Find out about Falkirk’s forgotten botanist and learn how to identify some of the extraordinary plants he collected.

Introducing Forrest

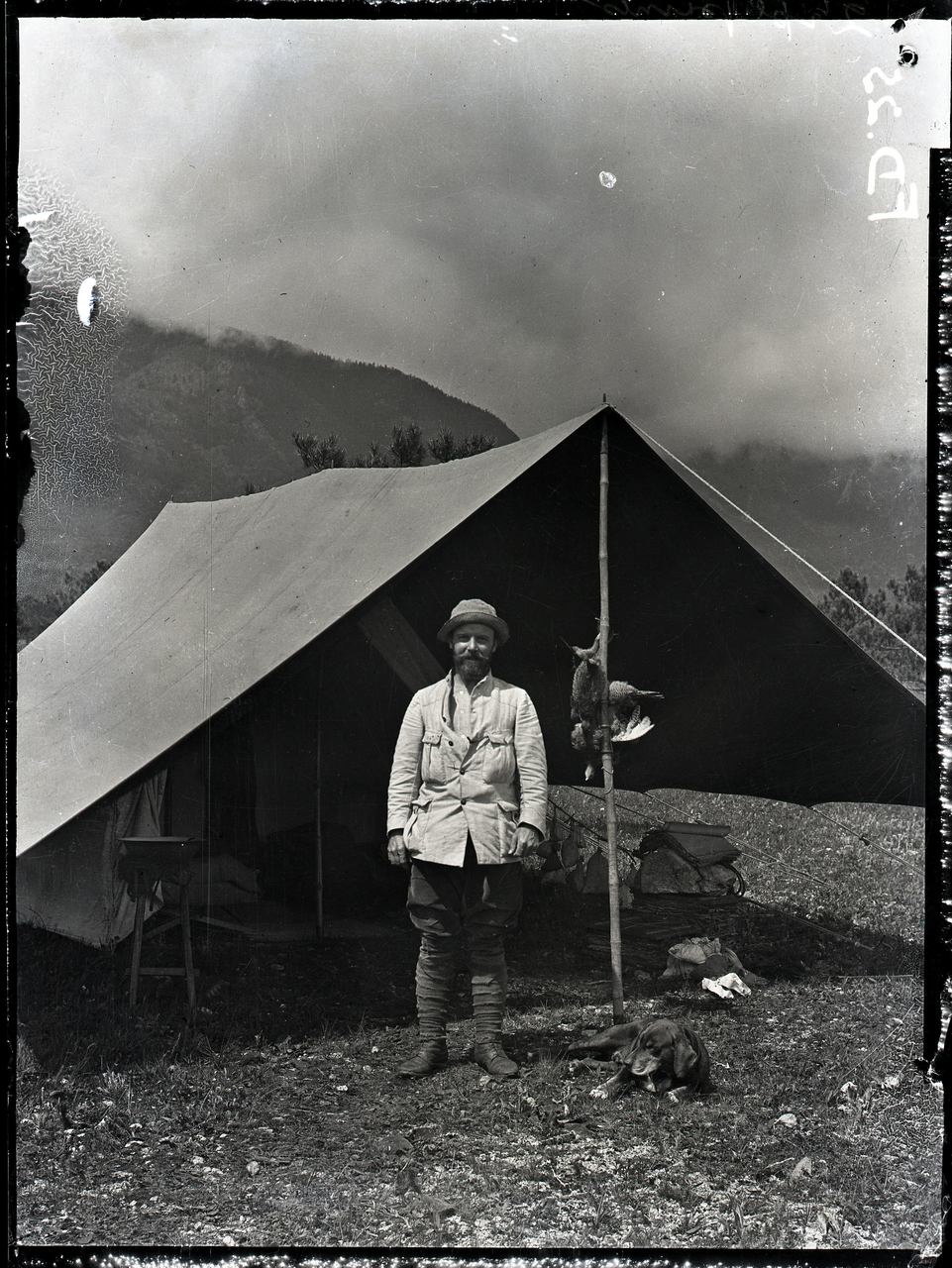

Successful botanist and “Falkirk Bairn” George Forrest was born in 1873 and died in 1932 (Paterson). It is recorded that many members of his family were from Larbert and Stenhousemuir, with some being employed by The Carron Company (Watters).

