The “Day in the Life of …” is a project that aims to share the stories of local people who worked in the industry. Life in the industry might not be exactly what you think; the stories we listened to were full of comradery, passion and pride. Follow our placement student Katerina Vilemova as she interviews two members of the Greenhill Historical Society, and discovers what a day in the life of a foundry worker would be like.

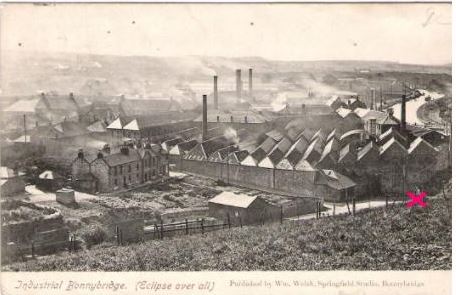

About Bonnybridge

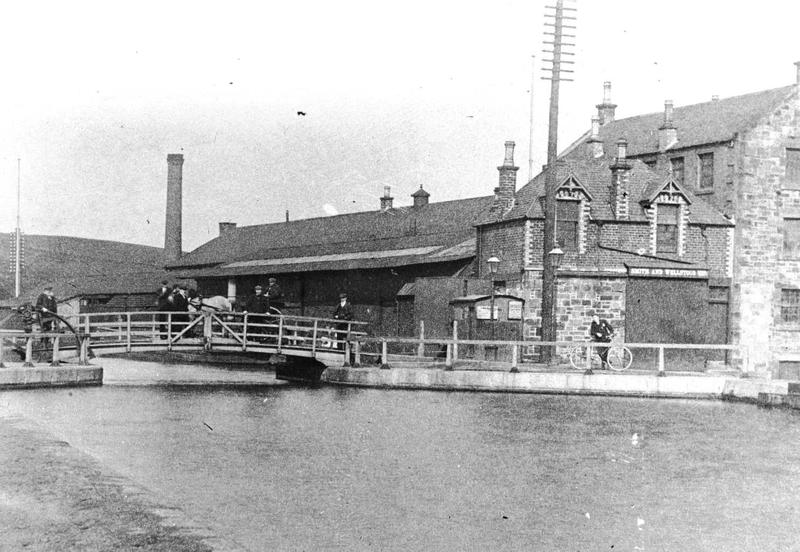

Bonnybridge is a small town located on the Northern side of the Falkirk District. The area is mentioned as early as 1648, under the name “Fuird of Bonny”, and was a part of a village known as Bonnywater. The name closer to the one we know was first mentioned in 1682, when the Bonnybridge area was known as “Bonniebridge”. In 1878, Bonnybridge became an independent parish. During that time, industries (such as brickworks, chemical works and munition works) were the backbone of the local community. Bonnybridge is especially famous for its iron foundries, such as Smith and Wellstood Foundry (The Columbian StoneWorks), which made metal heating stoves, one of which was sold to Florence Nightingale, who even wrote a letter to express her gratitude! The letter is stored in the Greenhill History Society’s rich archive.

