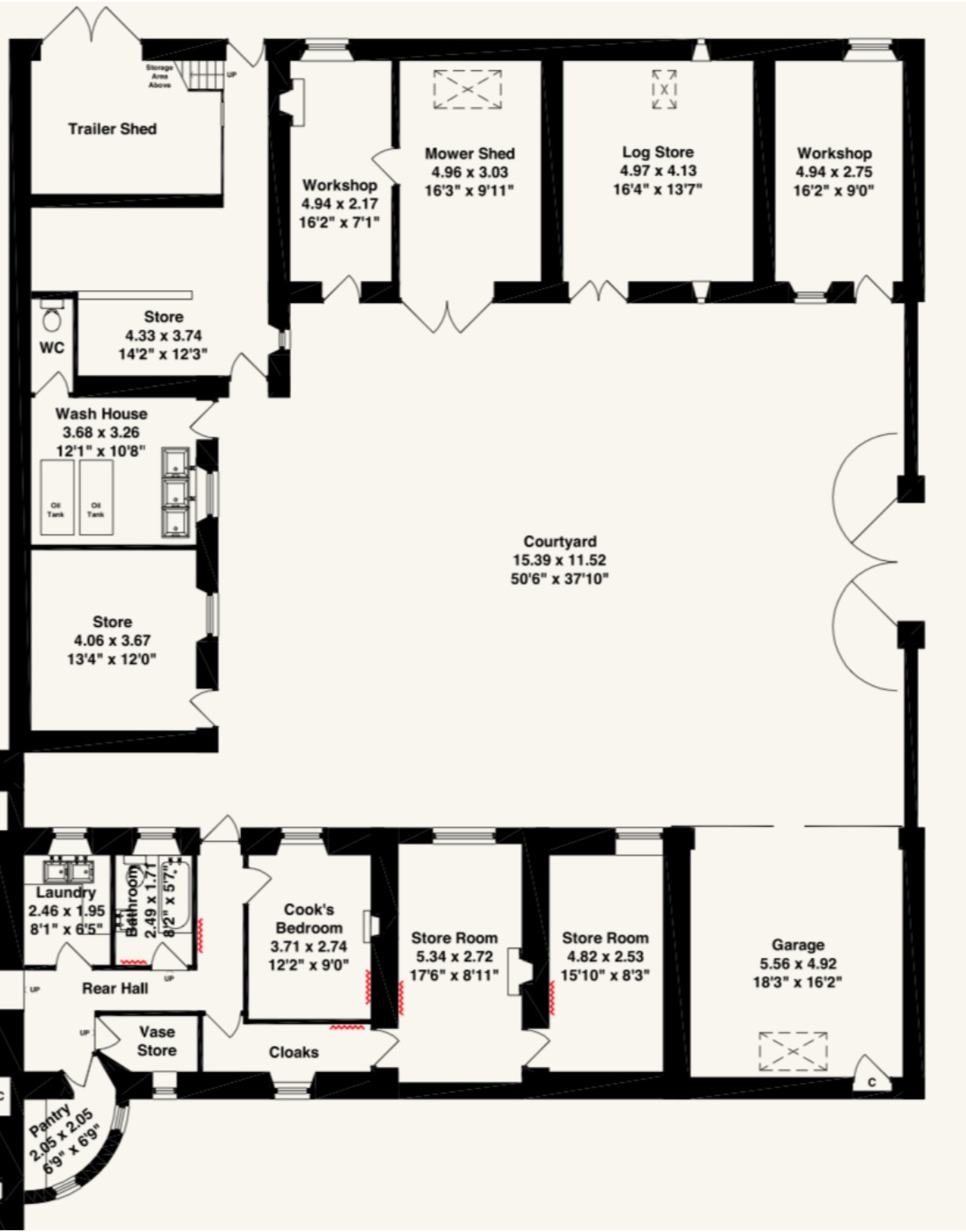

By the early part of the eighteenth century Binniegreen, a small cottar house, had been built in the grounds. The area was almost certainly a drying green where clothes and linens (probably produced locally) were laid out. That the Waddells employed staff to run their estate is evident from reference to the “wash house,” “laundry” and “cook’s bedroom” shown on the modern layout plan of the U-shaped steading next to their house.

