The Carron Company is famous in Falkirk for many things, but few know about the sugar pans they produced for use on slave plantations.

Carron Co.

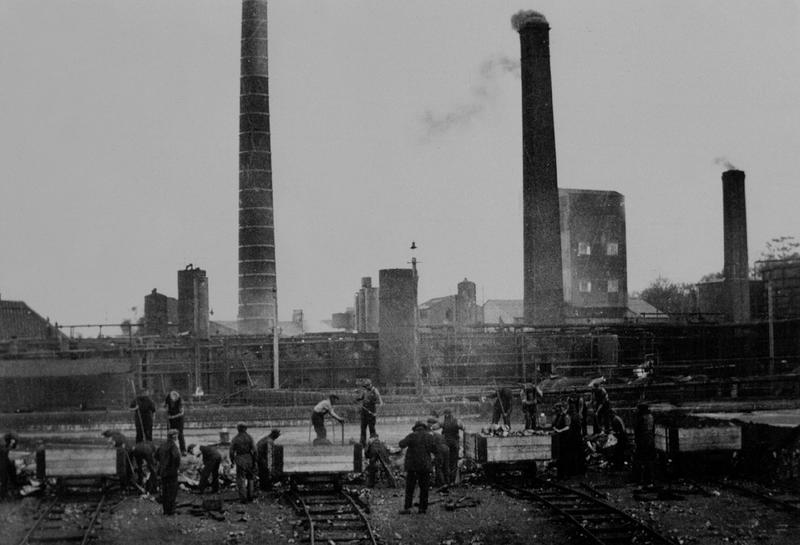

The Carron Co. Ironworks that was in operation from 1759-1982 is known for many great achievements. Its fame as the largest iron foundry in Europe, its contribution to the physical and economic growth of Falkirk, it’s feats of engineering, its popular manufactured goods such as the “Carronade” naval cannon and even an attempted visit by Robert Burns in 1787 are probably the most commonly cited successes (Watters 2005). The company’s indirect link to slavery in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, however, is probably less well known, but evident nonetheless in the form of one of its manufactured goods – the sugar boiling pan.

The Carron Co. sugar boiling pans were large iron pans used in the sugar plantations of the West Indies. They came in a variety of sizes and were considered by the company to be speciality items which would otherwise never have been made (Campbell 1961 105).

The Triangular Slave Trade

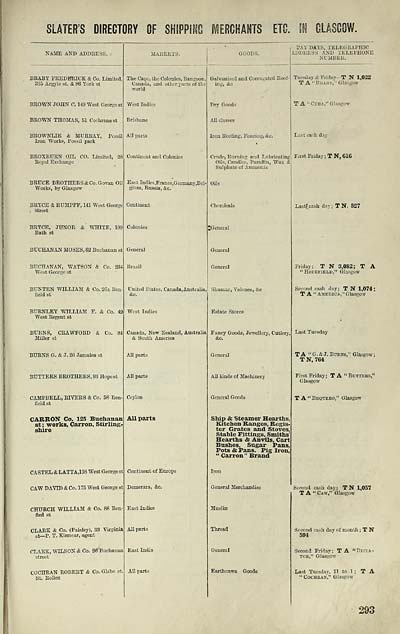

When the Carron Ironworks was founded in 1759, the European-controlled African slave trade was already well established. From the sixteenth century, the shipment of enslaved Africans from West Africa to the colonies in the West Indies and North America, to be utilised as slaves, was undertaken by the British, who set sail from English ports such as Liverpool, Bristol and London (Devine 2011 43). British involvement in this trade increased until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, by which time approximately 3.5 million enslaved Africans had been sent to the colonies (Devine 2011 43). While Scottish ports may not have been as active in the shipment of slaves, they were however considerably active and successful in the trade of goods to and from the plantations in America and the West Indies. Not only was tobacco, cotton, sugar, timber, and rice imported, but luxury items, household goods, plantation equipment, clothing and much more were also exported to the plantations (Devine 2011 46). The merchant houses of Glasgow operating out of Greenock and Port Glasgow eventually dominated tobacco imports and by 1765 controlled over 40% of Britain’s collective imports (Devine 2011 46). The establishment of Glasgow’s lucrative transatlantic trade routes was clear, and when the tobacco trade collapsed in 1775, the primary focus turned to the sugar colonies (Devine 2011, 48).

Sugar Pans

The Carron ironworks manufactured their first sugar pans in 1762, only three years after the company was founded (Campbell 1961 107). In those early days, the pans were almost exclusively sent to Glasgow merchants for distribution to the colonies due to the extensive trade network that had already been established.

In additional attempts to expand their global trade, the Carron Co. also sent some sugar pans to one of their partners in London (Thomas Roebuck) who attempted to sell them on to European markets (Campbell 1961 107). The commercial link to Glasgow was vital and transportation of goods from the Carron Co. to Glasgow was greatly improved in the 1770s with the building of the Forth & Clyde canal which was constructed for exactly that purpose (Bailey 2005). The transport of goods to London was also improved with the addition of the Carron Wharf and the Carron Company’s own shipping line – the Carron Line (Bailey 2005). Imports and exports via the Firth of Forth continued to expand and resulted in a larger port being built in Grangemouth, and the Carron Co., which was also expanding, moved its shipping there in 1850 (Bailey 2005).

Sugar Refinery

Once in the colonies these sugar pans were sent to plantations to be used in the sugar making process. The process started with the plantation of the sugar cane and the care of the crop until harvest. The harvested cane was then transported to a mill powered by man, wind or animal and then crushed between rollers to extract the sugar juice from the cane (Dunn 1973, 192). This juice was then carried along pipes to the boiling house where it was collected in a tank ready to be transferred along a series of 5 or more boiling pans (known as ‘coppers’) that decreased in size (Dunn 1973, 194). The pans were situated over burning fires and as the juice boiled, it was skimmed, reduced, and purified, before being ladled in to the next, smaller pan turning into a thicker browner liquid with every pan (Dunn 1973, 194). After being tempered with lime juice to promote granulation and knowing the crystallisation point (which was considered a highly skilled job), the final batch is then cooled (Dunn 1973, 194). The cooled sugar was then packed into clay pots and left to dry out for about a month, but after a few days, molasses was drained via holes in the bottom of the pots which was then sent to a distillery to make rum (Dunn 1973, 195). The remainder was semi-refined muscovado sugar which was dried in the sun before being packaged into hogsheads ready for export back to Britain (Dunn 1973, 196).

From the first manufactured pan in 1762, these pans continued to be produced consistently and profitably for 132 years throughout the changing supply and demand of other Carron Co. goods. They played a significant part in the early expansion of the Carron Company’s overseas markets and fortunes, and when the collapse of the sugar pan trade came in 1894, it also resulted in the slow decline of the company’s High Foundry (Campbell 1961, 302). The sugar pans may not be as well-known as the other Carron Co. products, but they were clearly a consistent and stable export. While their lack of recognition might simply be a case of out of sight, out of mind, their legacy lives on in the remnant plantations of the West Indies as a stark reminder of our colonial past.

By Lesley Ramsay, Great Place volunteer, Hidden Heritage: Industry and Empire project 2020.