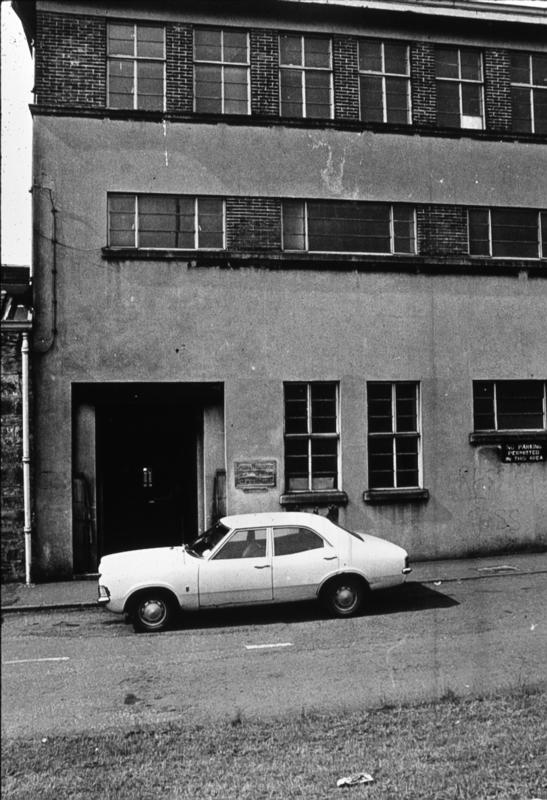

The iron foundries in Bonnybridge were: Messrs. David Gillies & Sons, Rollo Industries (still operating beyond High Bonnybridge.), Messrs. E. Dyer (Engineering) Ltd., Smith, Wellstood and Ure & Co., Campbell Ferguson & Co., later became, George Mitchell & Sons Ltd., Woodlea Foundry, Broomside Foundry Co. (1922) Ltd (Also known as The Puzzle for its apparently rather haphazard layout.), Messrs. Lane & Girvan, Chattan Stove Works (Bonnyside Road), Messrs. E. & R. Moffat, Dempster, Moore &Co. (Machinery) Ltd., Glasgowm, Banknock Foundry, Broomridge Foundry.

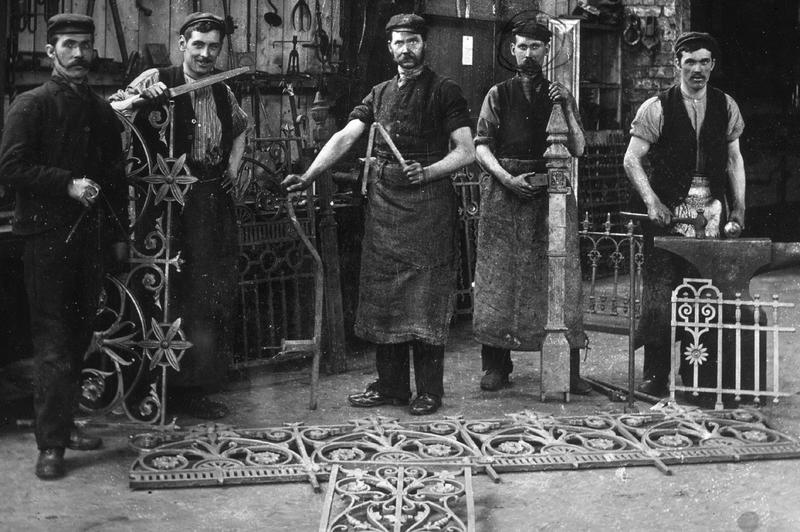

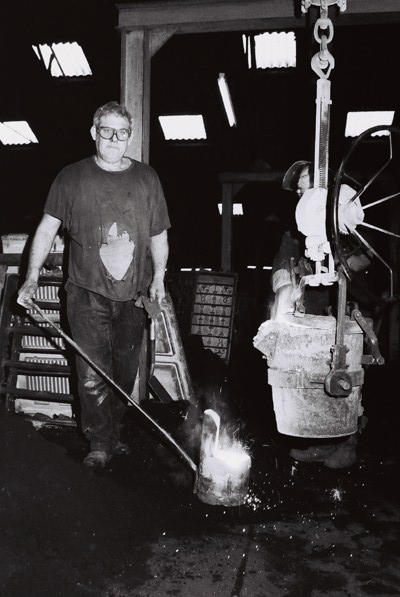

The Forth & Clyde Canal helped Bonnybridge become a centre of industrial production. The proximity to the canal made it possible to import large amounts of “pig iron” (slabs of iron) and coal that were needed for the production of iron goods. Bonnybridge ironworks mostly focused on the process of moulding and casting. So what was it like to work in the foundry? You can find the answer by listening to the stories told of the people who got to work in the scorching foundry heat to create beautiful objects such as the beautiful lustre beetle boot puller!

The story of Alex and Margaret, Bonnybridge locals who worked in the local industries