Coal Pits, Hovels and Horticulture

Coal mining grew phenomenally quickly around Slamannan in the middle of the nineteenth century. The collier’s grim life is recorded in the Mining District reports of 1859, which state that “the effect of crowding people together in long rows of hovels is to encourage and perpetuate dirt and discomfort… the furniture out of order and neglected, the floor black with dirt, the bedclothes nearly of the same colour… when he comes home from his day’s labour, as black from head to foot as the coal he has been working, … [the collier] washes his face, neck and breast, his arms and his shoulders and his legs up to his knees – often not so far; he washes his head on Saturdays. The whole of the rest of his person remains untouched by water… I found the back of every one of them were quite black, and every one gave the same reason in the same words for not washing his back, namely “that it would weaken it.””

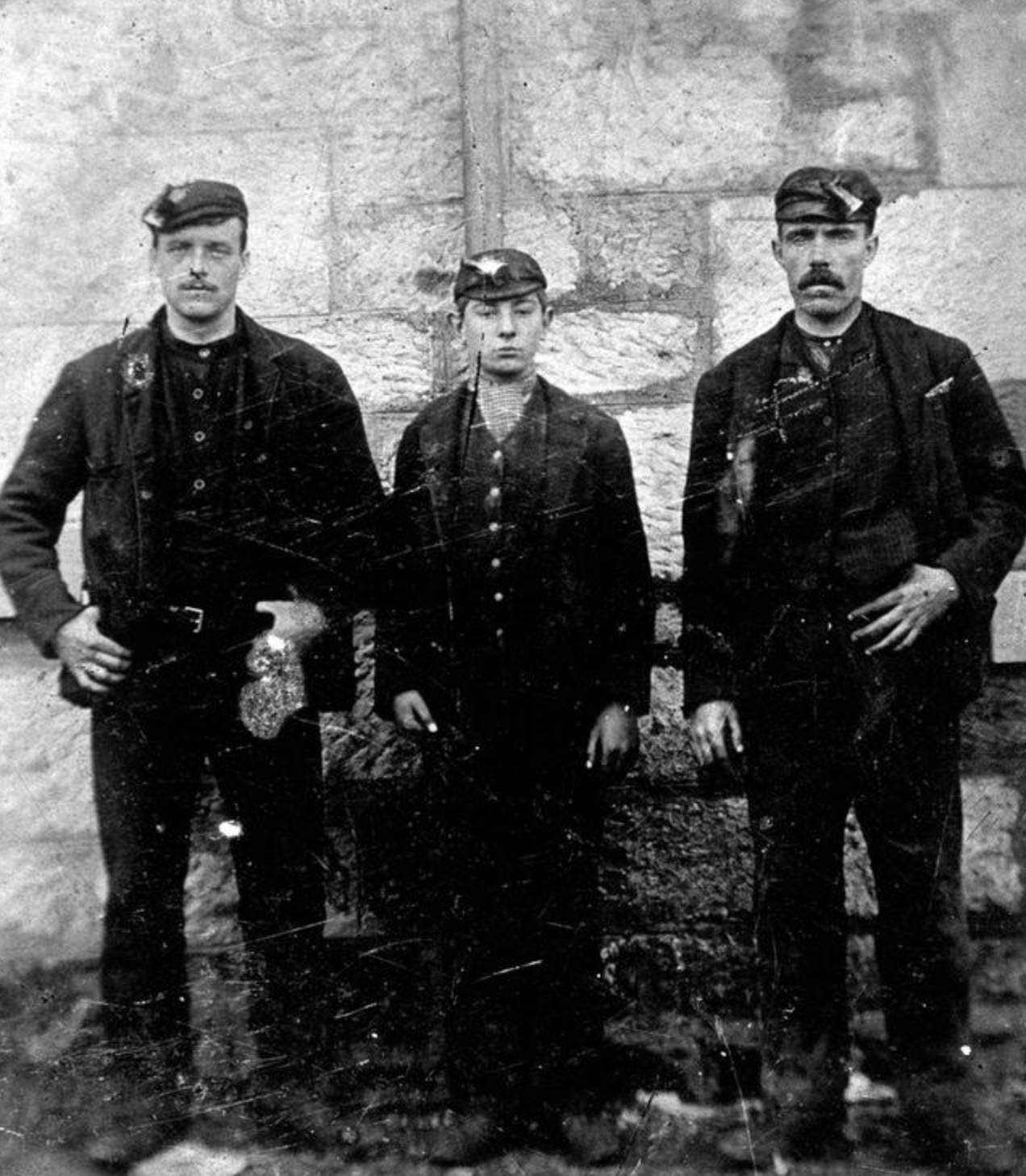

There was pressure on industrialists to do something to improve the living conditions and lives of the workforce. Nathaniel Paterson (2nd right standing below), Glasgow clergyman and one of the “Disruptors” of the Church of Scotland monopoly, wrote in The Manse Garden (1836), that he encouraged his parishioners to grow vegetables and to “ornament” their cottages with roses, ivy and fruit trees, because “when home is rendered more attractive the market gill [tavern] will be forsaken for charms more enduring.” Gardening expert Shirley Hibberd wrote in 1877 that “Contact with the brown earth cures all diseases.” Gardening kept men away from militancy, out of the pubs, and brought them closer to God.