Forrest went to school in Kilmarnock, and as a young adult worked in a chemists (Scott). Ian Scott, writing in the Falkirk Herald (April 2020) noted that he “inherited some money and set off to farm sheep in Australia and dig gold in South Africa.” In 1902, Scott adds, a “chance meeting” gave him the opportunity to work in the herbarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh – a role that later allowed him to discover plants all over the world.

It is believed that Forrest discovered 1,200 species of plant that were “new to science” (Plant Explorers). The majority of Forrest’s plant hunting adventures were to Burma, Tibet and China, and he brought back ‘vast quantities of seed, hundreds of live plants and thousands of specimens (Australian Garden History).

The main records of Forrest’s life and work can still be found at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh. They have a large collection of archival documents related to Forrest. Unfortunately, because of restrictions on travel and the closure of libraries and special collections due to Covid-19, I have not been able to access archives and collections to inform this article. My instinct when first beginning research on a figure like Forrest would be to look for records, images and archive documents and try to tease out a story, but in this case I had to think differently.

Memorialising Forest

When I first started writing this short article I hoped an alternative angle would be to search out and document tangible traces of Forrest’s life in Falkirk. A search, and outreach efforts to the local community via social media have thus far not found any memorial, plaque or garden in the Falkirk area that remembers Forrest’s contribution to botany.

Discussions documented in local newspapers over the last 40 or 50 years note interest in creating a memorial to Forrest, but this has not materialised. A note in the Falkirk Herald (August 1945) records that “It is proposed to lay out a plot containing specimens of the plants and shrubs introduced into this country by him, and to erect a commemoration plate or tablet (“Proposed Memorial”). Currently there are also no gardens, specimens or propagules in Falkirk that can be firmly linked to Forrest or his work (Scott). The Chairman of the Friends of Dollar Park group, Les Pryde, was a principal parks officer for Falkirk Council in the 1980s (Scott). In a discussion in April 2020 for an article in the Falkirk Herald, Pryde explained that a “George Forrest Trail” was “created on the south side of the park with several half-circle beds planted out with examples of Forrest’s flowers” (Scott). Local historian Geoff Bailey has researched Forrest previously, and noted that in the 1970s a number of plants connected with Forrest were put into the arboretum in Callendar Park (Personal Correspondence).

Beyond Falkirk

Looking beyond Falkirk, there are a few memorials to Forrest. Maxwell Park in Glasgow has a small memorial bed and information board, and presents examples of specimens introduced to the United Kingdom by Forrest. Benmore botanic gardens in Dunoon has a large living collection of plants many of which connect with Forrest. As noted above, the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh has an extensive collection of Forrest’s materials, including notes, records and photographs, held at the RBGE archive.

It became clear to me that the legacy of Forrest’s plant hunting adventures can most clearly be seen in the colour and variety of plants many of us have in our gardens, or that are planted in parks around Scotland. They may not be sign posted, but it is likely that species introduced by Forrest could be identified by most of us in places close to home.

Flora

Some of the plants Forrest introduced included “numerous buddleias, anemones, asters, deutzias, conifers, berberis, alliums and cotoneasters” (Plant Explorers). It appears Forrest was particularly fond of certain plant types, as he introduced a large number of Rhododendrons and over 50 species of Primula.

In the hope of seeing some of these plants for myself and describing some of the identifying features to look out for, I visited the Botanic Garden in Edinburgh. I do not know a lot about plants, the conventions that guide their naming, and I lack a grasp of the language used to describe their features, but I thought this was a great opportunity to learn more. I hope to point out some specimens that a novice might be able to find.

Acer davidii “George Forrest”

The Acer davidii “George Forrest” was first on my list as I had seen an example of it illustrated in a text from 1952 (Cowan 1952 p.96). An article on the Botanic Stories website helped me to locate the tree, with author Alan Elliott noting that the tree was “growing near the southern boundary of the garden, to the west of the woodland garden.”

The specimen was certainly impressive, and its beautifully pale green ovate leaves were on show when I visited in late July 2020. The tree is often described as having “snake-skin bark” (Cowan p.97). The amazing, gnarled texture that can be seen and felt on the trunk made clear why it is described like this. The tree is also described as having “glabrous leaves [that] have finely serrated margins” (Cowan p.97). You should be able to see some of these details in my photographs.