Alex

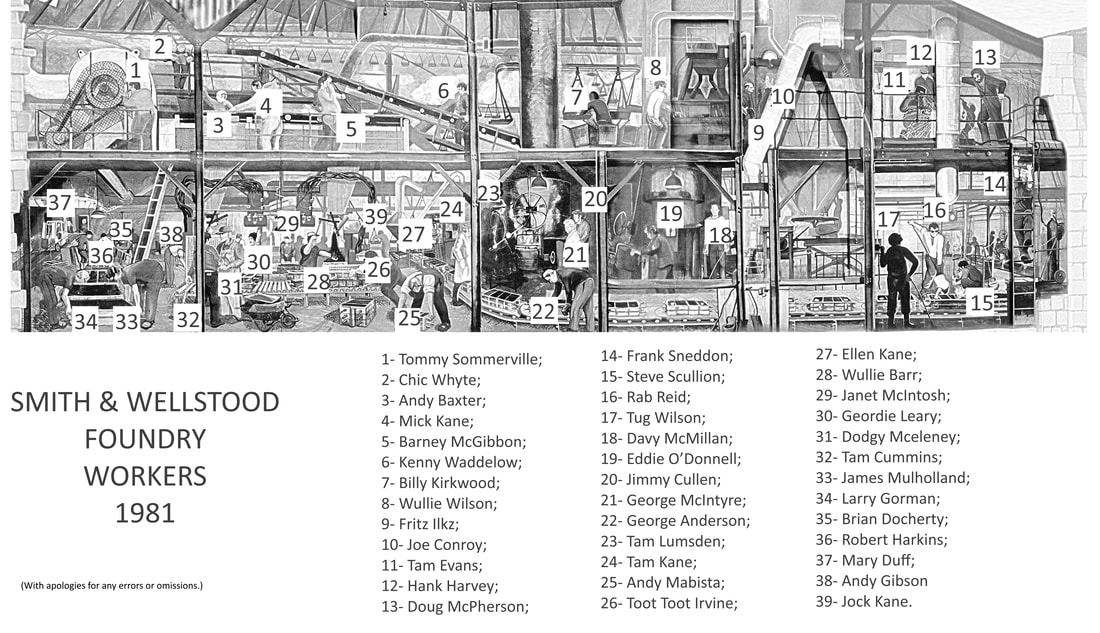

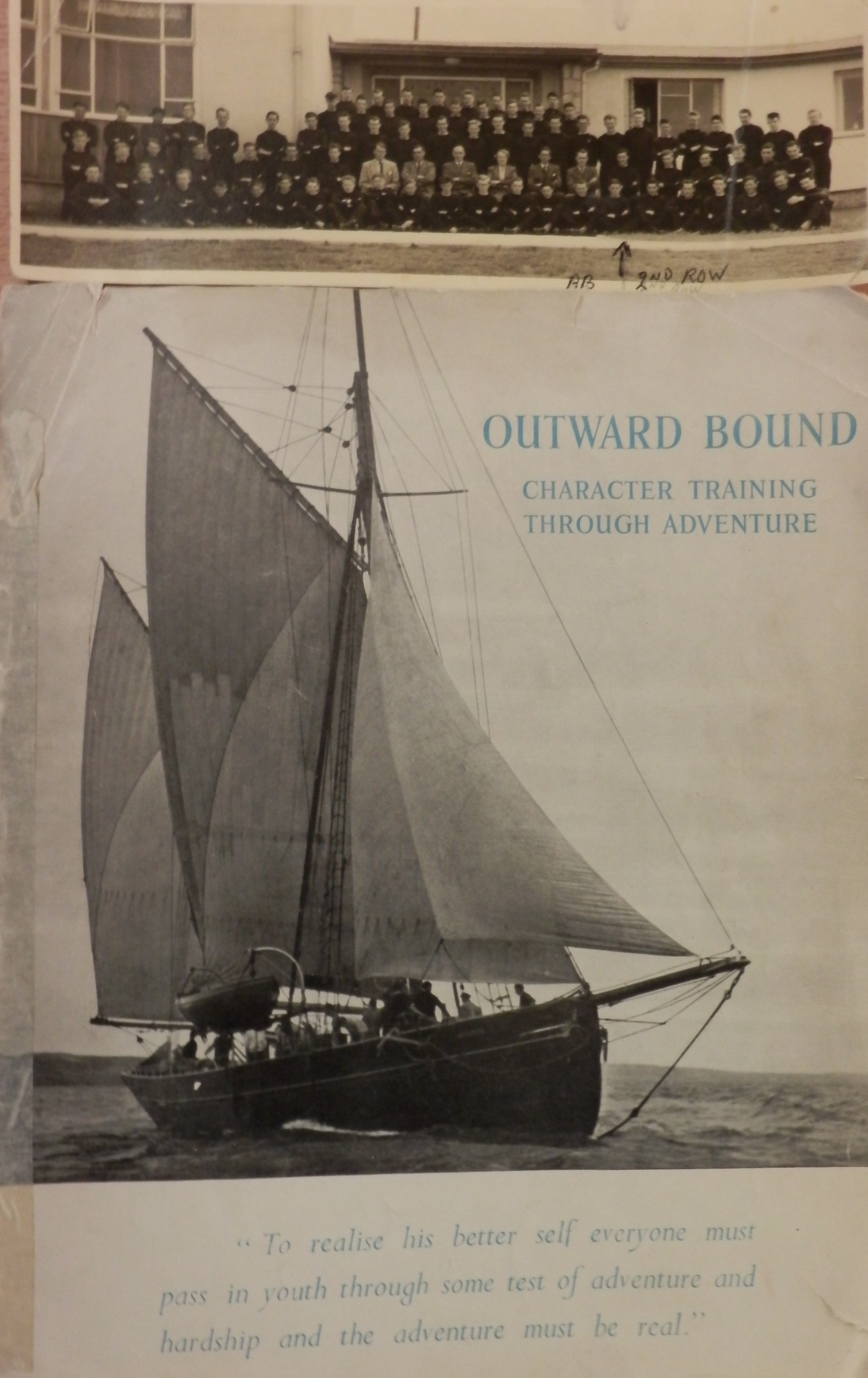

Alex was born and raised in Bonnybridge. Alex’s career began when he was 15 years old, in the 1950s, as an apprentice in the Smith & Wellstood foundry, pursuing a career as a sheet metal coppersmith. He worked in various departments of the company, gaining exciting experience, and developing a passion for learning the trade.

Margaret

Margaret worked as an enameller at the Chatton Foundry and the Smith & WellStood foundry. She tells us that her job was quite hard but very rewarding. Margaret notes that, despite the fact that she had the same job in each foundry, the work was all very different.

What it was like to be a worker in the industries back in the day?

As we sit in the Bonnybridge community centre, I ask Alex and Margaret about their life in the industry. Working in the foundry was not an easy job, but being part of a team, definitely made the experience more palatable. As the two explain, socialisation and comradery was an important part of their work life. Due to the ironworks being such an important part of the local economy and politics, the companies tried to take good care of their employees. By the end of the Second World war, most foundries in Falkirk established Welfare Committees which focused on providing the employees with leisure activities. For example, Denny Ironworks in 1950 dedicated a full wing to the purpose of socialisation, which included a common room, an ambulance room, a canteen and a bathhouse.

Margaret talks about her experience as a woman in the industry