Not surprisingly, during the mid to late nineteenth century, many Horticultural Societies and Floral Societies were set up in pit villages and industrial towns. At least seven societies were established in the Falkirk area. In 1859 the Slamannan Horticultural Society held its first show in the parish school. It was held every year thereafter until 1909.

The Glasgow Herald’s “own correspondent” reported in 1875 that the “experience of a few years has shown that with a very little trouble at first and a small amount of judicious encouragement the taste [for gardening] has been very successfully introduced among [colliers] … they offered prizes for the best kept display of flowers and vegetables… a great amount of emulation had been called forth by the prizes offered by the Horticultural Societies.”

Skull and Cross Bones

Life wasn’t a bed of roses in Slamannan though. In 1878 the miners of the town began a five-week strike for better conditions. It ended in widescale evictions which sparked a violent riot in the town. The Falkirk Herald in April 1878 reported that a “mob” demolished the office of the works at Balquhatstone colliery and smashed up an adjoining signal box. They threw stones “big as turnips” at one coal master’s windows and “tore books from their bindings and threw portions of furniture out of the windows. Shrubs on the lawn were wantonly uprooted and greenhouses destroyed.” The coalmaster “hid in a press and eventually had to run a long distance for his life.” Prior to the riot he “had received threatening letters with cross bones upon them and one represented his house with the word “Dynamite” written below.”