Forrest carefully numbered and logged each of the specimens he gathered and noted where they were found. In nature this would typically be found of the eastern side of what was recorded in 1952 as Li-chiang Range (Cowan p.97). It is possible that this meant the area to the East where the Hengduan mountains encircle the city.

Pyrus pashia

The next plant that I wanted to see was a Pyrus pashia, a wild Himalayan pear which had its 100th birthday on July 18th 2018. In his notes George Forrest simply described the plant as “a shrub of 10-30ft growing in open thickets” (Hinchliffe). Indeed, at first sight the Pyrus pashia growing in Edinburgh looks to a non-botanist like a simple bush. When I looked closely at the plant I could see small speckled green pears sprouting from the limbs. The leaves were beautifully glossy and had lovely rippled edges. I believe that before the fruits grow the tree has small white blossoms.

Other Plants

I was pleased to find these two specimens at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh but was unsure how to go about finding more specimens connected to Forrest. In September 2020 I visited the Cluny House Gardens in Aberfeldy, on a trip unrelated to Forrest. The Cluny House Gardens website notes that the garden contains a number of species connected with Forrest, although on my visit I could not identify any. A visit in Spring may be more fruitful for Forrest plant spotters, with multiple species of primula including Primula aurantiaca; Primula bulleyana; Primula chungensis; Primula flaccida; Primula forrestii; Primula sonchifolia; Primula vialii flowering at this time (“The Plant Collectors”).

One of these species, Primula bulleyana, is named in honour of Arthur Kilpin Bulley, a patron of Forrest (Leapman). The plant, commonly known as Bulley’s primrose, has long thin stems and bright orange bell shaped flowers. A number of specimens are also named after Forrest: Rhododendron forrestii, Pieris Formosa var.forrestii and Clematis forrestii are just a few of them (Australian Garden History, p.12).

The final plant connected to Forrest that I have been able to identify in the local area (there are probably many more) is hypericum forrestii. This semi-evergreen shrub has butter yellow flowers in Summer and Autumn. It has short matte green ovate leaves. The Royal Horticultural Society describes the plant as having “usually paired leaves and showy yellow flowers with prominent stamens, followed by capsules, occasionally berry-like.”

Unnamed Collectors

I am not an expert on the politics of plant collecting, or on Forrest, but it appears that Forrest gained a lot from his expeditions without giving much back to the local people who he employed. Indeed, it seems that Forrest looked down on local people in the areas he worked in, writing that “...the collector has to seek his specimens among savage or semi-civilised peoples, who, in most instances, strongly resent his intrusion into their midst; thus seldom a year passes without toll being exacted in one way or another” (Forrest p.325). What is clear in the extant records is the sheer scale of Forrest’s plant collecting operation, and his need for the help of local people. Not all of them welcomed him, and Forrest fled an indigenous "Lama sect" who attacked his entourage, which was evidently extensive (Paterson). He recalled that “Of my own 17 collectors and servants only one escaped” (Forrest).

George Forrest is recorded as being the first Westerner to discover these plants, but a record of the contributions of those in Burma, Tibet and China that worked with him to find, gather and record specimens are missing from much contemporary writing, as well as from the records made by Forrest himself. In the few sources where local people’s contributions are mentioned, they are regularly not recorded by name (Pateerson is a notable exception and includes images and some identifying details of a small number of those working for Forrest). I hope that further archival research may allow future researchers to expand on this area.

So, to return to Forrest’s legacy in Falkirk. In 1932, W. Wright Smith wrote that “Forrest’s contribution to the genus is as his memorial,” something “more lasting than bronze.” (Cowan p.4). Whilst this statement was specific to Rhododendrons, it succinctly explains what I have shown. A formal memorial to Forrest does not exist. For the amateur plant hunter, limited by travel restrictions and knowledge of horticulture, this handful of plants are the most tangible connection to George Forrest that can be found. I encourage you to search out a little bit of Forrest’s legacy yourself.

By Rowan Berry, Heritage, engagement and interpretation intern at Falkirk Community Trust 2020, Hidden Heritage: Industry and Empire project.

With thanks to Arnotdale House, the Cyrenians, Friends of Dollar park, Falkirk Rotary Club, Les Pryde, Geoff Bailey, staff at the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh and all of the community contributors on social media.