General working conditions in the foundries were quite dangerous, and accidents were commonplace. People being trapped in the moving elements of the machines, fire, splashes of molten metal, heat, dust and gasses… there were a lot of ways to get hurt. A big step forward in the safety procedures was the implementation of Public Health (Scotland) Acts 1897-1945. However, working in the industries was even more challenging for women workers. After the second world war, Britain enjoyed a period of sustained economic progress. For that reason, the government encouraged women to get a job. What might have seemed like a win for women rights was however a more complicated affair. Despite the fact that the percentage of women in the workforce was growing, what was considered as “women’s work” often included routine, repetitive and lower-wage jobs, such as cleaners, midwifes, nurses or clerical staff.

Women were considered “secondary workers”, and their wage was reflective of that. Moreover, women enjoyed much less job stability than men. In the early 1950s, many companies and employers still worked until the “marriage bar”. Marriage bar was a measure introduced in the inter-war era in order to ensure that men remain the breadwinners in a family, and also to ensure women will stick to their duty of care.

Essentially, it discriminated against married women and disabled women to have both a family and a career. While the marriage bar was lifted in most workspaces by 1944, some places followed it until it was made illegal under the Sex Discrimination Act 1975. Margaret shared her experience with us. She told us that although her work was of high quality and done with confidence, she was often paid less than her male co-workers for the same work. This, however, did not discourage Margaret!

In the interview, I asked Margaret and Alex about their time in the industry. The picture they painted in their stories is a very different compared to the state of contemporary industries in Scotland.