From the Garden of Eden to Gethsemane

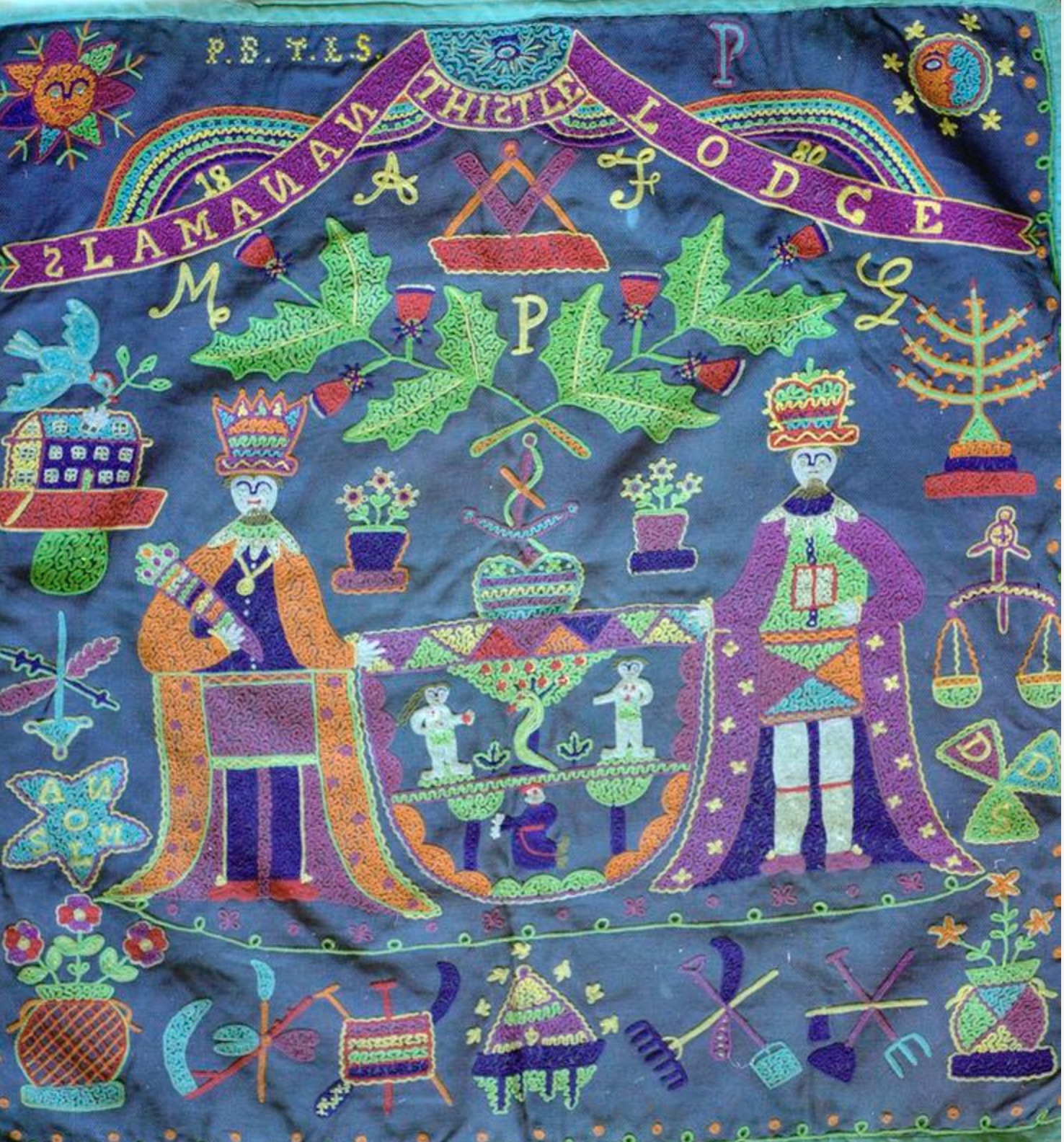

Things seemed to be looking up for the miners when in 1880 the Slamannan Free Gardeners Friendly Society was founded. Originally a trade-based organisation, similar to the free-masons, by the late nineteenth century free gardener societies had evolved into organisations whose main focus was to provide financial assistance for subscription members such as funeral costs and pensions.

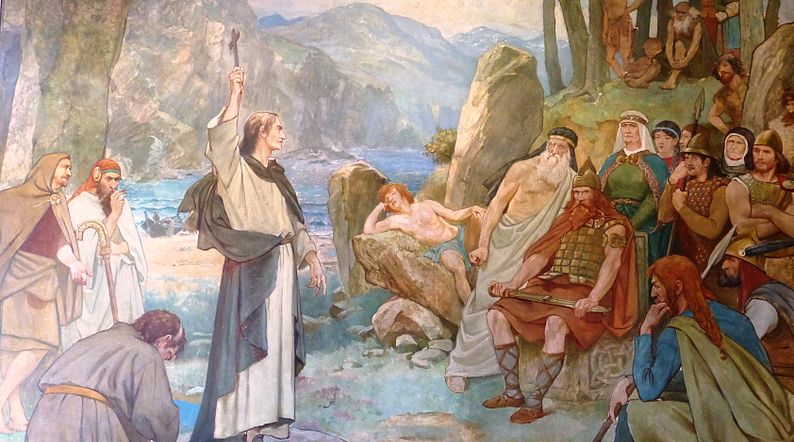

Nevertheless the Slamannan Free Gardeners’ banner still displayed all the biblical iconography of the gardener– Adam in the garden of Eden (representing 1st degree apprentices), Noah and the Ark (representing 2nd stage journeymen travelling to Gethsemane) and Solomon with olive trees (the third or master gardener able to grow olives, and sometimes even grapes, in Scotland). The banner also depicts a compass, set square and a knife representing respectively, direction, square moral beliefs and the pruning of vices along with other gardening motifs.

