Falkirk Community Trust has been collaborating with Sustrans on their wonderful Greenways project to bring some local heritage to life along the foreshore at Bo’ness. This is one of the stories from the project.

“During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, both shores of the Firth of Forth were studded with salt pans, and a big export trade was developed.”

Historian TJ Salmon (1913)

fields['text']) echo $section->fields['text']; ?>

The History

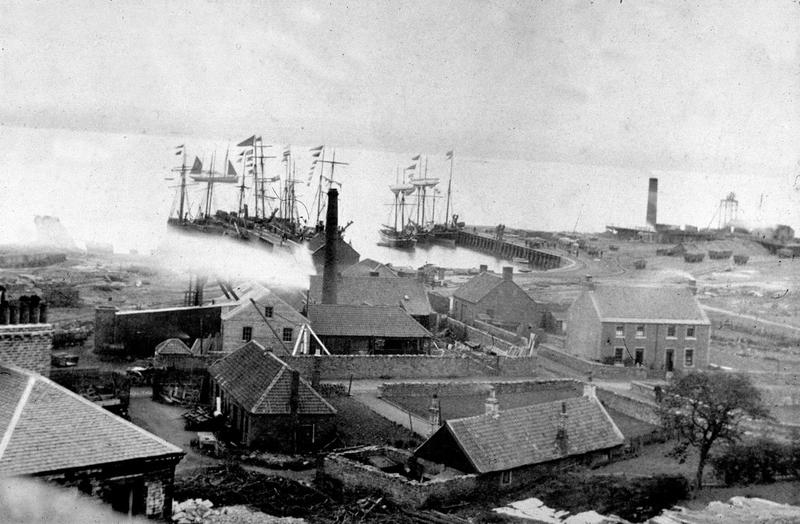

It was once called “white gold.” Sea salt was harvested in Scotland for hundreds of years – with the first salt pans being developed in the 12th century. By the 1790s, salt was Scotland’s third-largest export after wool and fish. Towns like Bo’ness set up pools close to coastlines to extract the commodity.

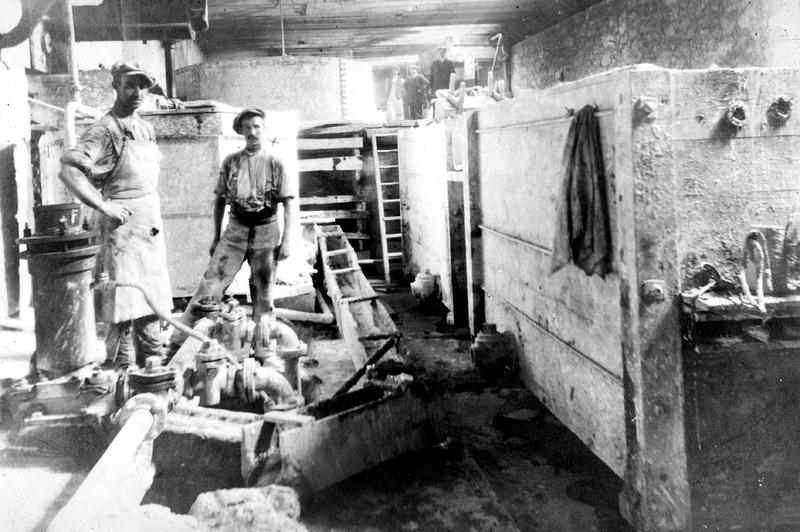

The pans worked like this: sea water would be pumped into troughs, which were then heated by coal (although peat and wood was originally used). The water was allowed to evaporate, in time leaving the salt.

Maps make references to salt pans at Kinneil (around Corbiehall); at Thirlestane and Grangepans (east of Bo’ness town centre); and at Bonhard pans and Caris pans (around Carriden). There has also been evidence of salt workings on the site of Dymock’s Buildings in the town centre. Sadly, there’s no sign of these works to see today. However, buildings associated with salt production still exist at Preston Island, by Culross, on the opposite side of the Firth of Forth.

Historian TJ Salmon, writing in Borrowstounness and District, published in 1913, said: “During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, both shores of the Firth of Forth were studded with salt pans, and a big export trade was developed.”

He notes the foreign demand was once so high that the price of salt was “ridiculously high” for local people to afford. Residents complained to the Privy Council, the executive body of the Scots Parliament. “An order was pronounced prohibiting the export of salt for three years,” he said. “The panmasters then complained that they could not live if the export were altogether stopped, and they offered to supply the natives what pan masters salt they required … if liberty was granted them to export the rest. This was agreed by the council.”

Saltmaking in the area continued to around 1889. The industry was killed off in Scotland due to a change in tax regime and a move to extract rock-salt from underground sites in Cheshire.

Salt Production in the Grangepans Area

Salmon also tells the history of salt production in Grangepans. He writes: “Saltmaking was an important industry in Grangepans. There were at one time thirteen pans in full swing. The sea water was originally pumped up to the pans by large pumps handled by several men or women, often with young people helping them, and it was a sight to see the pumps at work.”

“As the sea water was found too fresh, rock salt was, in later times, brought from Liverpool and Carrickfergus to strengthen the Grange salt. A ton of salt was carted regularly to Falkirk every week to supply the inhabitants of that town. People came from far and near to the Grange saltpans, as the local product was considered particularly good. The Government duty was heavy, and a Revenue officer was stationed at the pans. In consequence of the duty smuggling was very prevalent.”

“The salt was stored in large cellars or ‘girnels’ barred by strong doors, sealed up by a Custom-house officer, just as the bonded stores of the present day are sealed. It was not allowed to be taken out again until the duty was paid. The sea water and raw rock salt were full of mud and other impurities, and these were extracted by the additions of evil-smelling clotted blood to the boiling liquor. The albumen in the blood coagulated in the hot water, and floated up in a thick scum, which was skimmed off, leaving the solution perfectly clear. It was an interesting sight to watch the red blood spreading through the seething water, and coming to the surface in dirty brown or grey froth. The pans becoming unremunerative, gradually diminished in number in course of time, and the year 1889 saw the last of the saltmaking in this part of the Forth.”