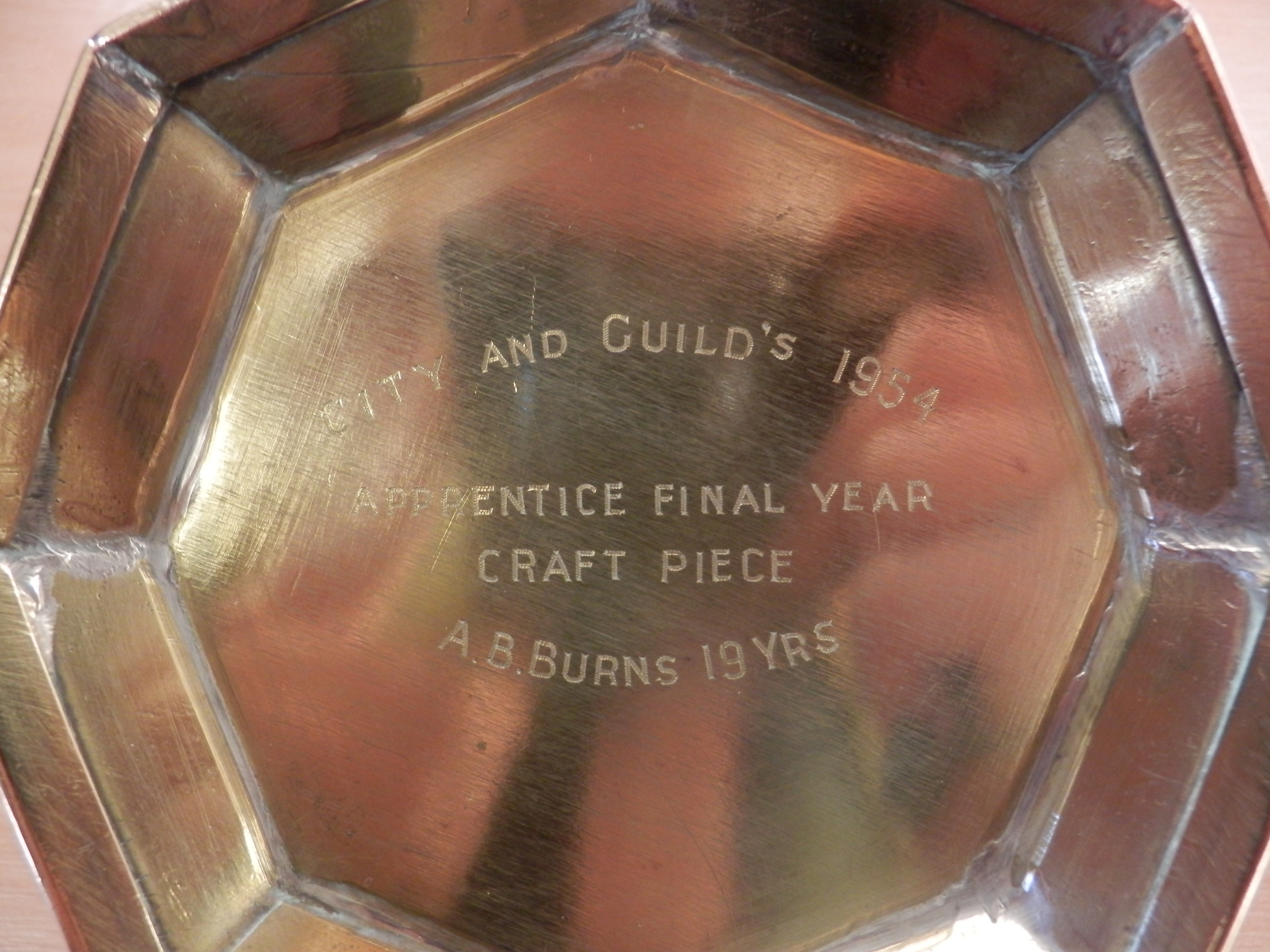

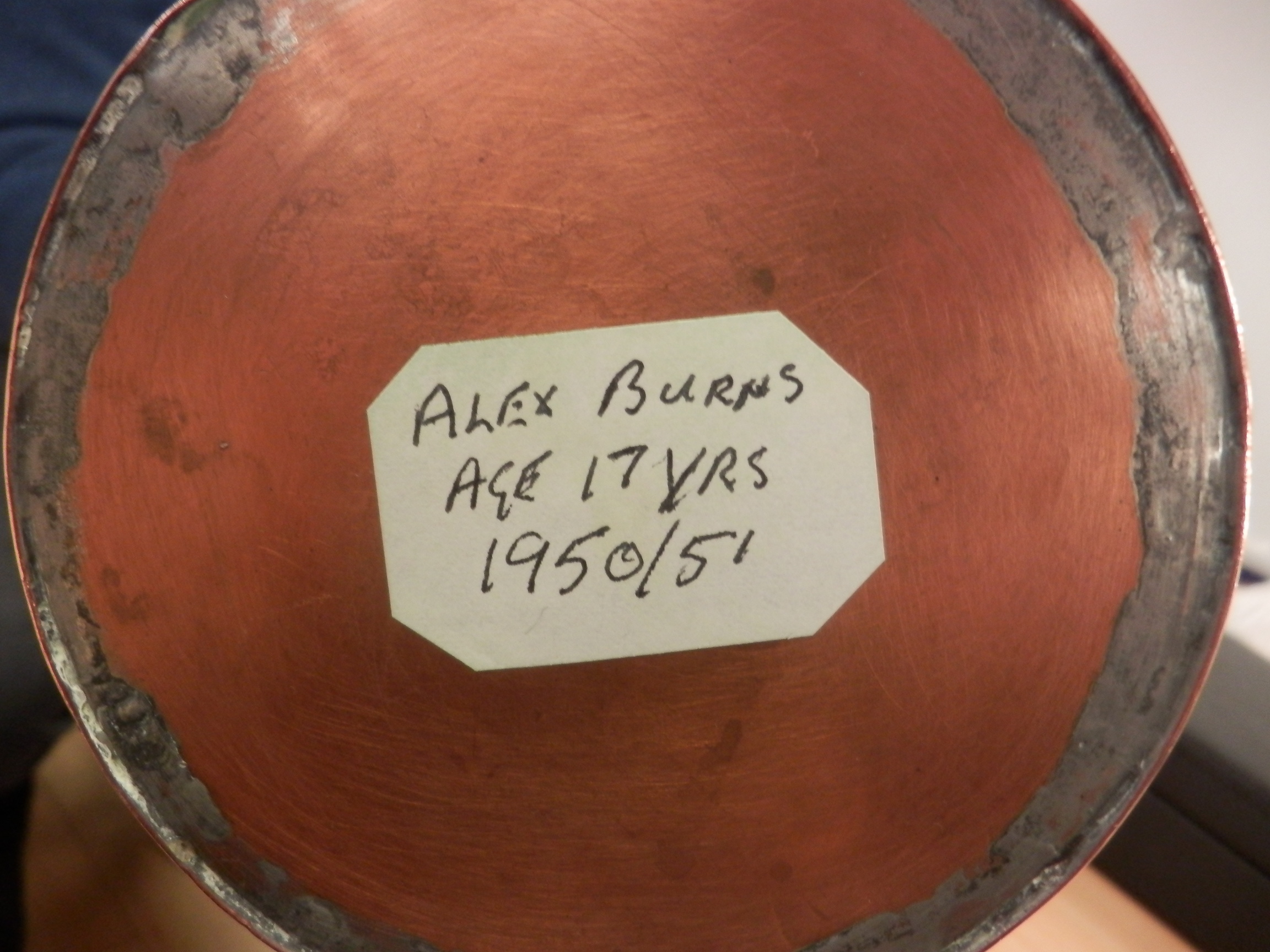

Showcase of some of the objects Margaret and Alex made

The Greenhill Historical Society archive holds many precious objects, such as the beetle boot pullers Margaret enamelled. Other objects in the photographs below were made by Alex while he was an apprentice sheet metal coppersmith.

Epilogue

The project was definitely an adventure! As I am not native to Falkirk, I enjoyed getting to know the place and especially its people and their stories. My research led me through several archive collections and hundreds of photographs, artefacts, and maps. However, there was something special about listening to the stories in person, getting to know the people who experienced them. I hope this project helps to remember and share their stories.

I would like to thank all the lovely people from the Green Hill Historical society for their help, patience and for sharing their stories, especially Alex, Margaret, Paul and Phil. Anybody interested in what they are up to should visit their webpage which was a great help and source for my research (https://greenhillhistoricalsociety.weebly.com/) and read their local publication Bonnyseen Magazine (https://greenhillhistoricalsociety.weebly.com/bonnyseen.html).

Katerina Vilemova is a student of MRes in Social Anthropology at the University of Aberdeen. The project ‘A Day in the life of’ was part of her student placement with Great Place Falkirk.