Competition Gardening

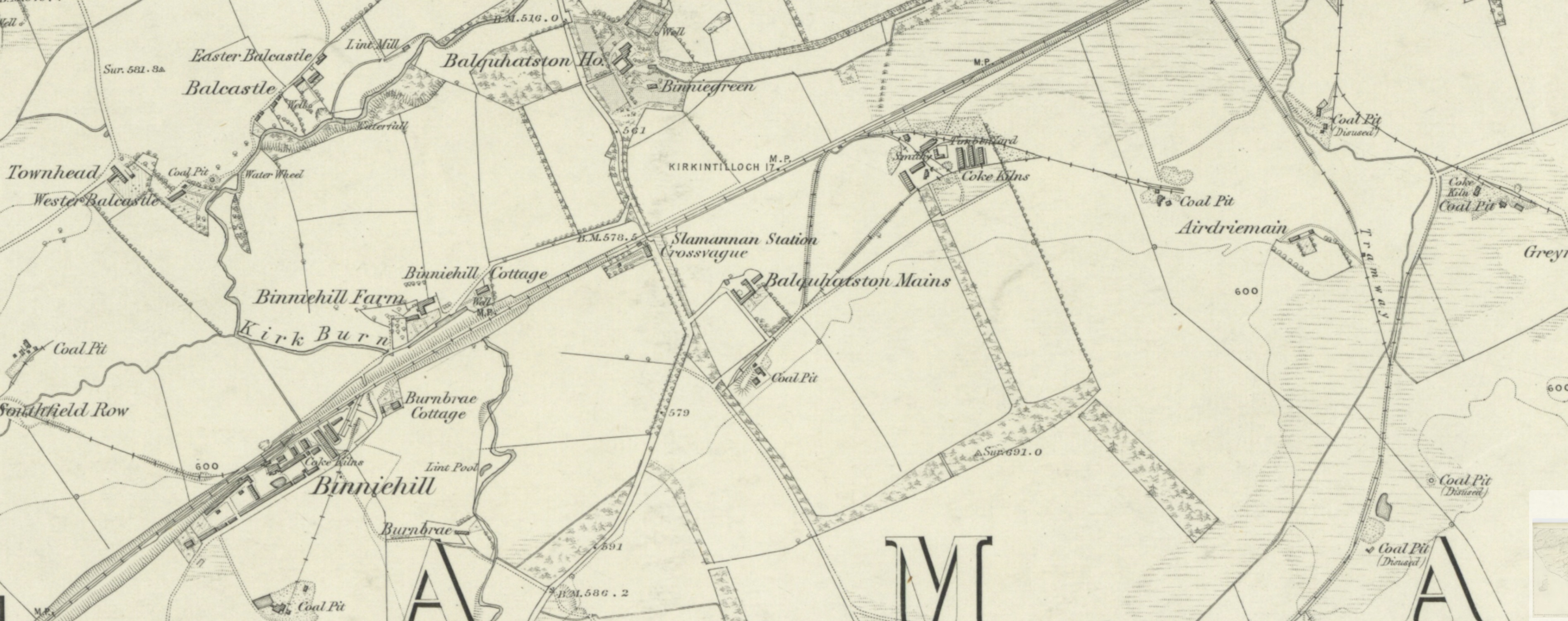

Near the pits and hovels Victorian life at Balquhatstone was very privileged. Plants for the table and the house were grown in an unusually diamond shaped walled garden within the grounds. We know from nineteenth century maps that the walled garden was divided into four quarters by paths with a greenhouse against the east facing wall by 1899. A modern layout plan has annotations for a tomato house, a plant house and a vine house – perhaps indicating Victorian uses. There was also a “potting shed” and “boiler house.”

The Peddie Waddells regularly exhibited plants at the annual Slamannan Horticultural show. On the 12th September 1896 the Falkirk Herald reported that there were 129 classes. These included: Greenhouse, Frame or window; Amateur greenhouse; Pot plants; fuchsia, rose, pelegonium, geranium, carnations, pansies, asters, marigolds, parsnips, carrots, leeks, German greens, parsley, rhubarb and cabbage. The “tables were erected the previous night and in the early morning the competitors were astir, and by 10am everything was ready for the judging.” According to the report “Mr. James Chalmers [of Balquhatstone] was as usual to the front and deservedly won a splendid prize for pot plants – a collection to cover a space of 8ft by 6 ft.” The newspaper reported in 1900 and 1902 on the “usual large collection of decorative plants including palms and fuchsia etc. kindly lent by Mr. Peddie Waddell of Balquhatstone and which went a long way to increase the attractions of the exhibitions.”

Floral Arch

Events at Balquhatstone were also the focus of local excitement. In September 1902 the Falkirk Herald reported that “Slamannan was agog with festive excitement on Thursday last…The wedding [of Margaret Peddie Waddell to her cousin] was fixed for 2 o’clock at Balquhatstone. By half past one a railway saloon brought a bevy of guests from Edinburgh. The house was lavishly decorated with beautiful plants and cut flowers from Balquhatstone gardens and greenhouses and the entrance gateway was surmounted by an arch of heather and laurel with flags either side… [the bridesmaids] carried bouquets of pink carnations.” Church fetes were also held in the estate grounds.

The End of a Way of Life

In the early years of the twentieth century coal production fell steeply, and the pits closed as quickly as they had opened. As the number of miners fell, membership of the Horticultural Society and the Free Gardeners Friendly Society dwindled. Descendents of the Peddie Waddells remained at Balquhatstone until the death of the last family occupant around 2010. With no-one in the family willing or able to take on the house it was sold, ending the story of the Waddell’s family seat – part of some of the most tumultuous years of Slamannan’s history.

By Diana Hardstaff, Scotland’s Garden and Landscape Heritage volunteer.